|

Niobrarasaurus coleii

Remains of a plant eating dinosaur from the Smoky Hill

Chalk

Copyright © 2003-2014 by Mike Everhart

Last updated 03/08/2014

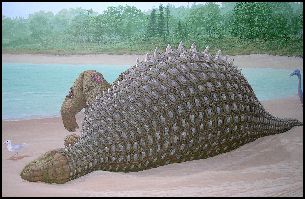

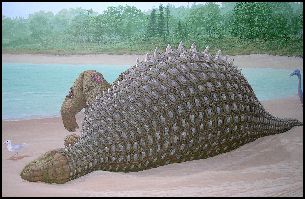

LEFT - Paleo-art by Kenneth

Carpenter, Denver Museum of Nature and Science, showing the type specimen of Niobrarasaurus

coleii floating in the Western Interior Sea. Note the Ichthyornis dispar

perched on the back of the dead dinosaur and the approaching shark. © Kenneth Carpenter,

used with permission. |

NEW DINOSAUR DISCOVERY - JUNE 2005 -

NEW DINOSAUR DISCOVERY - May, 2007 (SEE BELOW)

|

The Smoky Hill Chalk was deposited near the middle of the Western

Interior Sea, hundreds of miles from the nearest coast during the Late Cretaceous (about

87-82 mya). It is the last place I would ever expect to find a dinosaur. Yet the remains

of at least 8 (latest in May, 2007) dinosaurs have been discovered in the Kansas chalk.

Contrary to the picture at left, it is unlikely that they simply died along a beach and

were carried out to sea by the rising tide. Far more likely, some unlucky dinosaurs were

swept out to sea by rivers during flood stage or other similar scenarios. In some cases,

once the dead animal began to decompose in the warm water, enough gas was accumulated

within the abdomen to float the carcass. Prevailing winds and currents would have

eventually carried some of these bloated remains hundreds of miles from shore, and over

what is now western Kansas. Scavenged by sharks or just falling apart, the remains

eventually dropped to the sea floor and were preserved in the chalk along with the

skeletons of marine animals. |

|

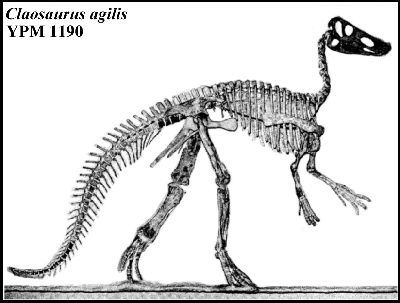

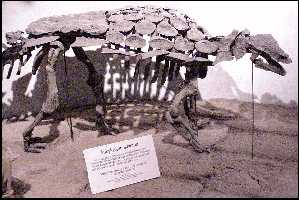

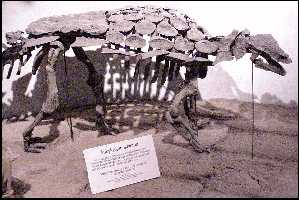

LEFT: Reconstructed skeleton of the Jurassic ankylosaur (Gargoyleosaurus parkpini)

in the Denver Museum of Science and Nature. Note scutes dermal covering the head and upper

body.) |

|

Several decades after Marsh's hadrosaur discovery, two sets of

fragmentary nodosaur remains (YPM 55419 (Fig. 7 and 7a) and YPM 1847 (Fig 1-6)) were

discovered in 1906 and 1908 by Charles Sternberg and his sons in southwestern Trego

County. Carpenter, et al. (1995) indicates that there is still some confusion regarding

these specimens. At first, Sternberg thought they were from some new kind of a

fossil turtle. He sent them to the Yale Peabody Museum where they were examined and later

described by G. R.

