|

Inoceramids

Giant clams of the Cretaceous

Copyright © 2011 by Mike Everhart

Page Created 11/28/2011

Last revised 11/28/2011

LEFT: A large and relatively uncrushed lower

valve of Volviceramus grandis from the Late Coniacian Smoky Hill

Chalk of Trego County, Kansas.

|

Inoceramids: Some species of clams (bivalves) grew to

giant size in the late Cretaceous, attaining diameters of four feet or more. In cross

section, these shells are composed of prismatic (calcitic)

crystals. The inner, nacreous (Mother of Pearl) layer of the shell (composed

of aragonite) was usually

dissolved during fossilization and the outer portion is usually covered with colonies of

oysters and other invertebrates. Pearls are occasionally found

pressed into the Inoceramid shell. According to Sowerby 1823, Inoceramus

means "fibrous shell," describing the prisms that are visible on the

edge of shell

fragments. Inoceramus cuvieri was the first species of Inoceramus

that was formally described by Sowerby (1814). Several species are found in the

Late Cretaceous rocks of Kansas. At times in the Western Interior Sea, they

provided shelter for various small fishes and at least one species of eel. They

also produced pearls.

|

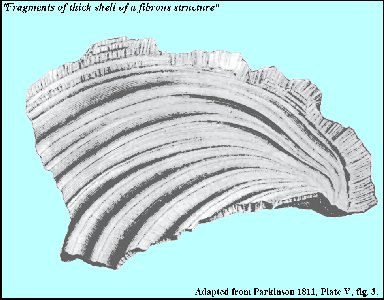

Inoceramid shells were discovered in Great Britain and

France in the late 1700s and early 1800s, but they were seldom found

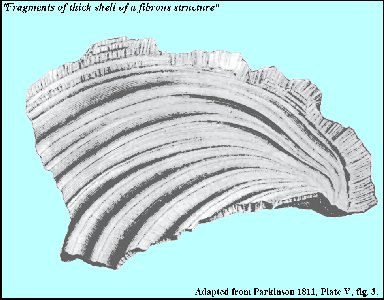

complete. Europe in the James Parkinson (1811b) wrote one

of the first descriptions of inoceramid shell fragments, in this case Inoceramus

cuvieri

from the English chalk:

"Fragments of thick shell of a fibrous structure: The doubts expressed respecting the nature of this

shell, and the observations made with regard

to it, offer another strong point of agreement between the shells of the

two strata. The shell here alluded to is most probably

that represented Org. Rem. vol.

III. pl. V.-fig. 3; the structure of which agrees exactly with that

mentioned as found in the French stratum of- chalk. That shell is however

described as being of a tubular form; it is therefore right to observe,

that fossil

that represented Org. Rem. vol.

III. pl. V.-fig. 3; the structure of which agrees exactly with that

mentioned as found in the French stratum of- chalk. That shell is however

described as being of a tubular form; it is therefore right to observe,

that fossil pinnae do

sometimes

possess

this peculiar structure."

LEFT:

Figure 3 from Plate V in Parkinson's Organic Remains of a Former World

(1811a).

|

|

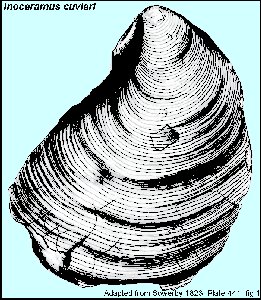

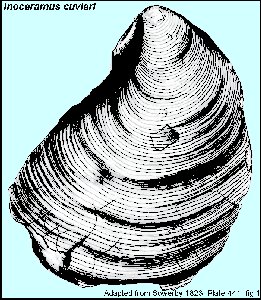

LEFT: A drawing of Inoceramus cuvieri Sowerby

(1814) from Great Britain as figured in Sowerby and Sowerby (1823). I.

cuvieri is fairly common in the Greenhorn and Carlile (Turonian)

formations in Kansas, but I had never paid much attention to it. In late

2011, I needed the citation for the name given by Sowerby and discovered

that it wasn't really that easy to find. In fact the first citation that I

worked with was incredibly wrong. The citation pointed back to seven

volumes of a book written by Sowerby between 1812 and 1843 called "The Mineral Conchology of

Great Britain

, or Colored Figures and Descriptions of those Remains of Testaceous

Animals or Shells, Which have been Preserved at Various Times and Depths

in the Earth." ... After some searching, I found Inoceramus

cuvieri described and figured (left) in Volume 5, but the volume had

been published in 1823, not 1814. So I kept looking. The solution to the

mystery was found on page 457 of a paper published by James Sowerby in

1822.

