|

Cimolichthys nepaholica (Cope

1872)

Barracuda of the Western Interior Sea

Copyright © 2004-2012 by Mike Everhart

Created 07/28/2004: last updated 07/18/2012

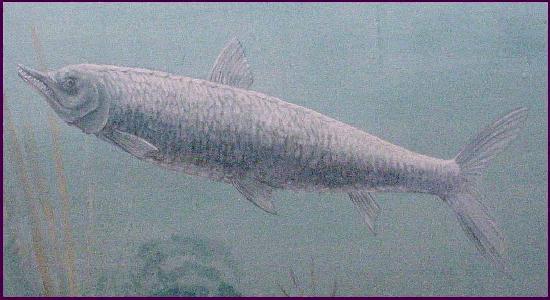

LEFT: Cimolichthys nepaholica from

a detail in a mural at the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History, Lawrence,

Kansas. |

|

One of the more

common species of fish found preserved in the Smoky Hill Chalk is a medium-sized predatory

fish called Cimolichthys nepaholica. It was also the first specimen of

articulated remains of anything that I ever found in the chalk. The pictures at LEFT

and RIGHT were taken in 1968 after I had uncovered a fairly large Cimolichthys that

had been preserved more or less upright on the sea bottom. The remains were discovered low

in the Smoky Hill Chalk (about MU 2 - Late Coniacian) of Ellis County. |

|

|

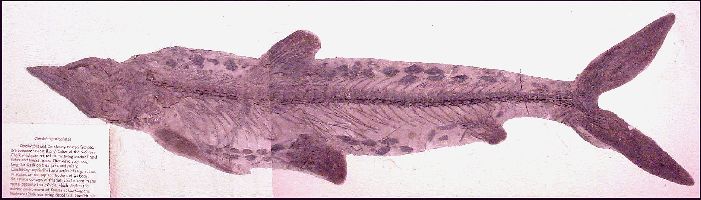

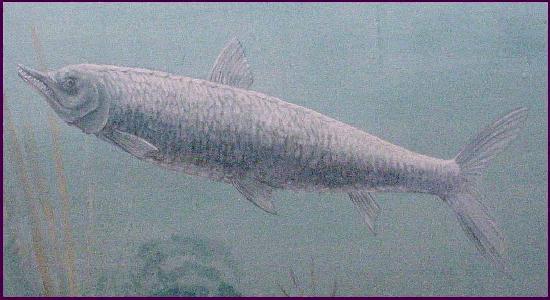

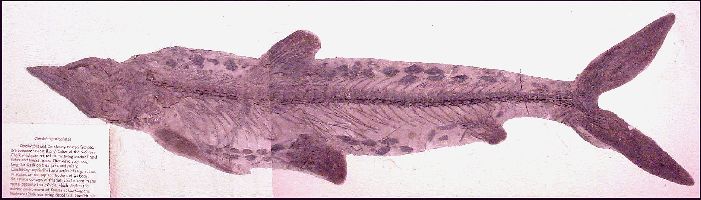

LEFT: A large and fairly complete Cimolichthys nepaholica in the

exhibits of the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History. This specimen is about 2 m

(6 ft) in length, and shows the large scutes (heavy scales) that are typical of the

species. Note that the top of the skull is actually more convex than the concave

appearance preserved in this specimen and the above painting. |

The genus name Cimolichthys

(cimoli = (Greek) a white chalky clay; ichthys = fish) had been coined by Leidy in 1857 in

describing fish remains (C. levesiensis) from the English Chalk. According to

Alvaro Mones (pers. comm., 2004), "cimoli is new Latin (from Greek -

kimolia), a white clay from the Aegean island of Cimolus of the archipelago of the

Cyclades. In Antiquity it was well known for the high quality of the dried fishes it

produced." Earl Manning (pers. comm., 2004) noted that the English type species C.

