The Bunker Mosasaur

Copyright © 2000-2012 by Mike Everhart

Updated 01/17/2012

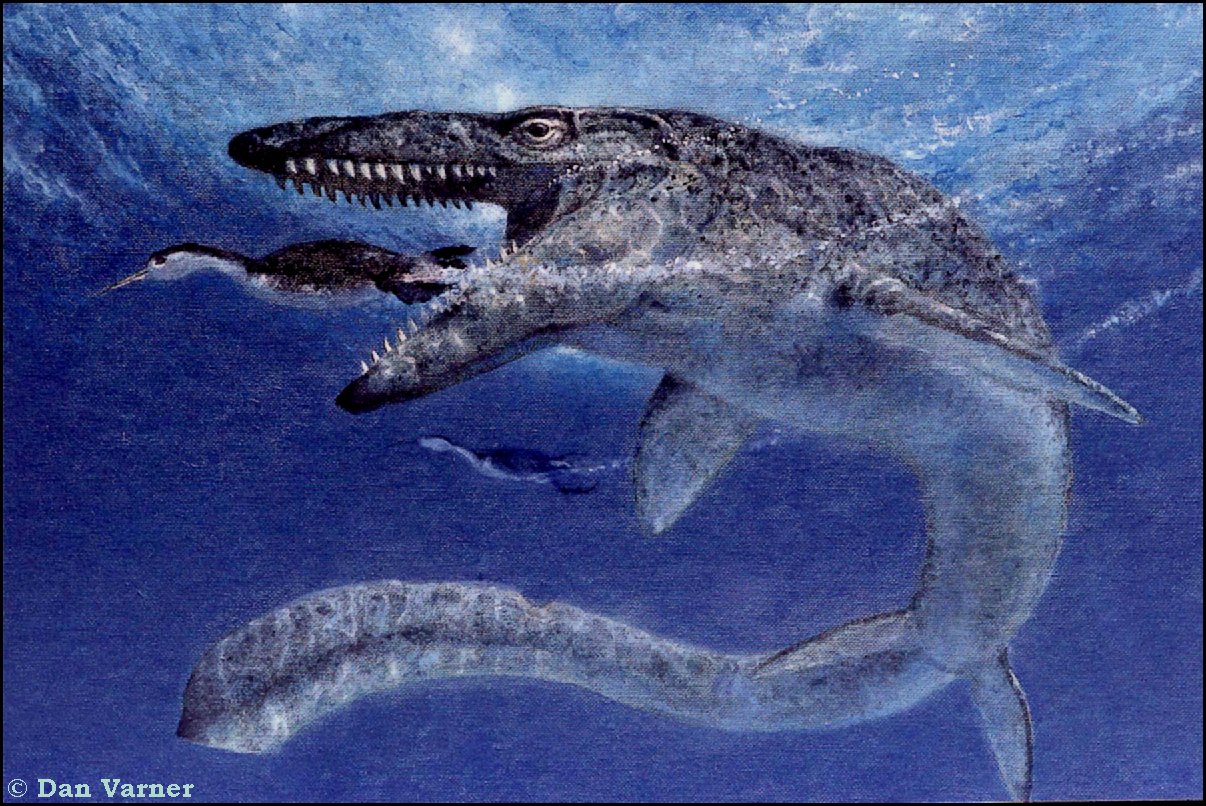

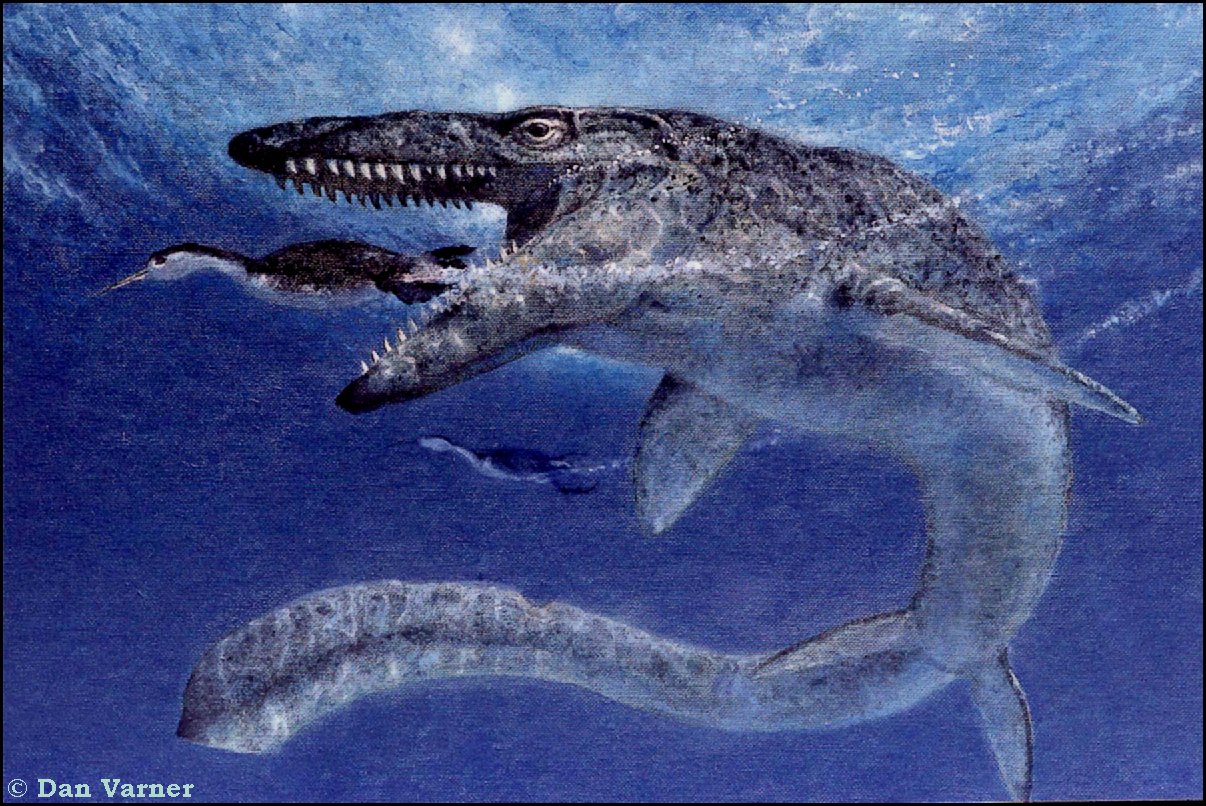

LEFT: Tylosaurus and Hesperornis. Copyright © Dan Varner; used with permission of Dan Varner

|

The Bunker Mosasaur

Copyright © 2000-2012 by Mike EverhartUpdated 01/17/2012

LEFT: Tylosaurus and Hesperornis. Copyright © Dan Varner; used with permission of Dan Varner |

About a hundred years ago (1911), a group from the University of Kansas led by C.D. Bunker came across the remains of a huge mosasaur eroding from the upper Smoky Hill Chalk or lower Pierre Shale Formation of Western Kansas. The skull itself (shown below) was almost six feet in length!! Although Bunker and his men were not experienced in collecting marine reptiles, this find was too spectacular for them to pass up. Without waiting for further instructions, they uncovered the specimen and packed up all the pieces for shipment. An interesting historical note is that Bunker's field notes were recently rediscovered (August, 1999) at the University of Kansas.

At almost 12 meters in length, the Bunker mosasaur (probably a Tylosaurus proriger) turned out to be one of the largest mosasaurs ever collected in North America. Eventually it was placed in the paleontology collection of Natural History Museum of the University of Kansas, and has been in storage ever since. The condition of the specimen upon arrival at the Museum was not good, and over the years, it deteriorated as it was moved from place to place. Even so, it was truly a monster of a mosasaur by anyone's measure and deserved far more recognition than it had gotten.

