MOSASAUR PATHOLOGY

"Even the big guys got no respect"

|

MOSASAUR PATHOLOGY "Even the big guys got no respect"

Copyright © 2001-2012 by Mike EverhartLast revised 07/15/2012 |

Mosasaurs were the largest predators in the shallow sea that covered Kansas during the Late Cretaceous. But being the top predator was no guarantee for survival, especially since they were living with giant sharks like Cretoxyrhina mantelli that were competing for the same prey, and always looking for a chance to feed on a sick or injured mosasaur. It was a dangerous place to live, especially for the younger, smaller mosasaurs. Mosasaurs lived for 20 or more years, and non-fatal injuries sometimes occurred during their lifetime. Records of these injuries are occasionally preserved in preserved in the fossil record.

| Gaudry wrote: "We have assembled 95 vertebrae in articulation

(26 lumbar, 67 caudal) for a total length of 3.74 meters; A drawing of the

specimen is provided in fig. 300. It doesn't belong to an old individual,

because none of the caudal vertebrae show a fusion of the haemal arch, as

shown in fig 298; however, one can see evidence of disease in the

vertebral column. Dr Fischer has diagnosed the infection as osteoperiostitis which, by consequence,

3 vertebrae, in one point, and 6 on another, have lost their intervertebral

cartilage and have fused. His observation has been confirmed by Dr.

Ranvier. This old case of palaeontological pathology is worth being

noticed. Everywhere life existed, there was also disease; the suffering of

a creature from the secondary era is one more uniting trait with today's creatures."

(Translation from the French by Jean-Michel Benoit)

Note that this specimen has since been re-identified as Plioplatecarpus (Mulder 2001; Bardet 2012) |

Professor Benjamin F. Mudge (1878) was one of the first American paleontologists to discuss mosasaur pathology. He had been collecting mosasaurs in western Kansas since the late 1860s and at the time had probably seen more mosasaur remains than anyone else.

Writing about the geology of Kansas in the U.S. Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories (Hayden, 1878), Mudge described several of the injuries he had seen in mosasaur bones. He noted (page 287) that "Sharks' teeth were sometimes found in the remains of food, showing the taste of the Saurians and their high carnivorous natures. On the other hand, we frequently found evidence that the sharks returned the compliment, for bones of Saurians were found with the marks of the sharp, serrate teeth of Galeocerdo, which could not have been made unless the bones were still fresh and unhardened. That such huge reptiles must have had fierce contests with each other is also apparent. The type of the head and teeth would indicate this. But in addition it was no uncommon thing to find Saurian ribs which had been broken and again united while the animal lived. In one case a more serious injury occurred. In a fine specimen, one of the most perfect collected by us, we discovered that the animal had received a very serious injury to his back, which he had outlived. Five of the vertebrae had been fractured so seriously as to lose many of the spinous processes, after which it had healed, but the whole had grown together (anchylosed) so as to lose the natural form of the separate bones and become a confused, firm mass. The enemy that could have thus injured a monster 35 or 40 feet in length, and whose jaws of defense were 33 inches long, must have made a fierce contest."

|

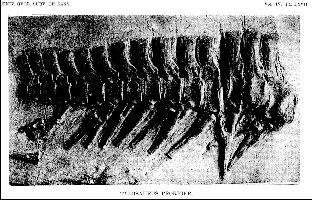

Williston (1898, p. 214) reported that “ I

have observed exostosial growth in the their lower jaws,

the vertebrae, especially those of the tail, and the paddles, especially

the digits. In some the mutilations have been extensive. One tail of Platecarpus

has the spines of the distal half of the tail broken off and false joints

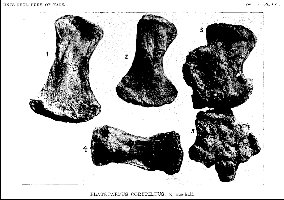

produced.” He also provided the first photographs of pathologic mosasaur

bone, including paddle elements (1898, Plate LVI) of a Platecarpus that exhibited exostosial growth, and a series of Tylosaurus

(KU 1013) caudal vertebrae (1898, Plate LXVII) that preserved

“ante-mortem injuries.”