levesiensis was named for the town of Lewes, in Sussex where the fossil was

found. The Lewes Formation was named later and is the basal member of the English

upper chalk. This chalk formation (Turonian) makes up part of the White Cliffs of Dover.

| The genus name has been confused over the years in large part because E. D. Cope named a new genus and species, "Empo"

nepaholica (1872a, p. 347) from the Niobrara Chalk along

with four new species of Cimolichthys (ibid., p. 351-353; C. sulcatus, C. anceps, C. semianceps, and C. gladiolus)

from Kansas in the same paper. Cope (1872b, p. 345) later described E. nepaholica as "a fish as large as pike of forty pounds." He

also noted (ibid., p. 347) that the name "Cimolichthys was applied by Dr. Leidy to a fish erroneously referred by

Agassiz and Dixon to Saurodon, Hays. He [Leidy] did not characterize it; and until the

barbed palatine teeth, characteristic of it, are discovered in our species, their

reference to it will not be fully established." |

Systematic Paleontology

Order Salmoniformes Greenwood, Rosen, and Myers,

1966

Suborder Cimolichthyoidei

Family Cimolichthyidae Goody, 1969

Genus Cimolichthys Leidy 1857

Cimolichthys nepaholica (Cope 1872) |

Two years

later, Cope (1874, p. 46) revised the spelling

of “nepaholica” to “nepaeolica” (nepćolica), changed the genus of C. sulcata to "Empo"

sulcatus, and changed C. semianceps

to "Empo" semianceps, and also

added two new species of "Empo":

E. merrillii and E. contracta. While C. gladiolus

eventually became recognized as Enchodus gladiolus, C. anceps literally

disappeared. Goody (1976, p. 102) noted that the type specimen could not be found. Goody

also determined that, based on Cope's description of the type, the specimen was more

likely the ectopterygoid of Enchodus petrosus.

|

As noted above, Leidy's Cimolichthys

lavesiensis is much older (Turonian) than the specimens

of "Empo" nepaholica examined by Cope (Late Coniacian - Early Campanian). It doesn't appear that Cope ever accepted that Cimolichthys

Leidy and "Empo" Cope were the same genus. Cope (1875, p. 230) noted

that he “formally referred some of the species of Empo

to the genus which embraces the fish called by Leidy Cimolichthys

levesiensis; but I find that they do not possess the same type of teeth. …

The genus therefore takes this name [Empo].”

Cimolichthys specimens are usually poorly preserved and the teeth are quite

fragile. Cope (1875, Plate 52 and 53) was the first to illustrate Cimolichthys.

Manning (pers. comm. 2004) noted that Cope is one of a few to figure the isolated dermal

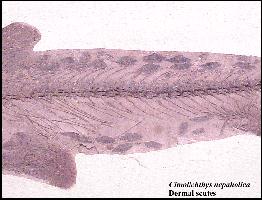

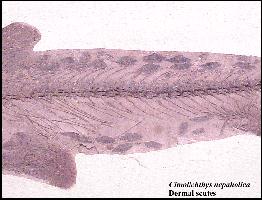

scutes (ibid., Plate 53, fig. 9). LEFT: RIGHT:

Dermal scutes of Cimolichthys nepaholica on the exhibit specimen

at the University of Kansas. |

|

"Empo"

nepaholica and the four (six?) new Cimolichthys / "Empo"

species of Cope were actually fragments of the same kind of fish, and all were synonymized

by Loomis (1900 - in German) and by Hay (1903). By virtue of being the first of the

species names published in Cope's (1872) paper, the species is rightfully called nepaholica*. Since the genus name Cimolichthys Leidy 1857 has precedence over that of "Empo" Cope 1872, the correct name for Cope’s many

“species” becomes Cimolichthys nepaholica.

Like the very similar problem with Xiphactinus Leidy and "Portheus" Cope, the name "Empo" has had a long, if ill-deserved, life of its own and is

still found on labels in museum exhibits and collections. As for the other species names,

Goody (1970, p. 2) indicated “there is no reason for retaining Cope’s various

species that are based mainly on isolated teeth and fragments of jaw bones.”