By special arrangement with the Museum of Natural History, Triebold Paleontology was allowed to work on the restoration of the specimen, assembling broken bones, molding parts and casting a replica of what the skeleton of the mosasaur would have looked like 82 million years ago. The specimen was assembled by museum staff and is now is suspended overhead in the entry way of the Museum of Natural History at The University of Kansas. It is very awesome sight when one realizes that this creature and many others like it were prowling through the oceans of the Late Cretaceous, looking for their next meal.

The following pictures were taken in the Museum of Natural History at The University of Kansas. Since mosasaurs are long and slender, they are notoriously difficult to photograph. Even though the museum staff did an outstanding job of fitting this specimen into the space available (doing a descending "S" curve), there was still no way to get a picture of the entire mosasaur. Hopefully these photos will give you some idea of the size and beauty of this spectacular new exhibit. Certainly worth a stop if you are near The University of Kansas at Lawrence, Kansas.

|

A close-up view of the 'business end' of this Tylosaurus proriger (KUVP 5033). The skull of this mosasaur is almost 6 feet long. You can also see the lower side of a typical "Tylosaur" snout, where the premaxillary that extends significantly beyond the first tooth row. It has been suggested that Tylosaurs may have used this bony snout as a ram. |

|

The two rows of pterygoid teeth on the hard palate are visible at the back of the mosasaur's mouth. These were another adaptation that allowed the mosasaur to catch and swallow struggling, slippery prey in the middle of the ocean.... not an easy feat (try bobbing for apples). |

|

This picture shows the head and fore-body of the mosasaur as it descends over the main entrance to the Museum of Natural History. (Imagine someone walking through the door, unaware, and looking up!) The jaws are filled with large (3-4 inch) conical teeth that were used by the mosasaur to seize its prey. Mosasaurs had rather unique jaw mechanisms, much like those of modern snakes, that allowed them to flex their lower jaws and swallow their prey whole. |

|

A picture of the massive skull from slightly above. |

|

Another shot from above. |

|

.... and a third view. |

|

This is the left front paddle of the mosasaur. Mosasaurs evolved from land dwelling reptiles that may have looked very similar to modern Monitor lizards. As they adapted to life in the sea, their limbs slowly changed into more useful paddles, becoming webbed and elongated. At some point, they would have lost their ability to walk on land, and spent their entire lives in the ocean. Interestingly (at least to me), their paddles never became the very rigid, almost solid bone structures found in Ichthyosaurs and Plesiosaurs. |

|

This picture shows the rear paddles and pelvis of the mosasaur. It appears that the hind limbs were becoming less and less useful as mosasaurs evolved, and would have eventually become vestigial like those of modern whales. The pelvis itself was no longer firmly attached to the vertebral column and could not have supported the weight of the animal on land. |

|

The right hind limb of the Bunker mosasaur, taken from the balcony above the main floor of the museum. |

|

A rather unusual shot of the pelvis and hind limbs of the mosasaur. Unlike land animals, the pelvic bones were not firmly anchored to the spinal column. This adaptation to life in the ocean would probably meant that mosasaurs could not have move well on land since their limbs would not have been able to support their massive bodies. |

|

Still chasing that "big one that got away", this photo shows the mosasaur in pursuit of a large Ichthyodectid fish, probably Xiphactinus audax. While fish probably made up a large portion of a mosasaur's diet, evidence shows that they were very opportunistic feeders, also dining on ammonites, pteranodons, birds, other mosasaurs, and even plesiosaurs. When you're the biggest and baddest in the pond, you get to call the shots. |

|

An inside (left) and outside view of the right quadrate (actual bone) of the Bunker Tylosaur (KUVP 5033). The scale is six inches and shows the quadrate to be over eight inches tall! (Photographed 8/16/99) |

|

A lingual (inside) view of the right coronoid, part of the right lower jaw.... simply huge. For more pictures of mosasaurs in museums around the world, take a look at the Virtual Mosasaur Museum. |

To see this spectacular fossil mount and many more Kansas fossils, visit the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History in Lawrence, Kansas:

Drawing of the Xiphactinus audax at the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History.

For more information about the work done by Triebold Paleontology, check out Mike Triebold's website: