| October 7, 1904.]

SCIENCE

465

DISCUSSION AND CORRESPONDENCE.

A RECENT PALEONTOLOGICAL INDUCTION.

THE concept of

arboreal 'horses' already thrice discussed in the current volume of SCIENCE, or even

concepts of fabled Pegasi, are, from a philosophical standpoint, rational and legitimate

products of human

466

SCIENCE

N.S. Vol. XX, No. 510.

consciousness. Nevertheless, the probability of such

conceptions having had real counterparts in the material world is

absolutely nil, so far as experience shows, and for like reason we can ascribe only a

mythical existence in times past to warm-blooded reptiles, feathered reptiles, or reptiles

possessing so eminently bird-like a characteristic as the gizzard.

It is, therefore, surprising to find a writer in SCIENCE (No. 501, p. 185) advancing the anomalous conception of

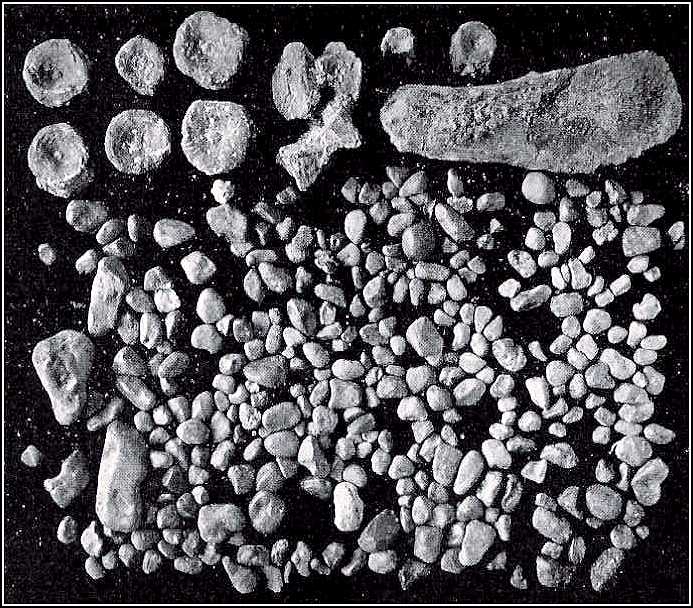

reptiles with organs corresponding to the avian gizzard. The solitary fact upon which Mr.

Barnum Brown bases his conclusion is the discovery, in a number of instances, of

small-sized silicious [sic] pebbles in association with plesiosaur skeletons from the

western Cretaceous. Certain corollary assumptions, apparently accepted as axiomatic

by Mr. Brown, but nevertheless debatable, may be stated as follows:

(1) These' stomach stones' were contained within the

alimentary canal prior to the death of the creatures, and not accidentally deposited upon

or with their remains. (2) The stones were intentionally swallowed, and not taken

promiscuously with other fare, as might happen in bottom-feeding. (3) They served as a

mechanical aid to digestion through the intervention of a supposititious gizzard-like

organ. (4) Thin-shelled prey like cephalopods could not have been crushed upon one another

without the admixture of a judicious quantity of' stomach stones. (5) The non-occurrence

of such stones amongst European reptiles proves only that the latter' had no stomach' for

them, not that they were gizzardless. (6) The history of the gizzard (horresco referens)

shows that it was developed first amongst cold-blooded vertebrates, then lost by them, and

afterwards independently acquired by birds. Incidentally it appears that plesiosaurs

possessed the most highly specialized digestive apparatus known amongst reptiles, ancient

or modern.

For our part, begging pardon of Mr. Brown, we are

willing to consign to birds the exclusive enjoyment of gizzards and feathers. A cogent

reason for suspending judgment as to the function of 'stomach stones' is found in their

limited distribution. Before asking us to believe that all plesiosaurs had 'gizzard- like

arrangements' [sic], let it be shown that all plesiosaurs and related reptiles had the

habit of gorging themselves with foreign matter to the extent asserted of American

species, and let no doubt remain that these pebbles are not of adventitious origin.

C. R. EASTMAN.

HARVARD UNIVERSITY. |