(* NOTE: The

species name most likely comes from "Nepaholla," an earlier Indian name for the

Solomon River (Solomon’s Fork of the Smoky Hill River) meaning "water on a

hill" (Rydjord, 1972, p. 109).)

While

not closely related, Cimolichthys can be

visualized as being a Cretaceous barracuda (or a freshwater pike, as suggested by Cope) in

appearance. However, Cimolichthys, like Enchodus, is in the same order as modern salmon. The fish grew to

almost 2 m (6 ft) in length and the skull, with triple rows of teeth set in the narrow

lower jaws (Hay, 1903) is readily recognizable. Cope's

(1875) Figure 6 in Plate 53 also shows 3 rows of teeth on the dentary and in his

description of the genus "Empo" (ibid., page 228), he mentions that

“the dentarys support several series of teeth; one of the large ones on the inner

side and several smaller on the outer.” While their remains are frequently found, good specimens are

rare because the skull is lightly constructed and tends to either have come apart prior to

preservation or as a result of weathering.

|

LEFT and RIGHT: A dorsal view of the skull of a large Cimolichthys (FHSM

VP-73) in the Sternberg Museum collection that is preserved in an unusual dorso-ventral

orientation. Note the ornamentation on the top of the skull (neurocranium), and the

operculum (RIGHT) that covers the gills . |

|

|

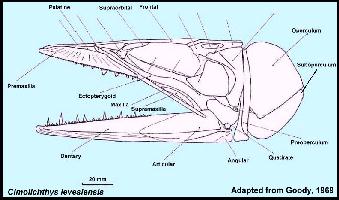

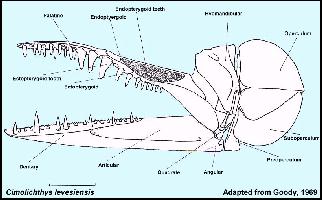

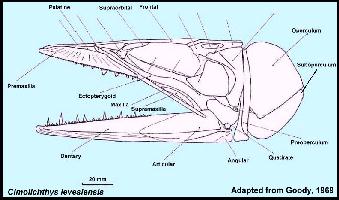

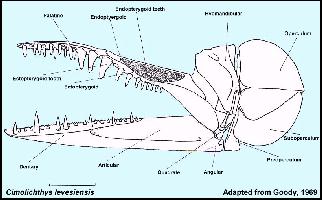

LEFT: Restoration of the skull of Cimolichthys levesiensis in

lateral view (after Goody, 1969). RIGHT: Restoration of the jaws (right) of

Cimolichthys levesiensis in medial view as taken from BMNH P.1811 (after Goody,

1969). |

|

We

can assume that Cimolichthys had a voracious

appetite for fairly large prey because of a number of specimens that have been found with

the remains of an undigested last meal inside. One of the strangest “death by

gluttony” occurrences in the fossil record was reported by both Kaufmann (1990), and

Stewart and Carpenter (1990; see also Carpenter, 1996) in regard to a specimen of Cimolichthys discovered in the Pierre Shale of Wyoming.

|

LEFT: In this instance, the Cimolichthys

(UCM 20556 - skull at far left) apparently died with a

large squid (Tusoteuthis longa - UCM 29667) lodged

in its mouth. The squid had been swallowed tail first as evidenced by the gladius

(squid pen) being found inside the body of the Cimolichthys. However, the open jaws of the fish appear to indicate that

part of the head and/or tentacles of the squid were still outside the mouth. This probably

meant that the fish’s gills were blocked from getting oxygen from the water, causing

death by suffocation. (2012 photo by Trish Weaver; See also Fig. 176 in Kaufmann,

1990). |

Another unusual Cimolichthys

specimen (FHSM VP-15065) in the Sternberg Museum was collected by Greg Winkler and

