PTERANODONS

FLYING REPTILES OF THE LATE CRETACEOUS

WESTERN INTERIOR SEA -

A Photographic Atlas

Copyright © 2000-2013 by Mike Everhart

|

PTERANODONSFLYING REPTILES OF THE LATE CRETACEOUS WESTERN INTERIOR SEA - A Photographic Atlas Copyright © 2000-2013 by Mike Everhart Updated 12/05/2014 |

|

Pterosaurs (flying

reptiles) were the first vertebrates to take wing and evolved during the Late Triassic.

They were superbly adapted for flight, with hollow, air-filled bones, a relatively large,

birdlike brain (Seeley, 1871; Edinger, 1927; Wellnhofer, 1991), and membranous wings that

were supported by the elongated fourth finger of each hand. In the much larger

pteranodons, their upper bodies were stiffened by rigidly binding the fused dorsal

vertebrae, ribs, scapulacoracoid and sternum together into a solid structure (notarium)

that supported the large muscles needed to power their wings. Some smaller pterosaurs were

apparently covered with “fur-like” bristles and it is likely that they were

"warm-blooded" to some extent. Besides the elongated

“wing-finger,” they had three clawed fingers

on each hand, and four clawed toes on each foot.

The smallest known pterosaur (Pterodactylus)

was about the size of an American robin, and one of the largest (Quetzalcoatlus)

had a wingspread as large as a light airplane (11-12 m/ 36-39 ft.).

Almost all of the known remains of Pteranodon come from the Smoky Hill Chalk of west Kansas. A few are found in the overlying Pierre Shale in Kansas, South Dakota and Wyoming. These are all marine deposits, as much as hundreds of miles from the nearest shoreline at the time. So what were these flying reptiles doing so far from land? The current idea is that they were feeding, but why fly that long distance just to feed? To me it seems far more likely that what we are seeing in these remains are those pterosaurs that died during migrations across the seaway, going to and from the rookeries where their young were born / hatched and raised. Modern bird migrations, especially those over water, tend to lose weak, sick or old individuals. Such losses would also occur among pterosaurs. LEFT: A flight of Pteranodon longiceps as shown in the opening scenes of the National Geographic IMAX movie, "Sea Monsters" (Released October, 2007). I was fortunate to be one of the senior science advisers on the movie, along with Ken Carpenter, Glenn Storrs, Larry Martin and others. |

| PTEROSAUR NEWS AND VIEWS:

New specimen: Pterodactyl mother found with egg in China - color photos - Lü, J., Unwin, D.M., Deeming, D.C., Jin, X., Liu, Y. and Ji, Q. 2011. An egg-adult association, gender, and reproduction in pterosaurs. Science 331(6015):321-324. (January 21, 2011) Pterosaur Blog - Updates on pterosaur discoveries around the world. Gwawinapterus - A new

pterosaur from Canada - Arbour,

V. M. and Currie, P.J.(2011. An istiodactylid pterosaur from the Upper

Cretaceous Nanaimo Group, Unfortunately it turned out to be a fish: Vullo, R., Buffetaut, E. and Everhart, M.J. 2012. Reappraisal of Gwawinapterus beardi from the Late Cretaceous of Canada: A saurodontid fish, not a pterosaur. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 32(5):1198-1201. Two new Pteranodon species named: Kellner,

A.W.A. 2010. Comments on the Pteranodontidae (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea)

with description of two new species. Anais da Academa Brasileira de Ciências

82(4):1063-1084. |

|

Pteranodon

( meaning "wing without tooth") were a group of Late Cretaceous

flying reptiles that were characteristically toothless and tail-less (they did have short

tails). The males grew to large size (wingspreads of 7.5 m (25 ft) or more) during

the deposition of the Smoky Hill Chalk (87-82 mya), and were even larger near the end of

the Late Cretaceous. The

largest individuals discovered so far in Kansas had a wingspread of about 8 m (26 ft.) but

by some estimates may have weighed no more than 11 kg (25 lb). However,

in a recent article in the Journal of Vertebrate

Paleontology, Henderson (2010) estimated the mass of a Pteranodon

longiceps with a 5.34 m (17.5 ft) wingspread at 18.6 kg (41 lb).

Clearly, there is still work to be done on their anatomy and

physiology.

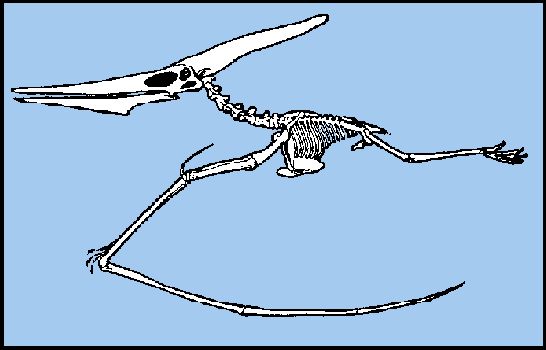

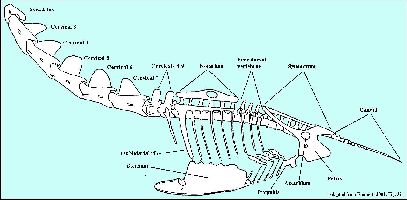

Compared to the size of their heads and wings, their bodies are almost absurdly small. One comparison provided by Hankin and Watson (1914) was that "with a body little larger than that of a cat, they had a span of wing asserted in some cases to have reached 21 feet or more!" LEFT: The skeleton of Pteranodon longiceps (lateral view) - Adapted from original drawing by Eaton (1910). CLICK FOR LARGER VERSION |

Systematic Paleontology Order Pterosauria Suborder Pterodactyloidea Superfamily Ornithocheiroidea Family Pteranodontidae Genus Pteranodon Marsh 1876 Type Species Pteranodon longiceps Marsh 1876 |

During the summer and fall of 1870, O. C. Marsh and his Yale scientific expedition collected fossils from as far west as Wyoming and Utah. Late in November, they made a brief visit to western Kansas in the vicinity of Fort Wallace where he was assigned a military escort. The weather was cold but they were still able to collect very successfully for several days along the Smoky Hill River in what are now Wallace and Logan counties. In a short note published after returning to Yale in mid-December, Marsh (1871) noted only that "some interesting reptilian and fish remains" were collected during their two-week stay in Kansas.

