|

A Field Guide to the Smoky Hill Chalk

Part 1: Invertebrates

Copyright © 2000-2013 by Mike Everhart

Last revised 11/11/2013

LEFT: A beautiful specimen of Uintacrinus

socialis crinoids collected by Chuck Bonner and on display in the Keystone Gallery

(about three feet across) |

INVERTEBRATES: Besides being mostly composed of microscopic

fossils itself (coccolithophores and coccoliths of marine algae), the Smoky Hill Chalk

contains the remains of many invertebrates (animals without backbones) including clams,

crinoids and cephalopods (squids and ammonites). Other kinds of invertebrates that are

found, but not well represented in the fossil record include sponges, cirripids, annelid

worms and, rarely, crustaceans.

|

The Smoky Hill Chalk was deposited near the center of the

Western Interior Sea during Late Cretaceous time (Late Coniacian-Early

Campanian; 87-82 mya). This map shows the

extent of the seaway about 90 million years ago. (Map is part of the exhibits at the

University of Nebraska State Museum, Lincoln, NE.) Although the Smoky Hill Chalk has been

a excellent source of well preserved vertebrate remains, the preservation of

invertebrates, except inoceramid clams. oysters and rudists, is generally poor because

much of the shell material (aragonite) was dissolved prior to fossilization. This includes

the nacre of most shells and the shiny coating of fossil pearls. |

Inoceramids: Some species of clams (bivalves) grew to

giant size in the late Cretaceous, attaining diameters of four feet or more. In cross

section, these shells are composed of prismatic (calcitic)

crystals. The inner, nacreous (Mother of Pearl) layer of the shell was usually

dissolved during fossilization and the outer portion is usually covered with colonies of

oysters and other invertebrates. Pearls are occasionally found

pressed into the Inoceramid shell. According to Sowerby 1823, Inoceramus

means "fibrous shell," describing the prisms that are visible on shell

fragments. Inoceramus cuvieri was the first species of Inoceramus

that was formally described.

|

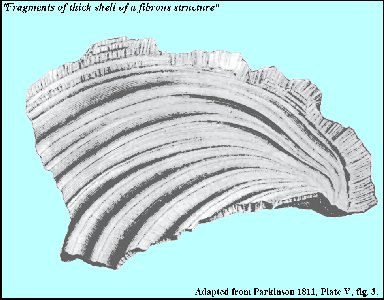

James Parkinson (1811b) wrote one

of the first descriptions of an inoceramid shell:

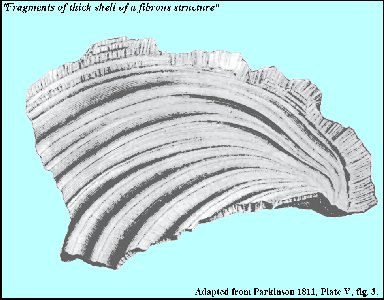

"Fragments of thick shell of a fibrous structure: The doubts expressed respecting the nature of this

shell, and the observations made with regard

to it, offer another strong point of agreement between the shells of the

two strata. The shell here alluded to is most probably

that represented Org. Rem. vol.

III. pl. V.-fig. 3; the structure of which agrees exactly with that

mentioned as found in the French stratum of- chalk. That shell is however

described as being of a tubular form; it is therefore right to observe,

that fossil pinnae do

sometimes

possess

this peculiar structure."

LEFT:

Figure 3 from Plate V in Parkinson's Organic Remains of a Former World

(1811a).

Parkinson, J. 1811a.

Organic Remains of a Former World – An Examination of the Mineralized

Remains of the Vegetables and Animals of the Antediluvian World. Vol III,

Whittingham and Roland, London, i-xv, 479 pp., plates I-XII, index.

Parkinson,

J. 1811b.

Observations on some of the strata in the neighborhood of

London

, and on the fossil remains contained in them. Transactions of the

Geological Society of

London

1(XIV):324-354. |

|

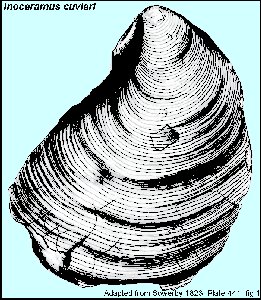

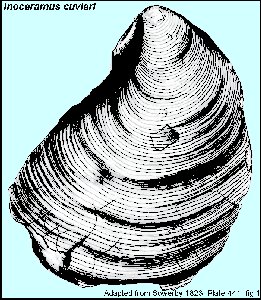

LEFT: A drawing of Inoceramus cuvieri Sowerby

(1814) from Great Britain as figured in Sowerby and Sowerby (1823). I.