Pete Bussen in the early 1990s from the lower chalk (Late Coniacian) of western Gove

County. In this case, the skull of a large (1.8 m) Cimolichthys was found eroding

out of the chalk. Much of the skull was already lost, but the rest of the fish was

complete back to the tip of the tail. When the specimen was initially prepared, it was

found to contain not only a large Enchodus (FHSM VP-15066) but also the remains of

another smaller, unidentified fish (FHSM VP-15067) as a last meal. At this point,

it’s uncertain if both fish inside the Cimolichthys were consumed by the

larger fish, or if this a classic case of a “fish-in-a-fish-in-a-fish.” In

either case, the partially digested condition of the Enchodus leads me to believe

that the Cimolichthys died within a short time after eating it.

|

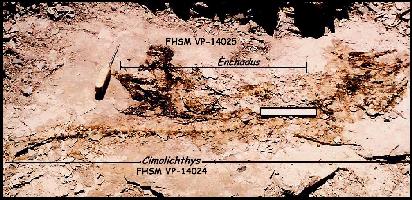

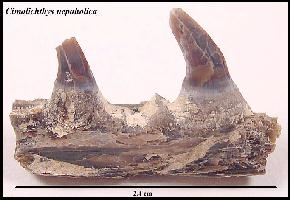

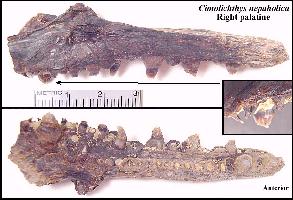

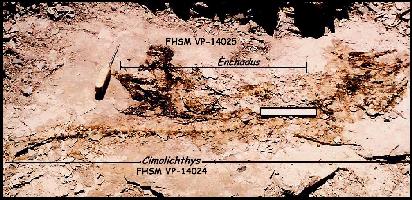

In a similar situation, I found a 1.3 m (4 ft.) Cimolichthys (FHSM

VP-14024) with a .7 m (2 ft.) long, partially digested Enchodus petrosus

(FHSM VP-14025) inside in the lower chalk of southeastern Gove County in 1994. Both

palatine bones of the Enchodus, minus the large fangs, were located near the anus

of the larger fish. Besides being an indication that the prey had been swallowed

head-first, it also explains our field observation of finding an unusual number of

partially digested Enchodus palatine bones, and no other associated remains.

Being the heaviest bones in the skull of the Enchodus, mostly indigestible and

located at the anterior end of the skull, they were probably expelled while the rest of

the prey was still being digested. The large teeth, however, appeared to have been broken

off the palatines and were not found in the rest of the remains. |

The skull of Cimolichthys has been figured by Cope,

(1875), Loomis (1900), Hay (1903) and Goody (1970). The photos below show features that

are not found or are poorly represented in these papers.

|

LEFT: Vertebrae from a large, but scattered Cimolichthys

(EPC 1988-16) that we collected in October 1988 from Gove County. These vertebrae were

from right behind the skull. (Scale = cm) RIGHT: Close-up of two

vertebrae from EPC 1988-16. (Scale = mm) |

|

It is probable that Cimolichthys was preyed upon by larger

fish and mosasaurs. Although they were not noted by Bardack (1965) as being the stomach

contents in any of the Xiphactinus audax specimens he

surveyed, I did find partially digested Cimolichthys vertebrae in the abdominal

region of a Tylosaurus proriger (FFHM 1997-10) that I collected in 1996-97. While

their remains have not been reported to be preserved as stomach contents of other

predators, many of the severed tails

which we commonly find in the chalk are from Cimolichthys (See a much larger, detached Ichthyodectid tail

here).