In his first mention of a North American pterosaur, Marsh (1871) reported that the distal ends of two long bones (two metacarpals from the wings of two individuals (YPM 1160 and 1161) had been found, and noted that they were not unlike those from Europe figured by Richard Owen in 1851. Marsh (1871, p. 472) also noted that the bones were thin-walled and hollow. From these few fragments, he named a new species Pterodactylus Oweni, "in honor of Professor Richard Owen of London." Marsh estimated the size of the creature from the fragments and noted that the outstretched wings would have measured "not less than twenty feet!" ... a very accurate estimate considering that nothing like this had ever been seen before.

Surprisingly, and as a complete fabrication since no skull material was reported to be present, Marsh also indicated that "the teeth are smooth, and compressed." In his much more complete description of additional remains of this and two other species collected by the 1871 expedition, Marsh (1872, p. 244) again noted the presence of teeth in Pteranodon: "The teeth found with remains of this species, and supposed to belong to them, are very similar to the teeth of Pterodactyls from the Cretaceous of England. They are smooth, compressed, elliptical in transverse outline, pointed at the apex and somewhat curved." Of the teeth of a second species (Pterodactylus ingens), Marsh wrote (ibid., p. 247) that "the dental characters of this species are at present only known from a single crown of a tooth; found with one series of the specimens and from two larger and very perfect teeth found by themselves, which agree so closely with the former that they deserve notice in this connection. These specimens are less curved and less compressed than the teeth referred to Pt. occidentalis, but in other respects they are nearly identical." According to Chris Bennett (pers. comm. 2003), the teeth collected by Marsh in association with his initial Pteranodon wing bones were fish teeth, probably those of an Ichthyodectes, and are still curated in the Yale Peabody collection.

Marsh, however, apparently assumed that his American "Pterodactyle" would have teeth like its European cousins and was hedging his bet on their discovery when the first skull was found. In that regard, he was not the only one who would be playing "fast and loose" with this conclusion. His rival E. D. Cope (1872, p. 337) also indicated, slightly more conservatively, that Pteranodonskulls "were slender and the teeth indicated carnivorous habits." As shown in an illustration in a book called Buffalo Land (Webb, 1872), however, it is clear that Cope believed that at least one of the species he had named (Ornithochirus umbrosus) had teeth.

In the summer of 1871, Marsh and the second Yale scientific expedition returned to Kansas. Marsh was able to return to the spot where he had found the first remains of a Pteranodon, and he located additional pieces of the same bone. By the time Marsh (1872) published more complete descriptions, however, the giant Pteranodonswere already taking a back seat to the recent discovery of toothed birds in western Kansas. Marsh noted that the name he gave to the first specimen (Pterodactylus Oweni) was preoccupied by a specimen described by Seeley and replaced it with the name Pterodactylus occidentalis. Besides this species, Marsh (1872, p. 246-247) collected several specimens of "the most gigantic of Pterosaurs," which he called P. ingens(YPM 1160 and 1172) and estimated had a wingspread "of nearly 22 feet!" Marsh also named another, smaller species (P. velox; YPM 1176) that was found in 1871 on the basis of what he believed were differences he saw in the wing bones.

Bennett (1994) examined the Marsh collection at the Yale Peabody Museum and indicated that because of the stratigraphic level in which the pterosaur remains collected by Marsh in 1871 and 1872 occurred, they were all probably Pteranodon longiceps. In that regard, Bennett (1994, p. 14) considered all the early names given by Marsh and Cope to be nomen dubia because the material does not exhibit any species-specific characters and was too fragmentary to be accurately identified beyond the genus Pteranodon.

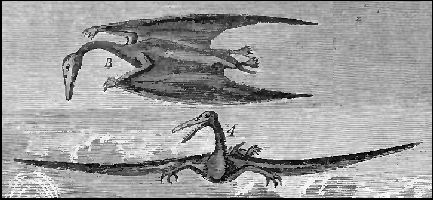

Cope apparently found at least two sets of Pteranodonremains during his trip to Kansas in late 1871. In a short note, Cope (1872a, p. 337) named two species, Ornithochirus umbrosus (AMNH 1571) and O. harpyia (AMNH 1572), that were apparently distinguished from one another only on the basis of size. In doing so, he accepted Seeley's name for the genus and apparently ignored Marsh's Pterodactyluswithout further comment. In a narrative that preceded the listing of the two new species, Cope (ibid., p. 323) described them in their natural habitat: "The flying saurians are pretty well known from the descriptions of European authors. Our Mesozoic periods had been thought to have lacked these singular forms until Professor Marsh and the writer discovered remains of species in the Kansas chalk. Though these are not numerous, their size was formidable. One of them, Ornithochirus harpyia Cope, spread eighteen feet between the tips of its wings, while the O. umbrosus Cope, covered nearly twenty-five feet with his expanse. These strange creatures flapped their leathery wings over the waves, and often plunging, seized many an unsuspecting fish; or, soaring, at a safe distance, viewed the sports and combats of the more powerful saurians of the sea. At night-fall, we may imagine them trooping to the shore, and suspending themselves to the cliffs by the claw-bearing fingers of their wing-limbs."

While this image of pteranodons hanging from rocks along the seashore has been shown in numerous recreations over the years, it is probably just a fantasy. As noted by Stein (1975), it would have been impossible for Pteranodon to land on all fours on level ground without collapsing the wings first and thus losing lift. Performing such a landing against the vertical wall of a cliff would seem to be a death-defying act. Furthermore, none of the cores of the wing claws (unguals) I have collected or examined show any damage on the tips as might be expected from a daily routine of hanging from one's fingertips.

|

The first Pteranodon specimens found in North America

were discovered in the Smoky Hill Chalk of western Kansas by O.C.

Marsh in 1870. The remains he collected consisted only of fragments of the long

wing bones. However, they were readily comparable (though much larger) with

pterodactyl remains from the Jurassic of Europe.