Wieland (1909), an expert on fossil turtles. The new dinosaur species was named Hierosaurus

sternbergi in Sternberg's honor. The figures at left were drawn for Wieland by

Mr. R. Weber and published in: Wieland, G. R., 1909. A new armored saurian from the

Niobrara. Cont. Peabody Museum, XIX:250-252. The best specimen of a

Kansas dinosaur, however, is a reasonably complete nodosaur (Ankylosauridae) found by an

oil field geologist in 1930. |

|

When is a "fossil turtle" a dinosaur? In 1899, C.

S. Parmenter described the cast of a fossil turtle from the Dakota Sandstone

(Cenomanian) of Cloud County. From a review of the photographs that were published

(LEFT - Click to enlarge), it is far more likely that the specimen represents the sacrum

of an ankylosaur such as Silvasaurus. Unfortunately, the specimen was subsequently

lost.

Parmenter, C. S. 1899. Fossil turtle cast from the

Dakota epoch. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 16:67. |

|

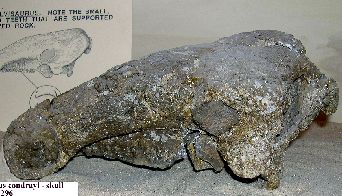

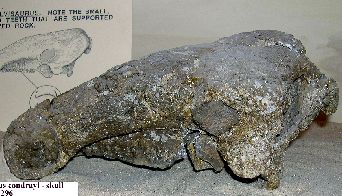

LEFT: The skull of the ankylosaur Silvisaurus condrayi

(KUVP 10296) from the Dakota Sandstone (middle Cenomanian) of Ottawa County, Kansas (north

of Salina, KS) in July, 1955. This is the most complete skull of a dinosaur ever

found in Kansas. It was described and named by T.H. Eaton, Jr. in 1960. RIGHT:

The partial sacrum of S. condrayi. The incomplete skeleton represents the

earliest known remains of a dinosaur in Kansas. |

|

A brief history of Niobrarasaurus coleii:

In February, 1930,Virgil B. Cole, a geologist doing surface mapping in western

Kansas for Gulf Oil , found the remains of a 'baby dinosaur' in southeastern Gove County

(roughly 20 miles or so south of Quinter). A letter

written by Cole to Dr. M. G. Mehl at the University of Missouri - Columbia described

the discovery and indicated that he was shipping it (300 pounds of bones and plaster) to

Missouri. Cole had been a student of Mehl and received his Master's degree from UM-C in

1923). The letter and some of Cole's field notes were retained with the specimen.

|

Cole's field notes provide reasonably accurate drawings of the

position the the right hind limb of Niobrarasaurus. LEFT:

Shows two views of the right tibia and fibula, along with several of the toes. Cole's

notes indicate: "Position the bones were found" and "Same bones."

Measurement of the lower right limb as found was 21 inches. RIGHT: Drawing shows the

right right front limb, with several scutes near the right elbow. The upper end of the

humerus is 9 inches wide, while the lower end is 6¼ inches wide. The humerus is 14½

inches long. His notes read: "This is somewhat out of proportion as the upper bone

should be larger. I thot (sic) it was paddle bone of a plesiosaur before. I dug out

the foot on the reverse side. All the bones found on both sides are in plaster

casts." Cole's field notes were recently published in their entirety: Cole,

V. B. 2007. Field

notes regarding the 1930 discovery of the type specimen of Niobrarasaurus coleii, Gove County, Kansas. Kansas

Academy of Science, Transactions 110(1/2): 132-134. |

|

From his letter and field notes, it is apparent that Cole initially thought the

remains were those of a plesiosaur. However, after excavating the fairly complete,

articulated hind limb, he realized that it was a dinosaur. It appears from what he wrote

that he was apparently somewhat disappointed at first that it wasn't a plesiosaur, but was

proud of his discovery throughout the rest of his life (Walters, 1986).

After receiving the specimen from Cole and removing it from the plaster that had been

poured directly on the bones, Mehl described the remains in an abstract for a GSA meeting

in 1931, and followed with a paper, naming it Hierosaurus coleii in honor of Virgil

Cole:

Mehl, M. G., 1931. Aquatic dinosaur from the Niobrara of western

Kansas. Bull. Geol. Soc. Amer. 42 326-327.