cuvieri is fairly common in the Greenhorn and Carlile (Turonian)

formations in Kansas, but I had never paid much attention to it. In late

2011, I needed the citation for the name given by Sowerby and discovered

that it wasn't really that easy to find. In fact the first citation that I

worked with was incredibly wrong. The citation pointed back to seven

volumes of a book written by Sowerby between 1812 and 1843 called "The mineral conchology of

Great Britain

, or colored figures and descriptions of those remains of testaceous

animals or shells, which have been preserved at various times and depths

in the Earth." ... After some searching, I found Inoceramus

cuvieri described and figured (left) in Volume 5, but the volume had

been published in 1823, not 1814. So I kept looking. The solution to the

mystery was found on page 457 of a paper published by James Sowerby in

1822:

Sowerby, J. 1822. On a fossil shell of a fibrous

structure, the fragments of which occur abundantly in the chalk strata and

in the flints accompanying it. Transactions of the Linnean Society of

London

XIII: 453-458. Plate XXV.

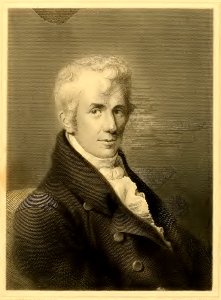

LEFT:

A note at the beginning of the paper states that it had been read orally

by (James Sowerby (1757-1822) before the meeting of the society on

November 1, 1814. There was no explanation of the delay in

publication. His son, James De Carle Sowerby (1787-1871)

continued the publication of the conchology books starting with Volume 5.

Volume 7 was never finished. |

|

|

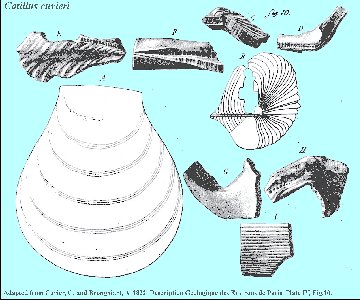

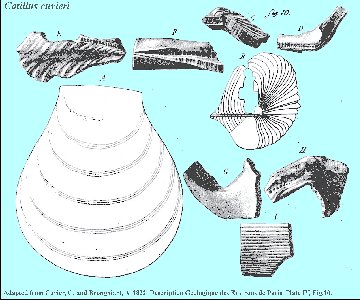

LEFT: It is worth noting that about the same time, Cuvier

described a similar species from France, and indicating that it differed

from Inoceramus in some ways, but also credited the work of Sowerby

and James Parkinson (Cuvier, G. and Brongniart, A. 1822. Description

Géologique des Environs de Paris):

"Fig.10,

A, E, F, G, H,

I.

Catillus cuvieri, A. BR. (p.15) Inoceramus cuvieri, SOW., PARK.

The

name Inoceramus has been given

to shells which seem to me show so numerous and striking differences that

I could not decide to keep them together, breaking the law I imposed

myself to bring no change in the shells division (family), such as it had

been established by the specialists. One has just to compare the fossil

shells that I unite here under the name of Catillus

with Inoceramus, fig.11 and 12,

pl.VI, to be stricken by this difference. The species of both these genera

are found in the chalk, but they are located in very distant strata.

It

has seemed logical for me to keep the name Inoceramus

for the gender composed of the

shells that M. Parkinson made known and drew under this name in the first

volume of the Transactions of Geol. Soc. of London., that M. Sowerby

established and presented under this same name et the Linnaean Soc. of

London in 1814, of which figures he just published in plates 305 and

306 in

Conchology, and I have preferred give a new name to the species for

which I see no description nor precise figure anywhere.

I

haven't yet seen an entire individual of this species, so that the gender

itself is difficult to characterize; but with the help of hinge fragments

from various collections, with the figures published by MM. Parkinson and

Mantell, one can succeed in characterizing satisfactorily this gender so

as it can be recognized by geologists, and give them a way to designate in

a uniform manner so remarkable a shell commonly found in the white chalk."