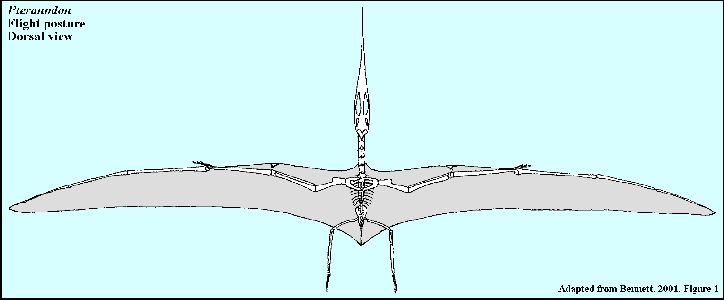

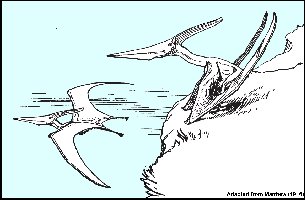

The only pterosaurs that are currently known to occur in the Smoky Hill Chalk are the highly developed pteranodons, including P. longiceps, P. sternbergi, Nyctosaurus gracilis and N. nanus. These flying reptiles do not have teeth or long tails like the earlier pterosaurs found in the Jurassic of Europe, and are generally much larger. LEFT: The current version of the skeleton of Pteranodon longiceps in flight (wingspread about 20 feet) - upper Smoky Hill Chalk, Kansas. The wing membranes are narrower than in earlier reconstructions and are no longer considered to have been connected to the lower legs. (Adapted from Bennett, 2001). This is more consistent with the wings of modern long distance flyers like the albatross and frigate bird. |

Pterosaurs were apparently "warm blooded" in some respects, and may have had a thin covering of hair on their bodies. Their role in the Late Cretaceous Inland Sea was probably similar to modern sea birds such as the albatross and pelican, and they may have spent most of their lives soaring over the ocean looking for food. While they apparently fed primarily on fish and other small marine organisms, we are not sure how they fed. It is unlikely that they were "skimmers," that is, taking fish from the ocean surface while in flight.

Pteranodon longiceps

Pteranodons were first discovered in the upper chalk near Fort Wallace in Logan County, Kansas by O.C. Marsh in 1870. The only remains collected initially were the fragments of long wing bones, but they were recognizable as being similar to those of the Jurassic pterodactyls found in Europe. Marsh initially named two species from the remains, Pterodactylus occidentalis and P. ingens, now considered by Bennett to be nomen dubium. Pteranodon. longiceps Marsh (1876) was named from a much more complete specimen (YPM 1177) collected by S.W. Williston that included the skull. Cope also named two species from specimens that he collected in 1871 (Ornithochirus umbrosus and O. harpyia / occidentalis). It was later noted by Bennett (1994) that all of these early specimens were collected from the upper chalk and were probably from the same species, P. longiceps.

|

At first, both Marsh (1871) and Cope (1872) contended that these giant

flying reptiles also had teeth like their Jurassic cousins. In Marsh's case, it was

because of some fish teeth that were found near the bones; Cope apparently just decided

that they probably had teeth. It wasn't until 1876 with the discovery of the skull of

the type specimen of Pteranodon longiceps (YPM 1177) by S.W. Williston in

the upper chalk of western Gove County that it was discovered that these flying reptiles did

NOT have teeth and, and subsequently the genus name, Pterodactylus, was

changed to Pteranodon by Marsh (1876).

LEFT: Two reconstructions of Ornithochirus umbrosus Cope 1872 (Adapted from a plate opposite page 356 in Webb's 1872 Buffalo Land), most likely drawn from instructions provided by E.D. Cope. Note that neither pteranodon has a crest (unknown in 1872) and the lower figure (4) has teeth (assumed). |

|

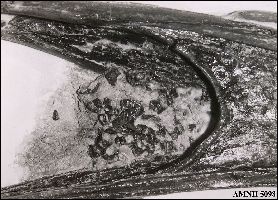

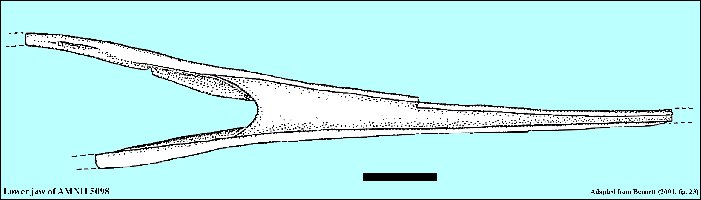

LEFT: Dorsal view

of the posterior portion of the lower jaws of AMNH 5098, collected by Charles H. Sternberg in 1877 in Lane County, showing the mass of small fish

vertebrae. Bennett (2001, pers. comm, 2004) indicated that the fish remains were probably

stomach contents regurgitated when the Pteranodon died.

RIGHT: A drawing of the jaw of AMN5098 adapted from Bennett (2001, fig. 23). Click for a photo of the complete specimen (adapted from Wellnhofer, 1991) |

|

WHAT DID PTERANODON EAT?: It seems likely that Pteranodon fed on fish. Although not unexpected, actual evidence has been somewhat lacking. Williston (1891, p. 1126) reported finding preserved gut contents in the remains of a Pteranodon: "“Several coprolites found within the above-described pelvis, ellipsoidal in shape, and about the size of an almond, showed bones so finely comminuted that their precise character could not be made out.” These masses most likely contained the bones of small fish, but even Williston was reluctant to identify them. In his article about "Flying Reptiles" in Natural History, Barnum Brown (1943, p. 106) described the specimen shown above (AMNH 5098) and noted that it contained the "backbones of two species of fishes..." Carpenter (1996) reported a Pteranodon specimen (UCM 45062) from the Pierre Shale in Wyoming that was associated with two small coprolites containing fish bones. Hargrave (2007) reported two specimens of Pteranodon (SDSM 45719 and 69040) from the Sharon Springs Member of the Pierre Shale of South Dakota that were collected in association with fish (Enchodus) vertebrae. Beyond these two examples, direct evidence of the diet of Pteranodon has not been forthcoming.

|

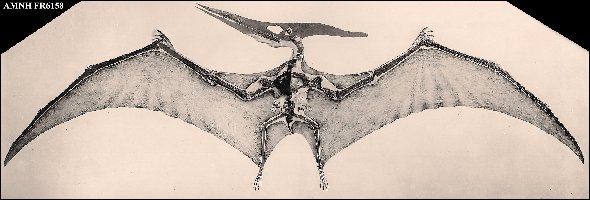

LEFT: AMNH FR6158 - A 1950s vintage picture of the reconstructed Pteranodon exhibit specimen at the American Museum of Natural History. The current exhibit does not include the wing

membrane. The specimen was found by H.T. Martin in 1916. It measures about 16 feet

from wingtip to wingtip.

RIGHT: Two male Pteranodon longiceps take to the air in this drawing adapted from a 1916 article by W.D. Matthew in the American Museum Journal. |

|

|

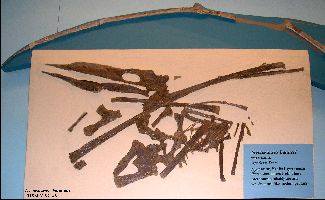

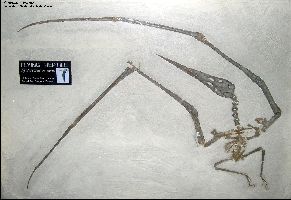

LEFT: The partial skull and skeleton of a Pteranodon collected by Charles H. Sternberg in 1918 from "12 miles south of Russell Springs in

Logan County, Kansas." The specimen was sold to Professor C. Wiman,

Upsala

University, Upsala, Sweden. The figure is adapted from a photograph of the slab mount

(Plate II) in Wiman (1920). Wiman noted that, contrary to Eaton (1910), Pteranodon does have a fibula (see arrow). Note that Williston (1891) had questioned the

presence of a fibula in Pteranodon, but later (1910) agreed that it did exist. REFERENCE:

Wiman, C. 1920. Some reptiles from the Niobrara Group in Kansas. Bulletin of the

Geological Institution of the University of Upsala, Uppsala, 18:9-18. See also: Mateer, N.J. 1975. A study of Pteranodon. Bulletin of the Geological Institutions of Uppsala 6:23-33.

RIGHT: Pages 9 and 10 from Wiman (1920). It is interesting to note that Ward's Natural History Establishment of Rochester, New York, arranged the sale of the specimen to Wiman. |

|

|

"TO BEAK OR NOT TO BEAK, THAT IS THE

QUESTION"

(With apologies to William Shakespeare)

Almost all other species of pterosaurs have teeth.... but Pteranodon,Nyctosaurus, Quetzalcoatlus, and a few other genera were toothless (edentulous). Did they have a horny beak like bird, such as is shown in most reconstructions?.... Good question... There is no fossil evidence for a beak, but a keratin sheath is unlikely to have been preserved except under the most favorable conditions. Here's what has been said to date on the subject:

In Marsh’s (1876, p. 1) report on the skull of Pteranodon longiceps, he says, “There are no teeth, or sockets for teeth, in any part of the upper jaws, and the premaxillary shows some indications of having been encased in a horny covering.”

However, Williston (1893, p. 2) notes that “There are no indications whatever of a horny sheath enclosing the jaw, and it is improbable that the covering of these parts was essentially different from that in the slender jawed Pterodactylidæ. In texture, the maxillaries are fine-grained, and wholly without the vascular foramina found in the corresponding bones of birds. The bones are composed of two thin and firm plates, separated by cavities which are bounded by irregular walls of bony tissue. In compression from which all Pterodactyl bones have suffered more or less, the greater resistance of those walls has cased irregularities upon the outer and inner surfaces. At the borders of the bones, where the thickness has been greater, the roughening is not observed.”

Eaton (1910, p. 3) states that “The margins of the jaws are smooth and thin, though not especially sharp, and no remains of horn sheaths have been observed.”

Bennett (2001, p. 10) notes that “The marginal ridges of the upper and lower jaws appear to have aligned with one another to provide a firm grip on prey items. The marginal ridges were probably covered by a horny sheath, but there is no direct evidence of this. There are no sulci for blood vessels such as are seen in the jaws of birds, turtles and some pterosaurs (e.g., Dsungaripterus, Young 1964, fig. 2). He also adds (2001, p. 32) that in one specimen (UNC 7), "the tip of the dentary is preserved and tapers to a point less than 1 mm in diameter."

All seem to agree that the bony tips of the upper and lower jaws extended to a sharp point... but no one seems to know what, if anything, that may have covered the bone besides a layer of epithelial tissue and possibly a thin layer of keratin. This seems like a rather fragile arrangement for a large animal, especially in view of the fact that few, if any injuries (pathologies) have been observed in tips of Pteranodonjaws. It certainly casts a doubt on Pteranodon "skim feeding" as they flew over the surface of the ocean. So, how were they feeding?

At this point, the jury is still out... and the question (above) remains open.

| Although I had collected scraps of Pteranodon bones on several occasions in the late 1980s, none of these specimens were readily identifiable. In 1990, however, things started to change. |

|

LEFT: In May, 1990, I came across some bone fragments eroding from

the chalk in Lane County. After clearing away some of the over burden, I found a complete

lower jaw of a Pteranodon sternbergi setting upright in the chalk. It had been

covered with plant roots and is extremely fragile, but I managed to recover it intact.

This was my specimen EPC1990-40. It has been donated to the Sternberg

Museum and is now FHSM VP-17702.

RIGHT: The following month I went back to the site and continued the dig, finding the sternum and the bones of a more or less complete wing. Click here for a closer view of the metacarpal IV and phalanx I. The specimen also included the sternum, vertebrae, and some leg bones. Based on the work done by Bennett (1992), I determined that this individual would have had a wing span of 4.7 m and was probably a sub-adult male. |

|

|

LEFT: The tip of the lower jaw of FHSM VP-17702 in dorsal and

ventral view (Scale = mm). It only took me 19 years to get around to cleaning it! The bone was covered with a mixture of chalk,

roots and preservative. Surprisingly, this little piece of bone is pretty tough and

was reasonably easy to prepare under a dissecting scope. So far as I am aware, there are

no other pictures of the tip of a Pteranodon lower jaw anywhere near this scale.

RIGHT: The extreme tip of the lower jaw in lateral view. Although it appears to go to a sharp point in dorsal and ventral view, it actually flattens out to a straight, "screwdriver"-like edge in lateral view. |

|

|

LEFT: A very nice Pteranodon skull and part of the

post-cranial skeleton (USNM 12167) collected by G.F. Sternberg from southeast of Elkader

in western Gove County in early 1931 (GFS 9-31). His description reads: "A nearly complete skull with lower jaws in place. Right side up,

the end of both beaks about three inches were destroyed by plant roots and cracks; the

crest is very fragile but almost all present. Length of the skull from back of the crest

to tips of beaks two feet and five inches. From back of the crest to where the distal end

is broken off is two feet and two inches. There are

seven large vertebrae which leave the skull and lay somewhat scattered, then there seems

to be several smaller vertebrae. There are wing and limb bones. Parts of the pelvic arch

and a number of broken and damaged small bones likely the feet."