*Mehl, M. G., 1936. Hierosaurus coleii: a new aquatic dinosaur from the Niobrara

Cretaceous of Kansas. Denison Univ. Bull. Jour. Sci. Lab. 31 1-20, 3 pls. |

An (unpublished) note from Virgil

Cole that I found with the specimen in December, 2002, carries a bit more information,

some of it confusing: "Hierosaurus coleii more pieces picked up after the

rains June 8, 1935, Trego Co. Kan. Horizon 122' up in Niobrara Chalk V. B. Cole."

This is important since Cole had originally placed the specimen some 190' above

the base of the chalk.. somewhat higher (and younger) than I determined found the chalk to

be in the vicinity of the type locality. The original locality given by Cole is in Gove

County, but is also close to the county line between Gove and Trego counties to the east

of the locality.

After that, the specimen more or less sat unnoticed in the University of Missouri-Columbia

until the mid-1990s when the type material was re-examined. Because the original type

specimen of Hierosaurus "was based on indeterminate material and is thus

rendered a nomen dubium" and because MU 650 VP "possesses features that are

unique among ankylosaurs," Carpenter, et al. (1995, page 279) believed that it

constituted "the holotype to a new genus, Niobrarasaurus coleii."

| Carpenter, K., D. Dilkes, and D. B. Weishampel, 1995. The

dinosaurs of the Niobrara Chalk Formation (upper Cretaceous, Kansas), Journal of

Vertebrate Paleontology 15(2):275-297. |

In October, 2000, Shawn Hamm became the fifth person to find dinosaur remains

in the Smoky Hill Chalk (after O. C. Marsh, Charles Sternberg(2), Virgil Cole and J. D. Stewart (KUVP

25150)). In that case, it was the right radius and ulna (lower front limb) from a young

nodosaur which I was able to identify by comparison with Figures 10 and 12 in Carpenter,

et al., (1995). In early 2001, when Shawn Hamm and I submitted an abstract to the SVP for

a poster (Bozeman, 2001, see below), I decided that we needed to compare the two bones

that Shawn had found with those of the type specimen (MU 650 VP). So after contacting the

Department of Geological Sciences at the University of Missouri at Columbia in March,

2001, I requested the right radius and ulna be sent on loan to the Sternberg Museum.

Click here for a map showing the approximate

localities of nodosaurs found in the Smoky Hill Chalk of western Kansas.

|

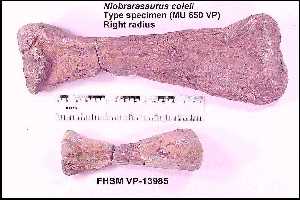

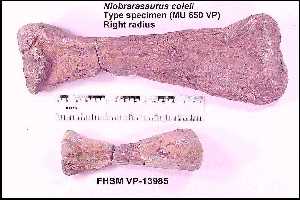

The right radius and ulna of the juvenile remains found by Shawn

Hamm (FHSM VP-13985) compared with those of the adult(?) holotype specimen of Niobrarasaurus

coleii (MU 650 VP). |

|

Even though VP-13985 represents a much younger individual, they appear to very

similar in shape to the type of Niobrarasaurus. The bones had apparently been

ripped off the floating carcass of a nodosaur by large shark, swallowed and partially

digested, then regurgitated. What appears to be long

bite marks are visible on the distal end of the radius, and is possibly the result of

the tips of two or more of the sharks teeth dragging across the bone as the shark tried to

tear the limb from the carcass.