(Translation by Jean-Michel Benoit) |

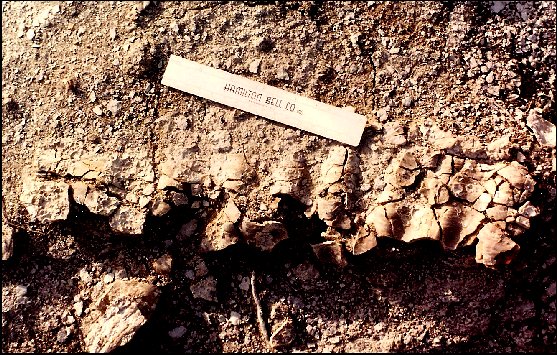

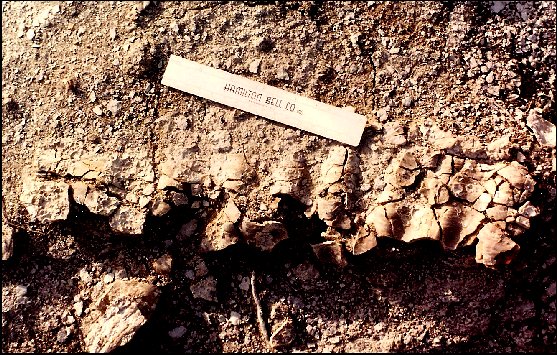

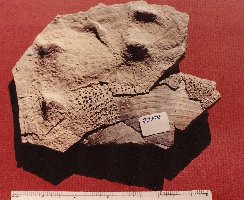

Volviceramus grandis (Late Coniacian)

| Volviceramus grandis: A common clam found in the lower

third (late Coniacian) of the chalk. The lower shells are thick and generally bowl shaped.

In many areas, the surface of the chalk is littered with thousands of fragments of this

shell, some of which may resemble bone in outward appearance. Examination

of the edge of the fragment will determine if it is bone (porous) or shell

(crystalline structure). |

|

LEFT: Volviceramus grandis - A common, large bivalve in

the lower Smoky Hill chalk. This lower valve measures 12 inches by 10 inches. Click here for a view of the other side of this

shell which is encrusted with Pseudoperna congesta oysters. RIGHT:

A juvenile V. grandis lower valve with attached P. congesta oysters.

This shell measures about 2.5 by 2.0 inches. The shell crushing shark, Ptychodus, most likely fed on shells that were about

this size. |

|

|

LEFT: A field photograph of a medium sized V. grandis

shell that was relatively uncrushed and shows the depth of the bowl shape. Specimen was found in the

lower chalk of Trego County RIGHT: A field photograph of a complete V.

grandis shell from the lower chalk of Trego County with the upper (right) valve still

in place, and completely covered with Pseudoperna congesta oysters. The

bottom of this specimen was also completely covered with oysters. |

|

Cladoceramus undulatoplicatus (Early Santonian)

|

Cladoceramus undulatoplicatus: A large fossil clam that

occurs in a limited zone about 1/3 of the way up from the base of the chalk

(above Marker Unit 7). This zone straddles the boundary between the

Coniacian and Santonian ages. The shell of Cladoceramus undulatoplicatus

is

characterized by deep ripples and it has been referred to as the "Snowshoe Clam." LEFT:

The broken edge of a large Cladoceramus undulatoplicatus eroding from the edge of

a gully in the lower Smoky Hill chalk. This specimen was associated with the

discovery of a Pteranodon sternbergi

skull. in 1996. RIGHT: Another large Cladoceramus undulatoplicatus eroding from

the lower Smoky Hill chalk. This specimen was associated with the

discovery of a Ptychodus mortoni specimen (FHSM VP-14785).

|

|

Platyceramus platinus (Latest Coniacian

through Early Campanian):

|

A very large clam shell that occurs throughout the chalk,

sometimes reaching more than four feet in diameter in Kansas. They are thought to be the largest

clams ever, reaching nearly 9 feet in length (3-4' width) in the Niobrara of

Colorado (see Kauffman, et al, 2007). As the name implies, these shells are

relatively flat and often very thin. While alive,

the interior sometimes served as shelter for schools of small fish which are occasionally

preserved inside as fossils pressed into the shell. LEFT: The

exhibit specimen of Platyceramus platinus (FHSM IP-532) at the Sternberg Museum.