The scale (10cm) is approximate but is based on data published by Bennett (2001) for this specimen. The length of the humerus ('L' shaped bone at center) is 168 mm. According to Bennett (1992), this would be near the average size of a female Pteranodon humerus. The specimen is currently on exhibit in the Smithsonian (USNM) in Washington, D.C. Another photo here |

|

LEFT: The skull and lower jaws of a female Pteranodon

sternbergi (CMNFV 41358) on display in the Canadian Museum of Nature, Ottawa, Canada.

It was collected by Mike Triebold in 1991 from Lane County, Kansas. It is the most

complete known Pteranodon skeleton and serves as the basis for various museum

displays, like this one in the Denver Museum

of Nature and Science. Wingspan is 11 feet (3.35 meters). Photo by Steve Cumbaa.

RIGHT: A life-reconstruction based on the same skeleton (CMNFV 41358) as displayed in the Rocky Mountain Dinosaur Resource Center, Woodland Park, Colorado. |

|

|

LEFT: The posterior portion of a Pteranodon skull (KUVP

2216 (old 976)) in right oblique view collected in Logan County by Charles H. Sternberg. This well preserved specimen is only partially

crushed and shows the palate as well as the occipital condyle in this view. Note that

the right quadrate and the quadratojugal are missing, but that the left quadratojugal and

condyloid process are complete.

RIGHT: The skull of KUVP 2216 in left oblique view showing the location of the orbit for the left eye and the base of the broken crest. A reconstruction of this skull was published by Williston: Williston, S. W. 1896. On the skull of Ornithostoma. Kansas University Quarterly 4(4):195-197, pl. I. |

|

Post-cranial Skeleton

|

LEFT: Partial skull, cervical vertebrae and sternum of a female Pteranodon

longiceps (FHSM VP-2183) in right lateral view. Note the small bones of the scleral

ring above the skull. This fairly complete specimen was collected by G.F. Sternberg

near Elkader in Logan County, and described by H.W. Miller in 1971. The specimen was

somewhat unique in that it was the first P. longiceps to be described from both

cranial and post-cranial material (Marsh's holotype - YPM 1177 was a partial skull and

other fragments).

RIGHT: Axial skeleton of Pteranodon in left lateral view (Adapted from Bennett, 2001, fig. 32). Note that while the neck is fairly flexible, the most of the rest of the vertebrae are fused together into the notarium and the synsacrum to provide a solid base for anchoring the wings and wing muscles. For clarity, the scapulo-coracoids are not shown in this figure. As reported recently by Claessens, et al. (2009), pterosaurs used a "skeletal breathing pump" in their highly efficient respiratory system. |

|

|

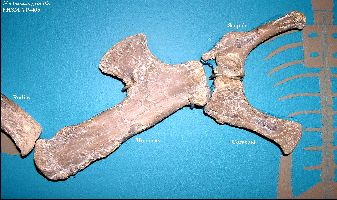

LEFT: The left scapulocoracoid of FHSM VP-2070 as viewed from

behind. This bone represents the fusion of the scapula and coracoid. The scapula portion

is attached to the vertebral column and the coracoid portion is attached to the sternum to

form a strong structural support for the wings. Specimen collected by M.C. Bonner in 1958

south of Russell Springs in Logan County. The right

scapulocoracoid of FHSM VP-2142 as viewed from the front. (Specimen collected by G.B.

Pierce in 1950 from near Gove in Gove County).

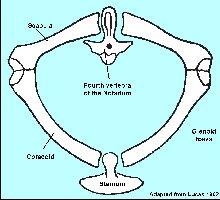

RIGHT: An anterior view of the pectoral girdle of Pteranodon, adapted from Lucas (1902). So far as I am aware, pterosaurs are the only vertebrate group where the scapula is actually attached to the vertebral column. |

|

|

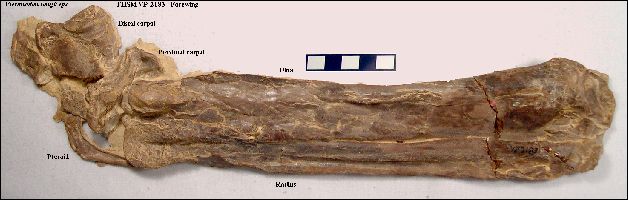

LEFT: The radius, ulna and pteroid bones of FHSM VP-2183. The pteroid bone was once considered to be the 'thumb' (e.g. Digit I) in pterosaurs. The two other pieces of bone in the upper left of the photo are the proximal and distal syncarpals (wrist bones) that would connect to metacarpal IV. Specimen collected by G.F. Sternberg in 1958 near WaKeeney in Trego County. Another specimen (FHSM VP-2072) is shown here in the plaster jacket used to recover it in the field. |

|

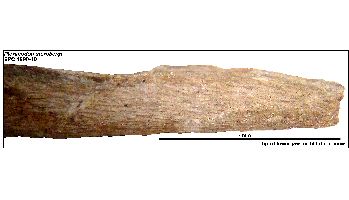

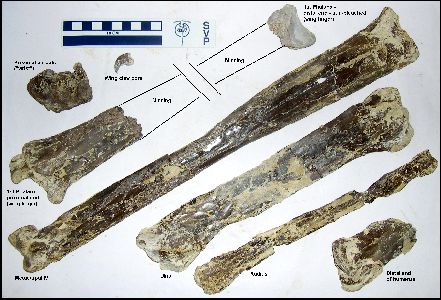

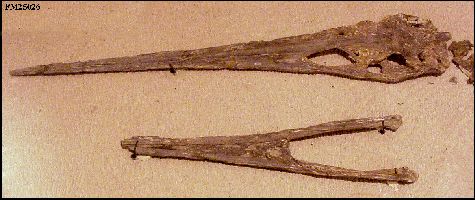

LEFT: The very large 1st wing phalanx (top) and 2nd wing phalanx

of FHSM VP-2064. The first wing phalanx is the longest bone in the pteranodon's wing.

Collected by G.F. Sternberg in 1953 near Moreland, Kansas (Graham County). The length of

the 1st phalanx is 60.6 cm and the length of the 2nd phalanx is 48.5 cm.