LEFT: Plate LXVII from Williston 1898: "Terminal caudal vertebrae of Tylosaurus proriger, in matrix, continuation of those in plate LXVI, the proximal ones showing ante-mortem injuries." Note that image is reversed. (Recent photo of KUVP 1013 HERE) RIGHT: Plate LVI from Williston, 1898: "Figs. 1, 2, 4, femora of Platecarpus coryphaeus; fig. 3, radius; fig. 5, radius, carpus, and part of metacarpus, showing exostosial growth." (Later photos of KUVP 1172 from Moodie 1917 HERE ... 1918 HERE) |

|

Mudge's student and co-worker, S. W. Williston (1898, p. 214) noted, "That they [mosasaurs] were pugnacious in the extreme is very evident from the many scars and mutilations which they suffered during life. I have observed exostosial growth in their lower jaws, the vertebrae, especially those of the tail, and the paddles, especially the digits. In some the mutilations have been extensive. One tail of a Platecarpus has the spines of the distal half of the tail broken off and false joints produced. Never have I known a case where there has been evidence of ante-mortem loss of the tail, or any part of it. A paddle of another specimen, figured in part in plate LVI, has the bones of the forearm, carpus and metacarpals all united by exostosis." Williston was probably the first to photograph and publish an image of a pathology in mosasaur remains.

Williston (1904, p. 49) said "As

I have previously remarked, it is certain that all mosasaurs did not die of old

age. Indeed, the many hyperostosial mutilations of antemortem origin indicate

only too well the fierce struggles

the mosasaurs had with the carnivorous enemies of their own and other kinds.

Charles Sternberg (1909, p. 50), in his discussion of Tylosaurus proriger, suggested that "...many of the ankylosed bones which we fossil hunters often find in the chalk of the Niobrara Group of the Cretaceous were broken by blows from these ram-nosed lizards."

Later (1914, p. 161), Williston enlarged somewhat on his previous statement: "That the mosasaurs were pugnacious in life is conclusively proved by the many mutilations of their bones that have been observed, mutilations received during life and partly or wholly healed at the time of death. Bones of all vertebrates are repaired after injury by the growth of more or less spongy osseous material about the injured part, forming sort of a natural splint. This material is more or less entirely removed by absorption when it is no longer required for the support of the broken ends. Many such injured bones of the mosasaurs have been found; sometimes the bones of the hands and feet have grown together, and not infrequently the vertebrae have been found united by these osseous splints; occasionally even the skull itself, especially the jaws, attest extensive ante-mortem injuries. In a single instance the writer has observed the loss of a part of the tail, where it probably had been bitten off. It may be mentioned, however, that the bones of the tail had no such "breaking points" in the mosasaurs as have those of many land lizards, whereby a part or all may be lost as a result of even a trivial injury."

More evidence of healed injuries preserved on the remains of a mosasaur

One Bad Luck Mosasaur

Martin and Bell (1995) described two

examples of “club tailed” mosasaurs from the Pierre Shale of South Dakota.

One of the specimens, a juvenile Clidastes had seven caudal vertebrae fused

into a solid mass. The other was a plioplatecarpine (Tylosaurus or Plioplatecarpus)

which had three fused caudal vertebrae. They also reported that all of the

“club-tailed” mosasaurs they had seen were juveniles.

The specimen below most likely came from a juvenile Tylosaurus.

|

LEFT: At first glance, this pile of mosasaur caudal vertebrae

(FHSM VP-13750) appeared to be evidence of just another mosasaur tail bitten off by

a large shark and partially digested before being regurgitated. However, the odd shaped

lump of bone in the lower left turns out to be at least 3 and probably 4 caudal vertebrae

that have been fused together as the result of an infection. It appears likely that

the mosasaur had the end of it's tail bitten off by an unknown predator (probably a

shark). The wound became infected, fusing the vertebrae and more or less forming a bony

club at the end of the tail as it healed. The mosasaur survived the initial attack but

then was "sliced and diced" some time afterwards by a

large shark, most likely Cretoxyrhina.