This shell is about 3 ft. wide and 3.5 feet long. (Scale = 10 cm)

The latest publication on these giant clams is:

Kauffman, E.G., Harries, P.J., Meyer, C.,

Villamil, T., Arango, C. and Jaecks, G. 2007. Paleoecology of giant Inoceramidae (Platyceramus)

on a Santonian seafloor in Colorado. Journal of Paleontology

81(1):64-81. |

|

LEFT: Part of a large Platyceramus platinus eroding from

the middle of the Smoky Hill Chalk. (Scale = 6 in / 15 cm). There has been some

controversy regarding the orientation of these clams as they sat on the sea bottom because

oysters (Pseudoperna congesta) have been found on both sides. Stewart (1990)

suggested that they sat upright, something like modern giant clams are found in modern

coral reefs. Others (Kauffman, et al., 2007) indicate that they usually occurred in a

recumbent mode, with the left valve on the sea floor. Since the shells are somewhat bowl

shaped, this would allow oysters to colonize the lower portion around the edges.

Otherwise, the shell could have been colonized after it had died and been turned

over (although it is unknown "how" it would have been turned

over).

RIGHT: My concept of a giant (> 1m) Platyceramus

platinus resting on the sea floor with a rather large area of the rim of the lower

shell exposed above the sediment... a great location for oysters looking for a home. |

|

|

LEFT: A very large P. platinus shell eroding from the

lower chalk of Trego County. The shell is almost completely covered with Pseudoperna

congesta oysters. The shell is about 1 m (39 in.) across. RIGHT:

Platyceramus platinus shells were so large that they provided shelter for schools

of small fish. Sometimes the fish were trapped inside the clam's shell when it died.

This picture shows skeletal fragments of small fish that were preserved inside a Platyceramus

platinus shell from the Smoky Hill Chalk. |

|

| How to collect a giant clam shell by Charles H.

Sternberg (pp. 24-25, Sternberg, C.H. 1917. Hunting Dinosaurs in the

Badlands of the Red Deer River, Alberta, Canada. Published by the

author, San Diego, Calif., 261 pp.)

Here,

too, in the [AMNH] Invertebrate

Department, is the great Inoceramus

shell 3'4"x3'7" in size. The second shell of these huge

dimensions I sent to Tübingen University. Although they strew the rocks

of the Kansas chalk in great numbers, they are always broken into small

pieces, and these are scattered by the winds of heaven. It seems

impossible to preserve

them. But George [his son] and I learned the secret, and after

finding a shell with· lips or hinge exposed, we carefully removed the

loose chalk above it, then put a frame of two by four lumber around it, in

which we poured plaster. On hardening thus stuck securely to the shattered

shell, holding the fragments in place. Then we dug beneath and turned over

the panel, and in the shop removed the chalk, leaving one side of the

shell exposed in the solid plaster. |

Pseudoperna congesta (Oysters)

) |

Small bivalve shells, similar to the oysters found in the ocean

today, covered any solid object that they could attach to. Inoceramid clam shells,

rudists, driftwood and the skeletons of marine reptiles served as homes for oysters and

other invertebrates in the inland sea. Sometimes there were 3 or 4 layers as succeeding

generations built up on the same shell. The lower, or right shell of the oyster is

attached to the substrate. The other shell was free to open and close. The species found

most often is called Pseudoperna congesta (Conrad, in Nicollet, 1843, p. 169): "*Conrad's

description of the Ostrea congesta: Elongated; upper valve flat; lower valve

venticose, irregular; the umbo truncated by a mark of adhesion; resembles a little gryphea

vomer of Morton." LEFT: Several small oysters on Inoceramid

fragments and an unusual, unattached oyster shell (upper right). Exogyra is a very rare and recently discovered, but

unnamed species of oyster in the lower Smoky Hill Chalk. (Hattin, 1995

|

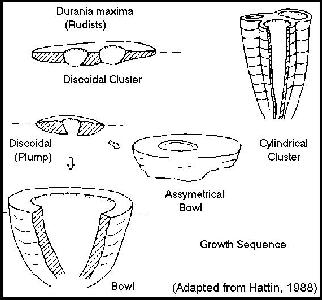

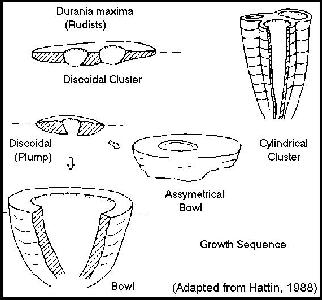

Rudists: A strange looking, highly modified

clam that more or less floated on the surface of the bottom mud. The lower shell looked like a

large funnel or cone with a thick circular collar.

|

LEFT: Rudists (Durania maxima) had heavy cone

shaped shells, often with a large, circular collar. (From Hattin, 1988) The species found

most often (Durania maxima) occurs most commonly in the lower 1/3 of the

chalk. (See Hattin, 1988). However, this Durania

fragment was collected at the contact between the Smoky Hill Chalk and

the overlying Pierre Shale (Early Campanian).