Note that according to Bennett (2001), another FHSM specimen (VP-184) is actually larger (65.3 cm and 54.9 cm, respectively; collected by G.F. Sternberg in 1949)... but the record holder at this point is probably the YPM 2833 specimen... WP1 = 69.2 cm; WP2 = 54.5 cm (est.). Figures provided by Bennett (1994) suggest that the length of WP1 is about 11% of the total wingspan of a Pteranodon. Using that figure, the wingspan of YPM 2833 would be about 7.6 m or just short of 25 feet! A very large male.... |

|

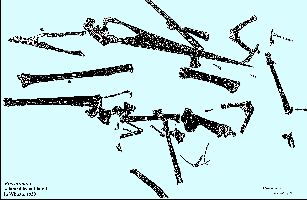

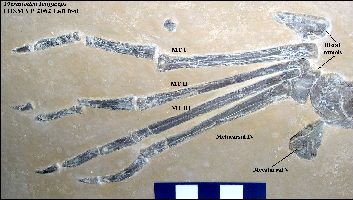

LEFT: Wing fingers (metacarpals) and claw cores (unguals) from a nearly

complete but headless specimen of Pteranodon sp. (FHSM VP-2062) in the Sternberg

Museum of Natural History. The specimen was found by George F. Sternberg in

September, 1956, northwest of WaKeeney, in Trego County. Without the skull, we cannot

determine for certain whether this specimen represents P. sternbergi or P.

longiceps since the post-cranial material is non-diagnostic between these

two species (Bennett, 1992). However, it is most likely P. longiceps since it

occurred in the upper chalk.

RIGHT: Wing fingers and claw cores from KUVP 49400, collected from Gove County by J.D. Stewart. This specimen is figured by Bennett (2001, Fig. 93). |

|

|

LEFT: Wing bones of a Pteranodon sp. that I discovered

in June, 2008 in the lower Smoky Hill Chalk, Gove County, KS. The long bone across

the center of the photo is Metacarpal IV (see drawing above) and is 18 inches (46 cm) in

length. Based on the length of this bone, I estimate that the wing spread of this

pteranodon was about 16 feet. This is somewhat larger than the average female Pteranodon (see Bennett, 1992), so I suspect it was a sub-adult male. Bones recovered so far are shown in yellow.

RIGHT: Proximal and distal views of the left proximal syncarpal of the wing. In Pteranodon, the "wrist" is made up of a pair of fused bones, the proximal and distal syncarpals, which set "back to back" between the radius and ulna, and the large metacarpal IV. The proximal syncarpal articulates with the distal ends of the ulna and radius. The distal syncarpal (not shown) articulates with the proximal end of metacarpal IV (Thanks to Chris Bennett for his help here). |

|

|

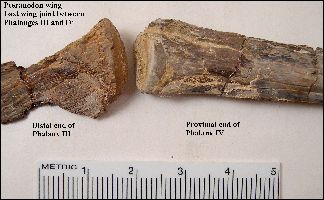

LEFT: Most Pteranodon remains that are collected are

fragmentary elements of the wings. EPC1990-42 was surface collected (weathered to a light

blue-gray) and represents the joint between the distal end of Metacarpal IV and the

proximal end of Phalanx I.

RIGHT: This is an unusual specimen (EPC1990-48) in that represents the end of a wing-finger.... the joint between Phalanx III an Phalanx IV. Click here for a look at the whole specimen. Note that Phalanx IV tapers to a sharp point. |

|

|

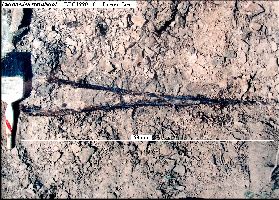

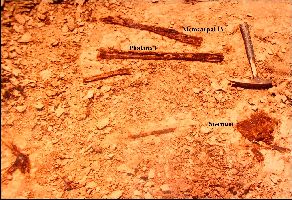

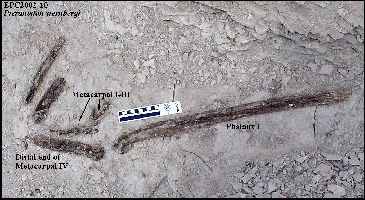

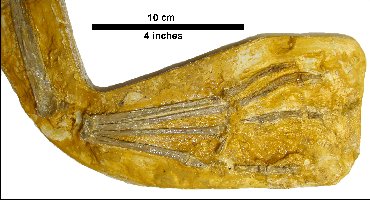

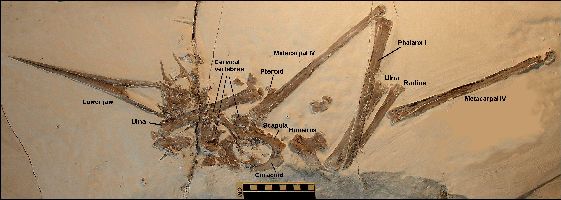

LEFT: A field photo of a partial Pteranodon sternbergi wing (EPC2002-10) as exposed in the lower Smoky Hill Chalk of southeastern Gove County.

The specimen shown in the picture, though badly damaged by roots, preserves a complete

phalanx I, a portion of metacarpal IV, and metacarpals I-III, plus some of the

tendons associated with MC I-III.

RIGHT: Some of the smaller pieces of EPC2002-10 that were recovered as float. The fragments include one of the carpals, four dorsal vertebrae, the head of one femur and various fragments (joint ends) of wing bones. A single Squalicorax sp. shark tooth was also associated with the specimen. Click here for a close-up view of the dorsal vertebrae. |

|

|

LEFT: The pelvis of a male Pteranodon (FHSM VP-2062) in

left lateral view as shown in the exhibits of the Sternberg Museum of Natural History.

Specimen collected by G.F. Sternberg from Trego County in 1956.