In the August, 2002, when I returned the type material (MU 650 VP) to the University

of Missouri, I asked my contact there if it might be possible that the entire specimen

could be transferred to the Sternberg Museum for exhibit. He told me that he would check

with the administration and the answer was a very gracious "yes." Last December

(2002), I arranged to stop by the University of Missouri-Colombia on our way back to

Kansas from Chicago and pick up the specimen. The significance here may be that the

Sternberg now has the ONLY two known specimens of this genus / species. I am very

grateful to the University of Missouri-Columbia and the Department of Geological Sciences

for making this transfer possible.

|

On May 1, 2003, a 2 PM media conference was arranged at the

Sternberg Museum to announce the acquisition of the type specimen of Niobrarasaurus

coleii (now FHSM VP-14855). I spent the morning arranging a display of the bones

of Niobrarasaurus on a piece of dark blue cloth and talking to reporters and

photographers who arrived early. It was possibly the first time that the specimen

had been laid out completely since it was first prepared, and certainly the first time

that it had been photographed so extensively. On May 3, after most of the news stories had

played out, I took a group of amateur paleontologists into the field. By

coincidence, we were hunting fossils in the same section (square mile) that had produced

the bones of Niobrarasaurus in 1930. The locality also happens to be one of my

favorite areas of the chalk and one for which we had access from the property owners. And

there begins the rest of this strange and wonderful story... |

May 3, 2003: The morning promised a pretty nice day for fossil hunting. It was

cool and cloudy, with just a bit too much wind at times. The five us scattered quickly

across the shallow valley just south of the Smoky Hill River. We were all carrying radios

but, surprisingly, there was little of chatter that we usually had when we were having

good luck finding fossils. My day started pretty well, finding a very nice, though

partially digested mosasaur axis vertebra. and ended

with the discovery of my first Martinichthys

rostrum since 1996. About 5:00 PM, just as I began the walk back to the van to leave

for the day, Tom Caggiano called me on the radio and told me he

had found some unusual bones. After kidding around about him finding a "Bovinasaurus"

(cow bones) in the pasture that he was walking through, I asked him what they were. He

said that he didn't know. When I met up with him, he showed me four bones, bleached

gray-white by exposure to the Kansas sun. I recognized them immediately as dinosaur foot

bones, just like the ones I had arranged in the Niobrarasaurus exhibit at the

Sternberg two days earlier. Great! I thought, Tom had discovered another Smoky Hill

Chalk dinosaur... only the sixth person to ever do so. We were both excited as we

walked back to the site where he had found the bones.

Tom had seen the terminal phalanx lying

on the side wall of a 7 foot deep gully that he was walking through, at about eye

level. When he had climbed up to see where it came from, he found the three

metacarpals lying close together, near the edge. As I examined the bones again, I noticed

that all three of the metacarpals still had bits of white plaster still clinging to

them. I realized at that point, that this wasn't a "new" dinosaur at all,

but rather the lingering remains of Cole's original Niobrarasaurus discovery! Tom

had chanced upon the type locality of the type specimen.

|

To me, Tom's discovery was even more important because it

accurately located the type specimen stratigraphically below Marker Unit 3 (Upper

Coniacian (86 mya), about 85 feet above the contact with the Fort Hays Limestone) and

verified what I had concluded when I first started looking at the occurrence of dinosaurs

in the Kansas chalk. Of course, it also added four of the missing bones of the right front

foot that may have been noted by Cole in the last

line of the first page of his letter to Mehl. As best I could determine from his

letter, Cole had poured plaster on everything (literally, directly on the bones), and then

unintentionally covered the right front foot with rock and dirt as he dug around to remove

the larger bones of the right limb. The plaster cap protected the bones and held them

together for many years before it finally weathered away. There is little doubt that

it was the plaster coating that enabled them to survive in place for 73 years until they

were re-discovered. |

We got the rest of the group together and did a thorough search of the area.

Although we found plaster still clinging to some inoceramid shell fragments, we were

unable to locate any additional remains of the Niobrarasaurus. Cole's field notes

did not indicate how many bones were originally found in the right foot... I would suspect

that several other smaller toe bones had already been washed away. Another heavy

rain and the four "strange" bones found by Tom Caggiano could have suffered the

same fate.