The most common remains are pieces of heavy, finely striated

shell. The upper or free valve of the clam is composed of aragonite and has not been found preserved in the chalk.

RIGHT:

A beautiful example of a Durania maxima colony from the the

Niobrara Chalk in

the exhibits of the Sternberg Museum of Natural History. |

|

|

LEFT: The upper portion (expanded collar) of a Durania

shell collected in southeastern Gove County. More often, the cone shaped shells of Durania maxima

are found flattened and sometimes only circular rim remains. RIGHT:

Upper and lower views of another recently discovered solitary Durania maxima from

the lower Smoky Hill Chalk of southeastern Gove County. |

|

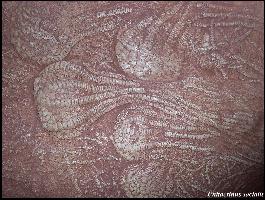

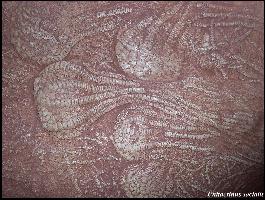

Crinoids (Uintacrinus

socialis) - "Their bodies were about

the shape of half an egg, with an opening in the center, and ten arms radiating from the

margin. These arms were three feet long, with feathered edges. Over the mouth, too, were

smaller arms used to comb off into the mouth the tiny animal life of the sea, that was

strained through, and caught in the meshes of the feathered arms. My boys found hundreds

of these crinoids in the Chalk on Beaver Creek, Kansas, called Uintacrinus

socialis. We enriched many Museums with them."

Excerpted from Charles H. Sternberg's "Hunting Dinosaurs on

the Red Deer River, Alberta, Canada" (1917, p. 156).

|

Crinoids (related to starfish and sea urchins) occurred as

floating colonies. The preserved colonies are found rarely near the middle of the Smoky

Hill chalk formation. There are good examples in the Sternberg and at the Museum of

Natural History at the University of Kansas. LEFT: A portion of a

slab containing dozens of Uintacrinus socialis crinoids. This specimen is in the

KU Museum of Natural History. No, the dark spots are NOT eyes....

RIGHT: A detail from the exhibit specimen of Uintacrinus

socialis at the Sternberg Museum. See close-ups of other individuals in this slab: HERE, HERE and HERE. |

|

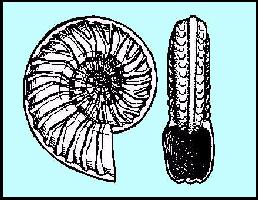

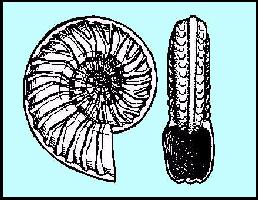

Cephalopods - Ammonites:

|

See the new Kansas Ammonites page HERE LEFT:

A detail from the undersea painting in the Sternberg Museum showing what an living

ammonite may have looked like. Ammonites were creatures that resembled a squid or octopus

living inside the coiled shell of a large snail. They swam backwards the ocean using a jet

of water from their siphons to propel them. The coiled shells are only rarely preserved in

the chalk but other fossil evidence indicates that they lived in the Western Interior Sea.

RIGHT: A specimen of Placenticeras meeki in the collection of the

University of Nebraska State Museum. |

|

|

LEFT: The markings and shapes of ammonite shells are very

distinctive to species. This enables the shells to be used as stratigraphic markers

in those rocks that preserve them. RIGHT: An ammonite shell in the

Sternberg Museum exhibit. The blue marks indicate two or more series of depressions

in the ammonite shell that have been interpreted to be bite marks. Some researchers

believe that "tooth marks" found in ammonite shells indicate that they may

have been prey for mosasaurs and other large predators. |

|

|

LEFT: The impression left by a large ammonite (FHSM

AC-12029-2) collected in northwestern Rooks County,

Kansas. Miller (1968) initially

indentified this specimen as “Brevahites?

sp. B”

in the

Sternberg

Museum

collection. It was subsequently referred to Submortoniceras sp. by

Miller 1969. Ammonites were apparently abundant during the deposition of the Smoky Hill chalk but their

shells were seldom preserved.