A note at the beginning of the paper states that it had been read orally on

November 1, 1814 by James Sowerby (1757-1822) before a meeting of the Linnean Society. There was no explanation of the delay in publication:

Sowerby, J. 1822. On a fossil shell of a fibrous

structure, the fragments of which occur abundantly in the chalk strata and

in the flints accompanying it. Transactions of the Linnean Society of

London

XIII: 453-458. Plate XXV.

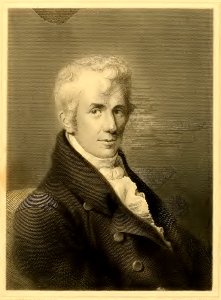

RIGHT:

James Sowerby (1757-1822) portrait in Volume 7. His son, James De Carle Sowerby (1787-1871)

continued the publication of Sowerby's conchology books starting with Volume 5.

Volume 7 was never finished. |

|

|

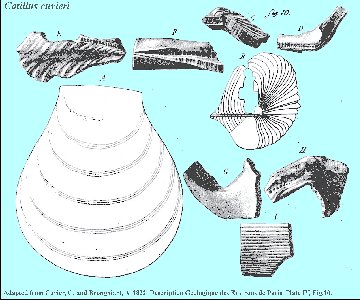

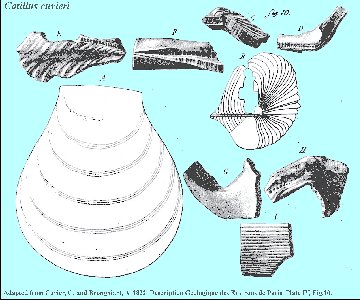

LEFT: It is worth noting that about the same time, Cuvier

(1822) described a similar species from France, and indicating that it differed

from Inoceramus in some ways, but also credited the work of Sowerby

and James Parkinson:

"Fig. 10,

A, E, F, G, H,

I.

Catillus cuvieri, A. BR. (p.15) Inoceramus cuvieri, SOW., PARK.

The

name Inoceramus has been given

to shells which seem to me show so numerous and striking differences that

I could not decide to keep them together, breaking the law I imposed

myself to bring no change in the shells division (family), such as it had

been established by the specialists. One has just to compare the fossil

shells that I unite here under the name of Catillus

with Inoceramus, fig.11 and 12,

pl.

VI, to be stricken by this difference. The species of both these genera

are found in the chalk, but they are located in very distant strata.

It

has seemed logical for me to keep the name Inoceramus

for the gender composed of the

shells that M. Parkinson made known and drew under this name in the first

volume of the Transactions of Geol. Soc. of London., that M. Sowerby

established and presented under this same name at the Linnaean Soc. of

London in 1814, of which figures he just published in plates 305 and

306 in

Conchology, and I have preferred give a new name to the species for

which I see no description nor precise figure anywhere.

I

haven't yet seen an entire individual of this species, so that the genus

itself is difficult to characterize; but with the help of hinge fragments

from various collections, with the figures published by MM. Parkinson and

Mantell, one can succeed in characterizing satisfactorily this genus

so

as it can be recognized by geologists, and give them a way to designate in

a uniform manner so remarkable a shell commonly found in the white chalk."

(Translation by Jean-Michel Benoit) |

| Note here that there is some question as to the meaning

of the genus name, Inoceramus, given on some Internet web sites as

"strong pot" or "a muscle + an earthen vessel").