And there you have the rest of the story of Niobrarasaurus coleii....

newly arrived back in Kansas where he had spent most of the last 86 million years, and

re-united with a few more of the original bones.

|

At left, Tom holds the four additional Niobrarasaurus

bones that he found on May 3, 2003. At right is a photograph of the newly discovered

material with the lower limb bones of the right front leg. Note that the white patches on

the metacarpals are plaster, not chalk. A larger photograph of the lower right front limb is here. A photograph

of a cast of the right REAR foot currently on display as an exhibit in the Sternberg Museum is here. |

|

The photos below were taken at the Niobrarasaurus site on May 31,

2003. The bones were discovered in the foreground of the picture at right (below) and

occurred stratigraphically below Hattin's (1982) Marker Unit 3.

|

LEFT: The series of vertebrae of the tail of Niobrarasaurus

coleii (FHSM VP-14855) is nearly complete. RIGHT: Three caudal

vertebrae from FHSM VP-14855 in left lateral and dorsal view. (Scale = cm) |

|

|

After the transfer of the specimen and the re-discovery of the

type locality (and additional remains), the various fragments of the skull were reexamined

by Dr. Kenneth Carpenter (Denver Museum of Nature and Science and reconstructed into a

hypothetical skull. (See Carpenter and Everhart, 2007) |

|

----------------------------- Abstract:

2001, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 21(suppl. to 3):58A. Bozeman, MT

----------------------

NOTES ON THE OCCURRENCE OF NODOSAURS (ANKYLOSAURIDAE) IN THE SMOKY HILL CHALK (UPPER

CRETACEOUS) OF WESTERN KANSAS

HAMM, Shawn A., Department of Geology, Wichita State

University, 1845 Fairmount, Wichita, KS, 67260; EVERHART, Michael J., Sternberg Museum of

Natural History, Fort Hays State University, Hays, KS, 67601.

The Smoky Hill Chalk Member of the Niobrara Chalk was deposited near the middle

of the Western Interior Sea, several hundred miles from the nearest land, in late

Coniacian through early Campanian time. The chalk is well known for its excellent

preservation of late Cretaceous fish, marine reptiles, pteranodons and toothed birds.

Although terrestrial vertebrate remains are rare, the chalk has produced the best

assemblage of Coniacian-Santonian nodosaur specimens presently known from North America.

The occurrence of terrestrial animals in this marine unit is most likely due to a

"bloat and float" scenario where the animal was washed out to sea, carried some

distance by currents and then sank. Jaws, skulls, neck and tail vertebrae, and distal limb

elements are the first parts of a floating carcass to fall off or be detached by

scavengers. Here we report on the discovery of an isolated radius and ulna of a nodosaurid

dinosaur from the Smoky Hill Chalk Member in Lane County, Kansas. The bones were found

near the base of Marker Unit 8 (middle Santonian), within the biostratigraphic zone of Clioscaphites

vermiformis and C. choteauensis. Bite

marks and the partially digested appearance of the proximal and distal ends of the bones

suggest scavenging by the lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli. The radius

and ulna are about half the length of the comparable bones of the holotype of Niobrarasaurus

coleii (MU 650 VP), and indicate a juvenile animal that was about 3 m long. Besides MU

650 VP, only three other sets of nodosaur remains had been previously documented from the

chalk. These include the holotype of Hierosaurus sternbergii

(YPM 1847); a pair of scutes (YPM 55419); and a partial skeleton (KUVP 25150). MU 650

VP, YPM 1847, and YPM 55419 are late Coniacian in age while KUVP 25150 is middle

Santonian. From a comparison with the holotype, the new specimen has been tentatively

identified as Niobrarasaurus coleii.

Click here for a map showing the

approximate localities of nodosaurs found in the Smoky Hill Chalk of western Kansas |

A new nodosaur specimen

(Dinosauria: Nodosauridae) from the Smoky Hill Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) of western Kansas.