RIGHT: A very rare

fragment of an ammonite cast (Texanites sp.) from the Smoky Hill chalk

that would have come from a living specimen about 18 inches in diameter.

Note that the paired aptychi (see photos below) are preserved on this

fragment. Another

fragment is shown HERE. |

|

|

LEFT: An external mold of Clioscaphites choteauensis

from the middle of the Smoky Hill Chalk. According to Cobban, this is the only species of Scaphites

found in the chalk. (About 4 in / 10 cm in diameter).

RIGHT: Another view of the same specimen, with a scale (cm) |

|

|

LEFT: The impression of a heteromorph (not coiled) ammonite

discovered in the Smoky Hill Chalk by Anthony Maltese in Lane County, KS. This is the only

known example of this kind of ammonite in the chalk. The dark line probably represents the

siphuncle. Featured on the new Kansas

Ammonites page HERE

RIGHT: Detail of the opening of the siphuncle.

See: Everhart,

M.J. and Maltese, A. 2010. First report of a heteromorph ammonite, cf. Glyptoxoceras, from the Smoky Hill Chalk

(Santonian) of western Kansas, and a brief review of Niobrara cephalopods. Kansas Academy

of Science, Transactions 113:(1-2):64-70. |

|

Spinaptychus is the term used to describe the paired structures

(aptychi) that probably served as jaw structures for the ammonite (similar to squid

beaks). They look like the inside of a clam shell (smooth) on the inside while the outside

is covered with numerous, short projections or spines. Several types of "Spinaptychi"

are found in the chalk.

|

LEFT: Spinaptychus sp.: An ammonite aptychi specimen (FHSM IP-528) on

exhibit in the Sternberg Museum.. RIGHT: A large ammonite aptychus

in the collection of the Sternberg Museum - FHSM IP-941.

Note this

publication is available on the web:

Fischer, A. G. and R. O. Fay., 1953. A spiny aptychus from

the Cretaceous of Kansas. Bulletin Geological Survey Kansas. 102(2):77-92, 2 pl. |

|

|

LEFT: A pair of aptychi (EPC 1994-13) that I

collected in 1994 from the lower chalk of Gove County (about 4 inches tall).

This specimen was prepared by Neal Larson (Black Hills Institute).

Close-up views of two other fragmentary specimens are HERE.

Note that these structures are rather thin and delicate, with thickness

that varies from 1 to 2 mm, except at the hinges where it is somewhat

thicker.

RIGHT: Another nice Spinaptychus sp. specimen (RMDRC 10-018)

collected in 2010 from the lower chalk of Gove County by Anthony Maltese

(Rocky Mountain Dinosaur Resource Center). This specimen was

prepared, including minor reconstruction, by Neal Larson (Black

Hills Institute). |

|

|

LEFT: A pair of small ammonite aptychi (RMDRC 07-025) as

found from the upper chalk of Logan County. Their small size could

indicate that they are from a straight-shelled baculite, or just a small

ammonite.

RIGHT: Another view of the same pair of aptychi... with a

scale. |

|

Belemnites

and Baculites

- Belemnites

are an extinct group of marine cephalopods, similar in many ways to modern squid

and more closely related to modern cuttlefish. Like squid, cuttlefish and

octopi, belemnites possessed an ink sac, but, unlike the squid, they possessed

ten arms of roughly equal length. The name "belemnite" is derived from

the Greek word belemnon meaning "a dart or arrow."

Baculites

is a genus of extinct, straight-shelled marine cephalopods. They are classed as

a kind of heteromorph ammonite (see above) and lived in the oceans worldwide

throughout the Late Cretaceous Period.

In his paper on the Kansas Niobrara, Williston (1897) also noted that baculites

had never been collected from the chalk, but indicated that Baculites ovatus

had been found in the overlying Pierre Shale near McAllister Butte in western

Logan

County

. Morrow (1935, pl. 53, fig. 7) was the first to describe and figure the

internal mold of a baculite (Baculites sp. cf. B. ovatus) from

chalk of

Trego

County

. Since that time the molds of baculites have been recognized by several authors

(Miller 1968, 1969; Hattin 1982; Hasenmueller and Hattin, 1985; Stewart 1990).