The issue has been around almost as long as the name and was addressed by

James D.C. Sowerby (1823, p. 56):

"The name Inoceramus,

from [unreadable] (fibra) and

ϰέραμος (testa) is justly objected to

by scholars, as an improperly formed word, and not expressive of

"fibrous shell" which it was intended to signify; it therefore

ought to be changed, but it bas been in use so long, that it has become

general; and, if I were even inclined to act the part of an innovator, to

do so would, I think, only be adding to the confusion already existing in

consequence of Brongniart's naming the type of the Genus, Catillus,

a name not applicable to the whole of the species." |

Volviceramus grandis (Conrad 1875) - Late

Coniacian

| Volviceramus grandis: A common clam found in the lower

third (late Coniacian) of the chalk. The lower shells are thick and generally bowl shaped.

In many areas, the surface of the chalk is littered with thousands of fragments of this

shell, some of which may resemble bone in outward appearance. Examination

of the edge of the fragment will determine if it is bone (porous) or shell

(crystalline structure). |

|

LEFT: Volviceramus grandis - A common, large bivalve in

the lower Smoky Hill chalk. This lower valve measures 12 inches by 10 inches. Click here for a view of the other side of this

shell which is encrusted with Pseudoperna congesta oysters. RIGHT:

A juvenile V. grandis lower valve with attached P. congesta oysters.

This shell measures about 2.5 by 2.0 inches. The shell crushing shark, Ptychodus, most likely fed on shells that were about

this size. |

|

|

LEFT: A field photograph of a medium sized Volviceramus grandis

shell that was relatively uncrushed and shows the depth and the bowl shape. Specimen was

discovered in the

lower chalk of Trego County RIGHT: A field photograph of a

fairly complete V.

grandis shell from the lower chalk of Trego County with the upper (right) valve still

in place, and completely covered with Pseudoperna congesta oysters. The

bottom of this specimen was also completely covered with oysters. |

|

Cladoceramus undulatoplicatus Early Santonian

|

Cladoceramus undulatoplicatus: A large

inoceramid that

occurs in a limited zone about 1/3 of the way up from the base of the chalk

(above Marker Unit 7). This zone straddles the boundary between the

Coniacian and Santonian ages, making it useful world-wide as a

stratigraphic marker. The shell of Cladoceramus undulatoplicatus

is

characterized by deep ripples and it has been referred to as the "Snowshoe Clam." LEFT:

A field photo from 1996 showing the edge of a large Cladoceramus undulatoplicatus eroding from the edge of

a gully in the lower Smoky Hill Chalk, Gove County, Kansas. This shell was

near a Pteranodon sternbergi specimen

discovered by Pam Everhart and helped to establish the age of those

remains.

|

Platyceramus platinus Logan 1898 - Latest Coniacian

through Early Campanian:

|

Platyceramus platinus is a very large clam shell that occurs throughout the chalk,

sometimes reaching more than four feet in diameter in Kansas. They are thought to be the largest

clams ever, reaching nearly 9 feet in length (3-4' width) in the Niobrara of

Colorado (see Kauffman, et al, 2007). As the name implies, these shells are

relatively flat and often very thin. While alive,

the interior sometimes served as shelter for schools of small fish which are occasionally

preserved inside as fossils pressed into the shell. (See Stewart 1990 and

others) LEFT: The

exhibit specimen of Platyceramus platinus (FHSM IP-532) at the Sternberg Museum.

This shell is about 3 ft. wide and 3.5 feet long (Scale = 10 cm). As

collected by G.F. Sternberg, this would have been the lower side of the

specimen as discovered (Here in a

1960s photo, Dr. L.D. Wooster looks on as George Sternberg points

out a colony of oysters.)

|

|

LEFT: Part of a large Platyceramus platinus eroding from

the middle of the Smoky Hill Chalk. (Scale = 6 in / 15 cm). There has been some

controversy regarding the orientation of these clams as they sat on the sea bottom because

oysters (Pseudoperna congesta) have been found on both sides. Stewart (1990)

suggested that they sat upright, something like modern giant clams are found in modern

coral reefs. Others (Kauffman, et al., 2007) indicate that they usually occurred in a

recumbent mode, with the left valve on the sea floor. Since the shells are somewhat bowl

shaped, this would allow oysters to colonize the lower portion around the edges.