Everhart, M. J. and S. A. Hamm. 2005. A new nodosaur specimen

(Dinosauria: Nodosauridae) from the Smoky Hill Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) of western Kansas.

Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 108(1/2): 15-21.

The right ulna

and radius of a small nodosaur were recovered from the Smoky Hill Chalk Member (Upper

Santonian) of the Niobrara Formation in October, 2000. Based on the similarity of the

specimen in comparison with the holotype of Niobrarasaurus coleii, and the

relatively small size of the remains, the bones are considered to be those of a juvenile N.

coleii. The presence of two parallel scratch marks on the distal shaft of the radius,

and the partially digested appearance of the proximal and distal ends of both bones,

suggest that the lower limb had been detached from the carcass as the result of

scavenging, most likely by the large lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli.

Although the remains of terrestrial vertebrates are not unknown from sediments deposited

in the Late Cretaceous Western Interior Sea, additional discoveries are infrequent and

valuable sources of information regarding the terrestrial fauna of the time. |

|

LEFT: In June, 2005, I was present when the 6th dinosaur specimen

ever found in the Smoky Hill Chalk was discovered by my friend, Keith Ewell. The specimen

consisted of 9 caudal vertebrae that had apparently been detached and swallowed by a large

shark (again most likely Cretoxyrhina). The specimen was donated to the

Sternberg Museum and was the subject of a recent paper (Everhart and Ewell, 2005). See the web page here. According to Ken Carpenter, the long,

slender neural spines are distinctive to hadrosaurs. (Scale = cm) |

|

LEFT: A juvenile nodosaur caudal vertebra (FHSM VP-16385) that was

found by Keith Ewell in 2004 in Trego County (Smoky Hill Chalk - Upper Coniacian). The

vertebra appears to be partially digested, most likely by a large shark. Approximately

life-sized. Keith is now the only person in 134 years to ever find the remains of

two dinosaurs in the Smoky Hill Chalk. (um.... well, see the most recent discovery

below.... There have been as many dinosaur specimens found in the Smoky Hill Chalk in the

last 10 years as in the previous 130!) |

|

EIGHTH DINOSAUR SPECIMEN FOUND IN THE SMOKY HILL CHALK (FHSM

VP-17229) LEFT: Over the Memorial Day weekend in 2007, Laura and Scott

Garrett were prospecting for fossils in the lower Smoky Hill Chalk (below Hattin's Marker

Unit 3 - Late Coniacian) of southwestern Trego County. Laura found an isolated anterior

caudal vertebra (near the base of the tail) from what appears to be a large ankylosaur,

most likely Niobrarasaurus coleii. Note that this vertebra is very

similar to, but much larger than, the one collected by Keith Ewell in 2004 (above). Laura

becomes the first woman (and only the 7th person) to ever collect dinosaur remains from

the Smoky Hill Chalk. The Garretts generously donated the specimen to the Sternberg Museum

of Natural History (VP-17229). The specimen comes from about 6 miles south of the site

where VP-16385 was collected in 2004, and from about 5 miles east of where the type

specimen of Niobrarasaurus coleii (VP- 14855) was collected in 1930. All are Late

Coniacian in age. |

Suggested references:

Carpenter, K., D. Dilkes, and D. B. Weishampel. 1995. The dinosaurs of the Niobrara

Chalk Formation (upper Cretaceous, Kansas), Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 15(2):

275-297.

Carpenter, K. and Everhart, M. J. 2007. Skull of the ankylosaur Niobrarasaurus

coleii (Ankylosauria: Nodosauridae) from the Smoky Hill Chalk (Coniacian) of western

Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions, 110(1/2): 1-9.

Cole, V. B. 2007.

Field

notes regarding the 1930 discovery of the type specimen of Niobrarasaurus coleii, Gove County, Kansas. Kansas

Academy of Science, Transactions 110(1/2): 132-134.