RIGHT: The relatively uncrushed pelvis of a nominal female Pteranodon (KUVP 993; Bennett, 1992, fig.6A) from Gove County in ventral right oblique view showing a relatively large pelvic opening (Anterior to the right). A photo of the same pelvis in dorsal, left oblique view, showing the acetabulum (socket) for the head of the femur.. |

|

|

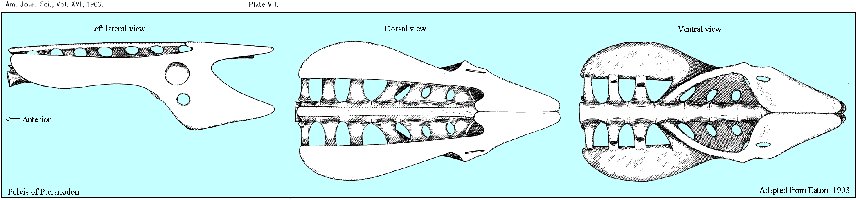

LEFT: Three views (left lateral, dorsal and ventral) of the pelvis of Pteranodon, adapted from G.F. Eaton (1903, Plate VII). |

|

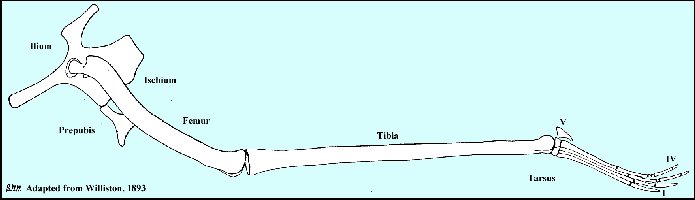

LEFT: One of the first drawings of a complete Pteranodon leg and hip (adapted from Williston, 1893). |

|

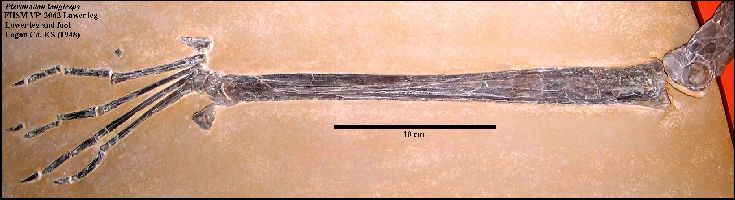

LEFT: Left lower leg (tibiotarsus) and foot of Pteranodon longiceps

(FHSM VP-2062). The tibiotarsus is 27.8 cm in length.

RIGHT: A closer view of the left foot of FHSM VP-2062. |

|

|

LEFT: The foot of a recently discovered (2011)

specimen of Pteranodon longiceps from the upper chalk of Gove

County, KS - FHSM VP-17997.

RIGHT: The upper tarsal bones of the foot of KUVP 27827. |

|

|

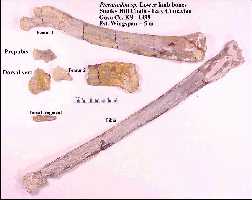

LEFT: Photos (2003) of the bones of the right leg of a lower chalk

(MU5) Pteranodon that I collected in 1999 and identified by Chris Bennett. The remains

were discovered by Johan Lindgren. The femur is 22 cm in

length and the tibiotarsus is 30 cm in length.

RIGHT: After some additional preparation and examination, I was able to assemble the complete right femur, and identify the distal end of the left femur, the acetabulum of the hip and a dorsal vertebra. |

|

|

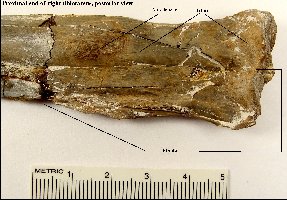

LEFT: The distal end of the right femur shows a very

distinct muscle scar.... most likely the attachment point of the caudofemoralis.

(2003 photo)

RIGHT: Close up (2010 photo) of the same bone, showing the large muscle scar. According to Bennett's 1992 analysis of Pteranodon bones, an average male with a 5.6 m wingspread would has a femur length of 25.0 cm and a tibia length of 32.8 cm while the measurement for a medial female would be 16.4 cm and 24.3 cm respectively. Although there are no characteristics in these bones themselves to distinguish male from female, their size would suggest that these bones were from an older female or a sub-adult male. Pteranodon leg bones are relatively rare as fossils. |

|

|

2010 photos:

LEFT: The right leg of Pteranodon sternbergi in posterior view. RIGHT: A close-up of the proximal end of the right tibiotarsus in posterior view showing the location of the fibula. |

|

Pteranodon sternbergi Harksen

Click HERE to see a Pteranodon sternbergi dig in western Kansas

A large pterosaur, with an adult male wing spread of more than 20 feet which ischaracterized by a large, upward pointing crest. As currently recognized, P. sternbergi is found fairly commonly in the lower Smoky Hill Chalk. The skull of the type specimen was collected by G. F. Sternberg in 1952 along the Solomon River near Bogue in Graham County, KS. Pteranodon sternbergiremains first occur in the lower Smoky Hill Chalk near Hattin's marker unit 5. P. longiceps is a closely related species that occurs higher (Middle Santonian) in the chalk.

Note here that Kellner (2010) considers Pteranodon sternbergito be distinct enough from P. longiceps that it should be in its own genus, and has revived Geosternbergia (see Miller 1978). In that case, the specimen should be referred to Geosternbergia sternbergi. I am doubtful that his suggestion will be accepted. So far as I am aware there are no other Pteranodon specimens known that preserve this unusual crest. This suggests to me that the crest may, in fact, be malformed and the result of a pathology (tumor or injury) during the life of the individual.

|

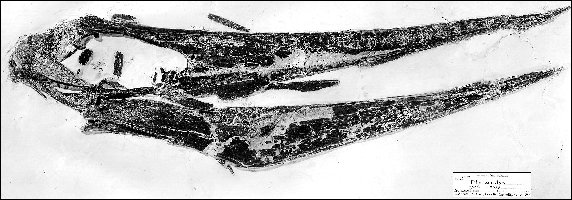

LEFT: A detail of the photo above showing the skull of UALVP 24238 which is missing the crest and the anterior portion of the beak. |

|

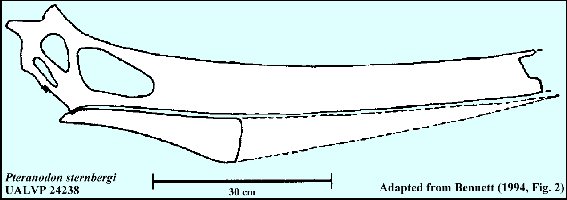

LEFT: A drawing of a partial skull of Pteranodon sternbergi (UALVP 24238; adapted from Bennett, 1994, fig. 2) in right lateral view. Although

the skull does not preserve a crest, Bennett described certain features that set it apart

from P. longiceps.

A similarly shaped (appearing to be non-tapering) upper beak (KUVP 967) is in the collection of the University of Kansas and can be viewed HERE. I suspect that the non--tapering appearance is an artifact of being crushed during preservation. |

|

LEFT: AMNH FR7515 is a nearly complete skull (missing back of the

skull and upper portion of the orbit) collected by Schaeffer and Sorenson from the Smoky

Hill Chalk (MU8-9, middle Santonian) on the Andrew Bird Ranch in Gove County, May, 1952.