One interesting feature often observed in Cimolichthys remains

in the field are the “cone on

cone” calcite crystals (steinkerns) that often fill the conical hollows between

the deeply cupped vertebrae.

|

LEFT: The crushed skull of the exhibit specimen (dorsal and right

lateral view) of Cimolichthys at the Sternberg Museum of Natural History. RIGHT:

A ventral view of a small Cimolichthys skull in our personal collection. Found by

Pam Everhart in 1988. Parts of the hyoid apparatus are visible in this view. |

|

|

LEFT and RIGHT: Details of the jaws from a Cimolichthys

skull in the exhibits of the Fryxell Museum of Geology, Augustana College, Rock Island,

IL. This specimen was collected and prepared by George F. Sternberg. |

|

Other

Oceans of Kansas webpages on Late Cretaceous fish:

Field Guide to Sharks and Bony

Fish of the Smoky Hill Chalk

Sharks:

Kansas Shark Teeth

Cretoxyrhina and Squalicorax

Ptychodus

Chimaeroids

Bony Fish

Pycnodonts and Hadrodus

Plethodids:

Pentanogmius

Martinichthys

Thryptodus

Bonnerichthys

Protosphyraena

Enchodus

Cimolichthys

Pachyrhizodus

Saurodon and Saurocephalus

Xiphactinus

Suggested references:

Bardack, D. 1965. Anatomy

and evolution of Chirocentrid fishes. University of Kansas Paleontology Contributions.

Article 10, 88 pp. 2 pl.

Carpenter, K. 1996. Sharon Springs

Member, Pierre Shale (Lower Campanian) depositional environment and origin of its

vertebrate fauna, with a review of North American plesiosaurs. Unpub. Ph.D. dissertation,

University of Colorado, 251 pp.

Cope, E. D. 1872. On the

families of fishes of the Cretaceous formation in Kansas. Proceedings of the American

Philosophical Society 12(88):327-357.

Cope, E. D. 1872. On the geology and paleontology of

the Cretaceous strata of Kansas. Preliminary Report of the United States Geological

Survey of Montana and Portions of the Adjacent Territories, Part III - Paleontology, pp.

318-349.

Cope, E. D. 1874.

Review of the vertebrata of the Cretaceous period found west of the Mississippi

River. U. S. Geological Survey Territory Bulletin 1(2):3-48.

Cope, E. D. 1875. The

vertebrata of the Cretaceous formations of the West. Report, U. S. Geological Survey

Territory (Hayden). 2:302 p, 57 pls.

Goody, P.C. 1969. The relationships of

certain Upper Cretaceous teleosts, with special reference to the myctophoids. Bulletin of

the British Museum (Natural History), Geology, Geological Series Supplement 7, 255 p.

Goody, P.C. 1970. The

Cretaceous teleostean fish Cimolichthys from the Niobrara Formation of Kansas and

the Pierre Shale of Wyoming. American Museum Noviates 2434:29 pp.

Hay, O. P. 1903. On a

collection of upper Cretaceous fishes from Mount Lebanon, Syria, with descriptions of four

new genera and nine new species. Bulletin of the American Museum Natural History

19:395-452, pl. XXIV-XXXVII.

Kauffman, E.G. 1990. Cretaceous fish

predation on a large squid. pp. 195-196 In Boucot, A.J., Evolutionary

Paleobiology and Coevolution. Elsevier, Amsterdam.

Leidy, J. 1857. Remarks on Saurocephalus

and its allies. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 11: 91-95, with

pl. vi.

Loomis, F.B.

1900. Die anatomie und die verwandtschaft der Ganoid- und Knochen-fische aus der

Kreide-Formation von Kansas, U.S.A. Palaeontographica, 46:213-283.

Rydjord, J. 1972. Kansas place names. Univ. Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK. 613 pp.

Stewart, J. D. and Carpenter, K. 1990.

Examples of vertebrate predation on cephalopods in the Late Cretaceous of the Western

Interior. pp. 203-208 In Boucot, A.J. (Ed.), Evolutionary paleobiology of

behavior and coevolution. Elsevier, New York.