Eaton, T. H. Jr., 1960. A new armored dinosaur from the Cretaceous of Kansas.

University Kansas Paleontology Contri. 8:1-14, 2 fig. (Silvisaurus)

Everhart, M. J. 2004. Notice of the transfer of the holotype specimen of Niobrarasaurus

coleii (Ankylosauria; Nodosauridae) to the Sternberg Museum of Natural History. Kansas

Academy of Science, Transactions 107(3-4): 173-174.

Everhart, M. J. and Ewell, K. 2006. Shark-bitten dinosaur (Hadrosauridae)

vertebrae from the Niobrara Chalk (Upper Coniacian) of western Kansas. Kansas Academy

of Science, Transactions, 109 (1-2):27-35.

Everhart, M. J. and S. A. Hamm. 2005. A new nodosaur specimen

(Dinosauria: Nodosauridae) from the Smoky Hill Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) of western Kansas.

Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 108(1/2): 15-21.

Liggett, G. A., 2001. Dinosaurs to Dung Beetles: Expeditions

through time - A guide to the Sternberg Museum of Natural History. Sternberg Museum of

Natural History, Hays, KS. 127 p.

Liggett, G. A. 2005. A review of the dinosaurs from Kansas. Kansas

Academy of Science. Transactions 108(1/2): 1-14.

Hamm, S. A. and M. J. Everhart. 2001. Notes on the occurrence of nodosaurs

(Ankylosauridae) in the Smoky Hill Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) of western Kansas. Journal of

Vertebrate Paleontology 21(suppl. to 3): 58A.

Hattin, D. E. 1982. Stratigraphy and depositional environment of the Smoky Hill

Chalk Member, Niobrara Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) of the type area, western Kansas. Kansas

Geological Survey Bulletin 225, 108 pp.

*Marsh, O. C. 1872. Notice of a new species of Hadrosaurus.

American Journal of Science, Series 3, 16: 301.

Marsh,

O.C. 1890. Additional characters of the Ceratopsidae, with

notice of new Cretaceous dinosaurs. American Journal of Science, Series 3, 39:

418-426, with pls. v-vii.

Mehl, M. G. 1931. Aquatic dinosaur from the Niobrara of western Kansas.

Bulletin of the Geological Society of America 42: 326-327.

*Mehl, M. G. 1936. Hierosaurus coleii: a new aquatic dinosaur from the

Niobrara Cretaceous of Kansas. Denison University Bulletin, Journal of the Scientific

Laboratory 31: 1-20, 3 pls.

Shimada, K. 1997. Paleoecological relationships of the late Cretaceous

lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli (Agassiz). Journal of Paleontology. 71(5):

926-933.

Parmenter, C. S. 1899. Fossil turtle cast from the

Dakota epoch. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 16: 67.

Sternberg, C. H. 1909. An armored dinosaur from the

Kansas chalk. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 22: 257-258.

Stewart, J. D. 1990. Niobrara Formation vertebrate stratigraphy, pages 19-30, In

Bennett, S. C. (ed.), Niobrara Chalk Excursion Guidebook, The University of Kansas Museum

of Natural History and the Kansas Geological Survey.

Varricchio, D. J. 2001. Gut contents from a Cretaceous tyrannosaurid;

Implications for theropod dinosaur digestive tracts. Journal of Paleontology

75(2):401-406.

Walters, R. F. 1986. Memorial: Virgil Bedford Cole (1897-1984). AAPG

Bulletin, 70(2):208-209.

Wieland, G. R. 1909. An armored saurian. Contrib. American Journal of Science

27: 250-252. (March)

Wieland, G. R. 1909. A new armored saurian from the Niobrara. Contributions to

the Peabody Museum, XIX: 250-252

Wieland, G. R. 1911. Notes on the armored Dinosauria. American Journal of

Science 31: 112-124.

* - Reference material provided by E. Manning

Credits: The suggestions and corrections to this page provided by Earl

Manning are gratefully acknowledged.