RIGHT: Years later, additional preparation and a closer examination revealed the remains of a shark tooth (FHSM VP-17985) embedded in the fused "club" portion of the remains, direct evidence of the source of the infection. (Closer view here) |

|

"OUCH! That must have hurt!!!"

Below are photographs of the right side of the skull of a Tylosaurus proriger that I saw in an exhibit in a small museum in Hobetsu, Japan. The specimen (HMG-1288) had been discovered in the Smoky Hill Chalk of western Kansas and purchased by the museum for their exhibits. While the left side of the 1.2 m skull appears undamaged, the broken bones on the right side suggest that this mosasaur ran into something hard, like a rock.

(LEFT) A large area of damaged bone was visible on the right side of premaxilla and a fracture was evident in the suture between the premaxilla and right maxilla. The unusual 'humped' silhouette of the skull may indicate an additional fracture of the posterior extension of the premaxillae. (CENTER) This picture shows the extent of the damage to the suture between the right maxilla and the premaxilla, including the rearward displacement of the first tooth in the right maxilla. (RIGHT) The appearance of the bone in this picture appears to indicate that some healing had taken place before the mosasaur died. According to Gorden Bell (pers. comm., 2002), the snout of a mosasaur was very well equipped with nerve endings... and this sort of injury would have been extremely painful.

|

|

|

Rothschild and Martin (1987) discussed what appears to be evidence of avascular necrosis (the bends or decompression sickness) in the vertebrae of mosasaurs. If true, it means that mosasaurs were apparently not well adapted for deep diving.

|

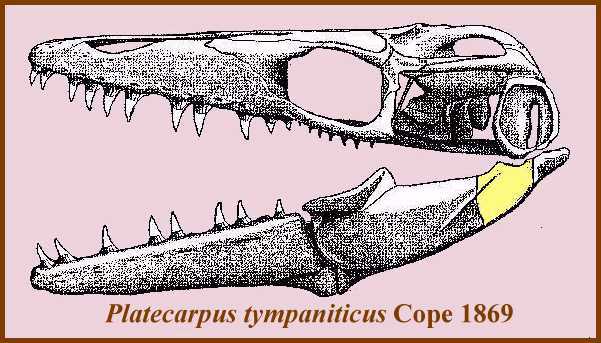

Below are several pictures of a fragment at the back of a mosasaurs left, lower jaw (surangular and articular). The breaks on both ends are fresh, but no other pieces were found. This bone fragment is the portion colored yellow in the drawing at left. In life, it served as the attachment (hinge) point between the left lower jaw and the quadrate at the back of the skull. There are three oblong holes in the outside surface (arrows) of this fragment that may not belong there. The two larger holes (2 x 3 mm) are connected by a larger cavity which is barely visible as a light spot in the largest blow-up. The smaller upper hole is rounder in shape and all three holes seem to angle somewhat downward rather than going straight into the bone. The edges of all three holes are smooth and there is no sign of a recent bite trauma that I can see. |

This isolated bone fragment was found in the lower Smoky Hill Chalk Member (late Coniacian) of the Niobrara Chalk in Gove County, Kansas. It probably came from an adult mosasaur (Platecarpus tympaniticus) that was 16-18 feet long. Bones preserved in the Smoky Hill Chalk Member frequently show marks from scavenging by sharks (mostly Squalicorax) but are very rarely, if ever, damaged by invertebrate borings. The openings look very similar to the unexplained holes in the back of both of the lower jaws of Sue, the Tyrannosaurus rex, but do not penetrate completely through the bone.

Now, the other side of the story.............

Credits: Platecarpus tympaniticus skull drawing adapted from: Russell, D. A., 1967. Systematics and morphology of American mosasaurs. Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, Bulletin 23.