Otherwise, the shell could have been colonized after it had died and been turned

over (although it is unknown "how" it would have been turned

over).

RIGHT: My concept of a giant (> 1m) Platyceramus

platinus resting on the sea floor with a rather large area of the rim of the lower

shell exposed above the sediment... a great location for oysters looking for a home. |

|

|

LEFT: A very large P. platinus shell eroding from the

lower chalk of Trego County. The shell is almost completely covered with Pseudoperna

congesta oysters. The shell is about 1 m (39 in.) across. RIGHT:

Platyceramus platinus shells were so large that they provided shelter for schools

of small fish. Sometimes the fish were trapped inside the clam's shell when it died.

This picture shows skeletal fragments of small fish that were preserved inside a Platyceramus

platinus shell from the Smoky Hill Chalk. |

|

|

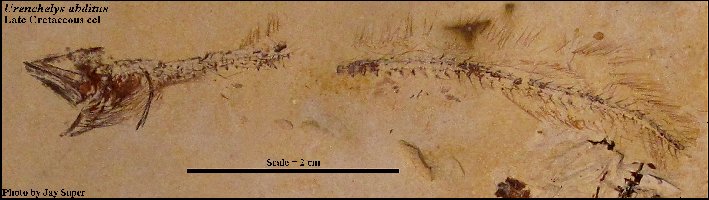

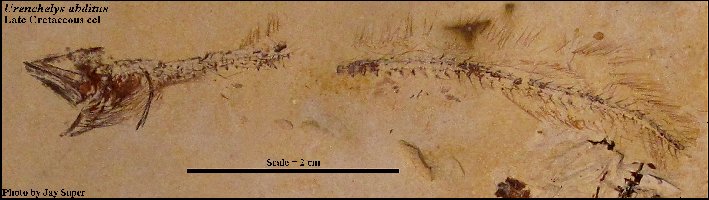

LEFT: A rare Cretaceous Urenchelys eel preserved

on a Platyceramus shell from the mid-Santonian Smoky Hill Chalk in

Gove County. (see Wiley and Stewart 1981)

RIGHT: The remains of two small fish preserved in the same shell as

the eel (left). |

|

Inoceramid pearls

|

As noted by Brown (1940) and Kauffman (1990),

sometimes small round nodules are found attached to inoceramid

shells. They are the remains of pearls that were fossilized along with the clam shell. The

nacre or "mother of pearl" luster is not preserved in inoceramid

pearls. This is because the pearly, nacreous color associated with true

pearls is made up of a mineral called aragonite. In the Smoky Hill chalk, the aragonite is

not preserved. Inoceramid shells and pearls have lost the thin inner pearly aragonite

layer, and are solely composed of calcite. This also means that some kinds of shells, like

those of ammonites, were not preserved because they are composed entirely of aragonite. An

1940 article in the Hays Daily News noted that George Sternberg had donated 50 pearls from

the Smoky Hill Chalk to the Smithsonian Institution, and a scientific paper was published

on their occurrence (Brown, 1940).

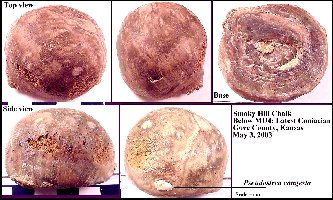

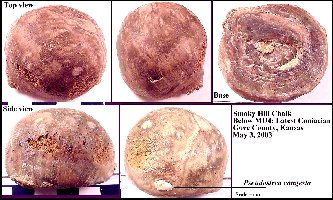

LEFT: Several views of a giant fossil

pearl I discovered in the lower Smoky Hill Chalk, Gove County, Kansas. The specimen is the size of half a golf ball.

(Scale = cm) |

|

LEFT: Three 'pearls' attached to fragments of Inoceramid shells.

The fourth pearl in the lower right was unattached and is a badly formed hemispherical

pearl. RIGHT: A side view of an inoceramid

"blister" pearl showing the

underlying inoceramid shell.

Another group of

pearls and a close-up of

a large pearl from the Smoky Hill Chalk. (Scale =mm) |

|

|

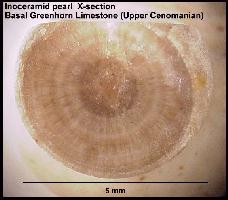

PEARLS FROM OTHER FORMATIONS IN

KANSAS

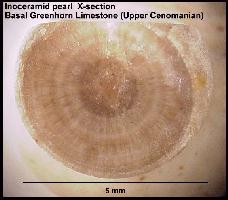

LEFT: Two small pearls (4-5 mm) from the base of the Lincoln Limestone Member

of the Greenhorn Limestone Formation (Upper Cenomanian) in Russell County, Kansas.

(Scale = mm)

RIGHT: A cross section of the larger pearl shown at left showing. the

concentric layers. |

|

| Williston (1897, p. 241) in his paper on the Kansas

Niobrara Cretaceous made the following comments:

"INVERTEBRATES.

Of

the Mollusca, Ostrea congesta is

of very great abundance in the Rudistes beds, but much less common in the Hesperornis

beds. They are found attached to other shells, and it may perhaps be in

consequence of the fewness of large shells in the upper strata that their

comparative rarity- may be ascribed. Several species of Inoceramus

are apparently found in all horizons, but the Haploscaphas are abundant

only in the lower horizons, and I never have found H.

grandis or those allied to that species in the upper horizons. On the

Smoky Hill River

near the mouth of the Hackberry [Creek] there are places where these

shells can be gathered by the wagon load, often distorted, but not rarely

in extraordinary perfection. A very thin shelled Inoceramid [Platyceramus

platinus] measuring in the largest specimens forty-four by forty-six

or eight inches is not rare over a large part of the exposures. Invariably

where exposed, as they sometimes are in their entirety on low fiat mounds

of shale, they are broken into innumerable pieces. For that reason, I have

never known of one being collected complete, or even partially complete.

Notwithstanding their great size the shell substance is not more than an

eighth of an inch in thickness."

|

Suggested references:

Brown, R.W. 1940. Fossil pearls from the Colorado group of western

Kansas. Washington Academy Science 30(9):365-374. (article

in TIME magazine, 1940)

Cuvier, G. and Brongniart, A. 1822. Description

Géologique des Environs de Paris. Paris, 428 pp. Pl.

I-XI.

Conrad, T.A. 1875. Descriptions of Haploscaphae from

the

Niobrara

. pp. 23-24 in Cope, E.D., The Vertebrata of the Cretaceous formations of the

west,

U.S.

Geol.

Survey

Territories

Dhondt,

A V. and Dieni, I. 1990. Unusual Inoceramid-spondylid

association from the Cretaceous Scaglia Rossa of Passo del Brocon (Trento, N.

Italy) and its palaeontological significance. Memorie di Scienze

Geologiche, 42:155-187, 10 fig. 3 pl.

Hattin, D.E. 1962. Stratigraphy of the Carlile Shale

(Upper Cretaceous) in Kansas. State Geological Survey of Kansas, Bulletin 156,

(University of Kansas pub.) 155 p. 2 pl.

Hattin, D.E. 1965. Stratigraphy of the

Graneros Shale (Upper Cretaceous in central Kansas. Bulletin 178, Kansas

Geological Survey, 83 pp.

Hattin, D.E. 1975. Stratigraphy and

depositional environment of the Greenhorn Limestone (Upper Cretaceous) of

Kansas. Bulletin 209, Kansas Geological Survey, 128 pp.

Hattin, D.E., 1982. Stratigraphy and depositional

environment of the Smoky Hill Chalk Member, Niobrara Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) of

the type area, western Kansas. Kansas Geological Survey Bulletin 225, 108 pp.

Hattin, D.E. and Siemers, C.T. 1978. Upper

Cretaceous stratigraphy and depositional environments of western Kansas.

Guidebook Series 3, AAPG/SEPM annual meeting, Kansas Geological Survey, 55 pp.

(Reprinted 1987)

Kauffman, E.G. 1972. Ptychodus predation upon a

Cretaceous Inoceramus. Palaeontology, 15(3):439-444.

Kauffman, E.G. 1990. Giant fossil inoceramid bivalve pearls. pp. 66-68 In

Boucot, A. J., Evolutionary Paleobiology and Coevolution. Elsevier, Amsterdam.

Kauffman, E.G., Harries, P.J., Meyer, C.,

Villamil, T., Arango, C. and Jaecks, G. 2007. Paleoecology of giant Inoceramidae (Platyceramus)

on a Santonian seafloor in Colorado. Journal of Paleontology

81(1):64-81.

Logan, W.N. 1897. The upper Cretaceous of Kansas; with an

introduction by Erasmus Haworth: Kansas Geological Survey, Vol.2, p. 195-234

Logan, W.N. 1898. The invertebrates of the Benton,

Niobrara and Fort Pierre groups. The University Geological Survey of Kansas, Part

VIII, 4:432-518, pl. LXXXVI-CXX.

Logan, W.N. 1899. Some additions to the Cretaceous

invertebrates of Kansas. Kansas University Quarterly 8(2):87-98, pl.

XX, XXI, XXII, XXIII. (mostly oysters)

Miller, H.W. Jr., 1968. Invertebrate fauna and environment of deposition

of the Niobrara (Cretaceous) of Kansas. Fort Hays Studies, n. s., science series

no.8, i-vi, 90 pp. (Tusoteuthis longa and Niobrarateuthis bonneri

are described, pp 53-56)

Miller, H.W. 1969. Additions to the fauna of the Niobrara Formation of

Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 72(4):533-546. (published July

15, 1970)

Parkinson, J. 1811a.

Organic Remains of a Former World – An Examination of the Mineralized

Remains of the Vegetables and Animals of the Antediluvian World. Vol III,

Whittingham and Roland, London, i-xv, 479 pp., plates I-XII, index.

Parkinson,

J. 1811b.

Observations on some of the strata in the neighborhood of

London

, and on the fossil remains contained in them. Transactions of the

Geological Society of

London

1(XIV):324-354.

Roemer,

F. 1852. Kreidebildungen von Texas und ihre organischen

Einschlusse. vi +100 pp. Adolph Marcus,

Bonn

.

Sowerby, J. 1822. On a fossil shell of a fibrous

structure, the fragments of which occur abundantly in the chalk strata and

in the flints accompanying it. Transactions of the Linnean Society of

London

XIII: 453-458. Plate XXV.

Stewart, J.D. 1990. Preliminary account of

holecostome-inoceramid commensalism in the Upper Cretaceous of Kansas. pp.

51-57, In Boucot, A. J., Evolutionary Paleobiology and Coevolution.

Elsevier, Amsterdam.

Stewart, J.D. 1990. Niobrara Formation

vertebrate stratigraphy, pages 19-30, In Bennett, S. C. (ed.),

Niobrara Chalk Excursion Guidebook, The University of Kansas Museum of Natural

History and the Kansas Geological Survey.

Stewart, J.D. 1990. Niobrara Formation

symbiotic fish in inoceramid bivalves. p. 31-41 In S. Christopher

Bennett (ed.), 1990 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Niobrara Chalk excursion

guidebook. Museum of Natural History and the Kansas Geological Survey, Lawrence,

KS.

Wiley, E.O. and Stewart, J.D. 1981. Urenchelys

abditus, new species, the first undoubted eel (Teleostei:

Anguilliformes) from the Cretaceous of North America. Journal of Vertebrate

Paleontology 1(1):43-47.

Williston, S.W. 1897. The

Kansas Niobrara Cretaceous, The University Geological Survey of Kansas,

2:237-246.