Based on a single, damaged specimen in the

University

of

Kansas

collection, Jeletzky (1955) reported on the first belemnite from the Smoky Hill

Chalk which he identified as Belemnitella praecursor. Two years later,

Miller (1957) also described Belemnitella praecursor from 12 specimens

collected by G.F. Sternberg and M.V. Walker. Those specimens apparently had not

been available to Jeletzky. Following Miller’s publication, Jeletzky (1961)

was able to examine the material in the collection of the

Sternberg

Museum

, and subsequently redescribed them as belonging to the genus Actinocamax,

including two new species, A. sternbergi and A. walkeri. Hattin

(1982) mentions that belemnites are rare in the chalk, but did not figure them.

|

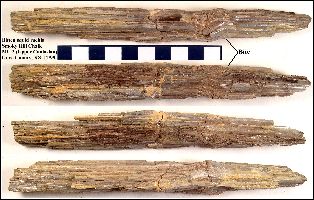

Like

squid, belemnites have a kind of internal skeleton or shell that is

composed of fibrous

calcite. A complete belemnite

shell consists of three parts; however, the fossil that is most normally

collected is called the guard (or rostrum). It is the posterior part of

the shell that was originally located in the tail of the belemnite. The

guard is elongated and bullet-shaped, cylindrical and usually pointed at

one end. The sharp

end points towards the rear of the belemnite. The guard is usually

translucent and is amber or coffee-colored.

(Additional

information HERE)

LEFT: Two views ofFHSM IP-699 belemnite in the Sternberg Museum

collection.

RIGHT: FHSM IP-705 belemnite in the Sternberg Museum collection. |

|

|

LEFT: Two views of FHSM IP-706 belemnite in the

Sternberg Museum collection.

RIGHT: FHSM IP-707 belemnite on exhibit in the Sternberg Museum. |

|

|

Baculites are rarely preserved in the Smoky Hill

Chalk. Like ammonites, their shells are composed of aragonite which

usually dissolves before it can be preserved.

LEFT: A specimen of Baculites maclearni from a concretion in

the Sharon Springs Member (Middle Campanian) of the Pierre Shale in

western Logan County.

RIGHT: A second specimen of Baculites maclearni from a

concretion in the Sharon Springs Member (Middle Campanian) of the Pierre

Shale in western Logan County. This photo clearly shows the sutures

between the segments of the shell. |

|

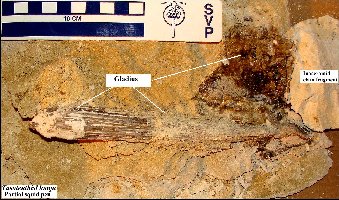

Squid (Teuthids): Squid are soft bodied invertebrates

that probably occurred in great abundance in the warm oceans during this period.

Occasionally, the internal structure (gladius or pen) of the squid is preserved. These

fossils are characterized by long, straight fibers or strands that often appear to be

iridescent. Squid remains are sometimes mistaken for an unusual fish

bone. CLICK HERE FOR

MORE INFORMATION

Tusoteuthis, a 'giant' squid that lived in the Western

Interior Sea, may have been as long as 25 ft. (7.5 m). The evidence of bite marks in

some squid pens shows that squid were eaten by many predators including fish and

mosasaurs. Click here for a picture of a very large Tusoteuthis

longa fossil in the Museum of Geology at the University of Kansas.

|

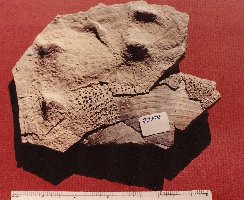

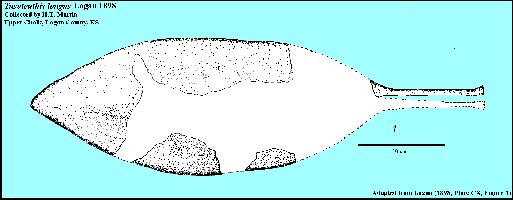

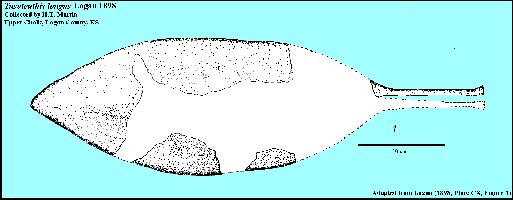

LEFT: A drawing of the type specimen of Tusoteuthis

longus Logan 1898 (Plate CX, Figure 2). Note that the species name was

corrected for gender to longa by Miller (1868).