References:

Bardet, N. 2012. The

mosasaur collection of the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle of Paris. Bull.

Soc. géol. France 183(1):35-53.

Dollo

L. 1882. Note sur l’ostéologie

des Mosasauridae. Bulletin du Musee

Royal d’histoire naturelle de Belgique 1(3):55-80, pls. IV-VI.

Dollo, L. 1892. Novelle note

sur l’osteologie des Mosasauriens. Bulletin de la Société Belge de Géologie,

de Paléontologie et d'Hydrologie 6:219-259, pl. III-IV.

Everhart, M.J. 2008. A bitten skull of Tylosaurus kansasensis (Squamata: Mosasauridae) and a review of mosasaur-on-mosasaur pathology in the fossil record. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 111(3/4):251-262.

Gaudry, A. 1890.

Les enchaînements du monde animal dans les temps géologiques:

Fossiles secondaires. Librairie

F. Savy, Paris, 323 pp.

Lindgren, J., Jagt, J.W.M., and Caldwell, M.W. 2007. A fishy mosasaur: the axial skeleton of Plotosaurus. Lethaia 40: 153-160.

Lingham-Soliar, T. 2004. Palaeopathology and injury in extinct mosasaurs (Lepidosauromorpha, Squamata) and implications for modern reptiles. Lethaia 37: 255-262.

Martin, L. D. and Rothschild, B.M. 1989. Paleopathology and diving mosasaurs. American Scientist 77:460-467.

Martin, J.E. and Bell, G.L. Jr. 1995. Abnormal caudal vertebrae of mosasauridae from Late Cretaceous marine deposits of South Dakota. Proceedings of the South Dakota Academy of Science 74:23-27.

Moodie, R.L. 1917. Studies in paleopathology. I. General consideration of the evidences of

pathological conditions found among fossil animals. Annals of Medical History 1:374‑393.Moodie, R.L. 1918. Paleontological evidence of the antiquity of disease. The Scientific Monthly 7:265-281.

Moodie, R.L. 1921. Status of our knowledge of Paleozoic pathology. Proceedings of the Paleontological Society, Bulletin of the Geological Society of America 32:321-325.

Moodie, R.L. 1923. The Antiquity of Disease. University of Chicago Press. 148pp.

Mudge, B.F. 1878. Geology of Kansas. Pages 60-63 in First Biennial Report of the Kansas State Board of Agriculture. Topeka.

Mulder E.W. 1985. Beenvliesontsteking: een oude kwaal! Natuurhistorisch

Maandblad 74(8):129-130.

Mulder E.W.A. 2001.

Co-ossified vertebrae of mosasaurs and cetaceans: implications for the mode of

locomotion of extinct marine reptiles. Paleobiology

27(4):724-734.

Rothschild, B. M. and Martin, L. 1987. Avascular necrosis: Occurrence in diving Cretaceous mosasaurs, Science, 236:75-77.

Rothschild, B. M. and Martin, L. 1993. Paleopathology: disease in the fossil record, CRC Press. (Chapters 19 and 21).

Russell, D.A. 1967. Systematics and morphology of American mosasaurs. Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, Bulletin 23, 241 pp.

Schulp, A.S., Walenkamp, G.H.I.M., Hofman, P.A. M., Rothschild, B. M. and Jagt, J.W. M. 2004. Rib fracture in Prognathodon saturator (Mosasauridae, Late Cretaceous). Netherlands Journal of Geosciences / Geologie en Mijnbouw 83(4): 251-254.

Shimada, K. 1997. Paleoecological relationships of the late Cretaceous lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli (Agassiz). Journal of Paleontology 71(5):926-933.

Sternberg, C.H. 1909. The Life of a Fossil Hunter. Henry Holt and Company, 286 pp.

Williston, S.W. 1898. Mosasaurs. The University Geological Survey of Kansas, Part V. 4:81-347, pls. 10-72. (Click here for some of the figures from this article)

Williston, S.W. 1914. Water reptiles of the past and present. Chicago Univ. Press. 251 pp.