Logan, W.N. 1898. The invertebrates of the Benton,

Niobrara and Fort Pierre groups. The University Geological Survey of

Kansas, Part VIII, 4:432-518, pl. LXXXVI-CXX.

Miller, H.W., Jr., 1968. Invertebrate fauna and environment

of deposition of the Niobrara (Cretaceous) of Kansas. Fort Hays Studies,

n. s., science series no.8, i-vi, 90 pp. |

|

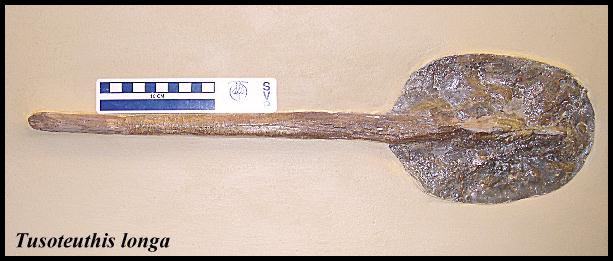

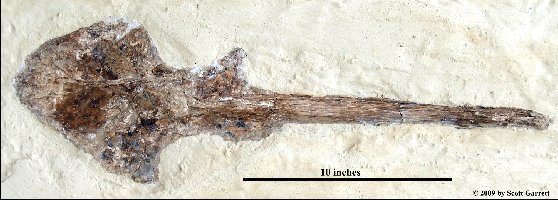

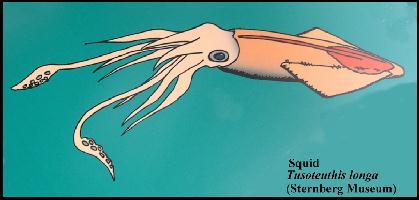

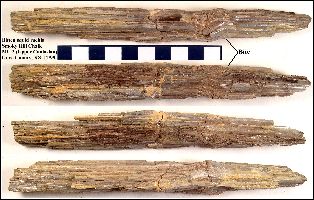

LEFT: Four views of a squid pen that was bitten through by an

unknown predator. Click here for a picture of a fish specimen (Cimolichthys) that died with a squid

in its mouth.

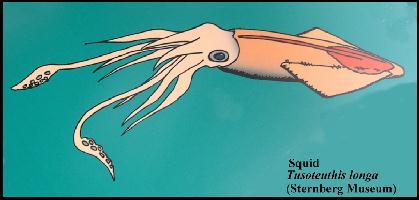

RIGHT: An artist's reconstruction of what the Late Cretaceous squid, Tusoteuthis

longa Logan may have looked like (Sternberg Museum). |

|

Cirripeds (Families Scalpellidae and

Stramentidae)

|

Cirripeds are any of various crustaceans of the

subclass Cirripedia, which includes the barnacles and related organisms

that attach themselves to objects or become parasitic in the adult stage.

LEFT: Upper Cretaceous stalked cirripids (adapted from Hattin 1977)

are often found attached to inoceramid shells. .

RIGHT: A partially disassociated cirriped (Stramentum haworthi) from

the Fairport Chalk of Russell County, KS.

For more information:

Williston, S.W. 1897. The Kansas Niobrara Cretaceous. The University

Geological Survey of Kansas 2:237-246, pl. XXXV.

Logan, W.N. 1897. Some new Cirriped crustaceans from the Niobrara

Cretaceous of Kansas. Kansas University Quarterly 6(4)187-189.

Stevenson, R.E. 1979. Attachment sites of a stalked cirriped in the

Cretaceous Niobrara Sea. Proceedings South Dakota Academy of Science

58:21-29. |

|

Other Invertebrates: Many invertebrates that were

living in the inland sea are represented indirectly by casts, burrows and other evidence.

In some cases, the damage done by cirripids as they bored

into Inoceramid shells is preserved while the actual animal is not. In addition, the

bottom muds of the inland sea may have been relatively low in oxygen and may have not

supported large numbers of invertebrates. There is still much work to be done in defining

the invertebrate community of the inland sea.

Continued on next page.................. A

Field Guide to Fossils of the Smoky Hill Chalk - Part 2; Sharks and Bony Fish

BACK TO INDEX