Specimen as exhibited is about 76.4 cm (30 in) long. This is a large, male Pteranodon skull. The was the same AMNH expedition that included the discovery of the

"Fish-within-a-fish" specimen by Sorenson.

The specimen is currently on exhibit at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Photo provided to G.F. Sternberg by Bob Schaeffer in January, 1953. |

|

LEFT: A recent (2008) photo by Vincent Smith of AMNH FR75165, including the reconstruction of a male crest. Copyright ©2008 by Vincent Smith. Used with permission. |

|

LEFT: The nearly complete skull of an adult Pteranodon

sternbergi female (KUVP 2212;

Williston, 1892, Pl. I; see also Bennett,

1992, fig. 3), from Trego County, Kansas. The specimen was collected by

E.C.

Case in 1892, and prepared by H.T. Martin. The skull is 78 cm long. The missing portion of

the lower jaw is colored dark gray. At the time of its discovery, it was the best skull

known.

RIGHT: A portion of the composite Pteranodon specimen on exhibit in the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History. |

|

|

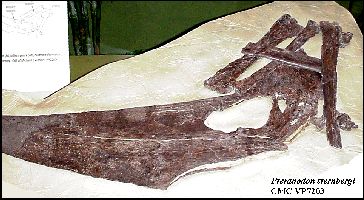

LEFT: The nearly complete skull and lower

jaws of a sub-adult male Pteranodon sternbergi (CMC VP 7203) found by my wife,

Pam, in 1996 and later donated to the Cincinnati Museum Center. Note that the end of

the beak was missing when collected, and that the bones around the crest are from one of

the wings that was wrapped around the skull as prior to burial. The radius and ulna are in

front of the skull. The other two bones are probably metacarpal IV and the 1st wing

phalanx. Two small finger bones are lying across the frontal. Note that the crest is still

relatively small on this young male. Based on the size of the wing bones, I estimated that

this individual would have had wing spread of about 5.6 m ( 18 ft). I believe that

this is probably one of the 10 best Pteranodon skulls ever collected from the

Smoky Hill Chalk.

RIGHT: Close up of CMC VP 7203 in left lateral view. showing the large naral fenestra and orbit of the left eye. One or more cervical vertebrae are still articulated with the occipital condyle. Both lower jaws are present and still articulated with the skull. No post-cranial material below the shoulders was collected. |

|

Nyctosaurus gracilis and N. nanus Marsh

Nyctosaurus (Night Lizard) was a smaller pterosaur that presently occurs only (see note below) in the Smoky Hill Chalk of western Kansas. According the Bennett (1994), there are two valid species; Nyctosaurus nanus in the lower Smoky Hill Chalk and N. gracilis in the upper chalk. N. gracilis was described by O. C. Marsh in 1876 and N. nanus (YPM 1182) was described by Marsh in 1881. Marsh did not figure the specimens but they were shown as photographs by Schoch (1984). Other than size, the skeleton of Nyctosaurusdiffered from P. longiceps most noticeably in the shape of the humerus (upper wing bone), and in the lack of a crest on the skull (Note: see crested Nyctosaurusspecimen below).

Here is the original description of Nyctosaurus gracilis by Marsh (1876): "A second genus of American Pterodactyls is represented in the Yale Museum by several well preserved specimens. This genus is nearly related to Pteranodon, but may be readily distinguished from it by the scapular arch, in which the coracoid is not coossified with the scapula. The latter bone, moreover, has no articulation at its distal end, which is comparatively thin and expanded. The type of this genus is Pteranodon gracilis Marsh, which may now be called Nyctosaurus gracilis. It was a Pterodactyl of medium size, measuring about eight to ten feet between the tips of the expanded wings. Its locality is in the upper Cretaceous of Western Kansas. The type specimens of all the above species are preserved in the Museum of Yale Col1ege."

At the 2000 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology annual meeting in

Mexico City, Chris Bennett mentioned a very large Nyctosaurus specimen:

"A third new specimen from higher in the

Smoky Hill Chalk Member, although incomplete, is the largest known specimen of Nyctosaurus,with an estimated wingspan of 4.5 m. Thus known specimens of

Bennett, S. C. 2000. New information on the skeletons of Nyctosaurus. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 20(Supplement to Number 3): 29A. (Abstract)

Note that a new species of nyctosaur (Muzquizopteryx coahuilensis n.gen., n.sp.)was reported from the Austin Chalk of northern Mexico by Stinnesbeck et al. (2005)

|

LEFT: The right shoulder of FHSM VP-405 as shown on exhibit.

Right: The left humerus of FHSM VP-405. Note the distinctive "hatchet" shape of the humerus in Nyctosaurus. |

|

|

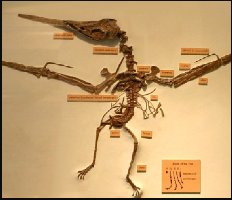

LEFT: The type specimen of Nyctosaurus bonneri (FHSM VP-2148) at the Sternberg Museum, collected from

southeastern Logan County in 1962 by G.F. Sternberg. Bennett (1994) considered N.

bonneri to be a junior synonym of N. gracilis.

Nyctosaurus had 9 cervicals, 12 dorsals, 6 sacrals and at least 3 caudal vertebrae (Bennett 2001). RIGHT: A slightly different view of FHSM VP-2148 showing the distal wing phalanges I, II and III of another Nyctosaurus specimen (FHSM VP-405). Nyctosaurus had one less digit (3) in its wing than did Pteranodon (4). |

|

|

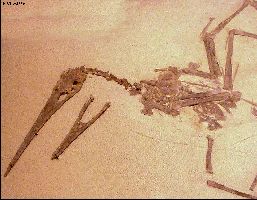

LEFT and RIGHT: The first nearly complete specimen of Nyctosaurus gracilis at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, IL. P 25026 was described by Williston (1902). Collected by H. T. Martin in Gove County, Kansas about 1901. (Photographed in 2003) |  |

|

LEFT: The skull and lower jaw of Nyctosaurus gracilis (P

25026). This was one of the first pteranodon skulls ever to be photographed for

publication (Williston, 1902).

RIGHT: The post-cranial skeleton of P 25026. Click here for a photograph of the lower body of this specimen by Williston (1903, Plate 40) |

|

|

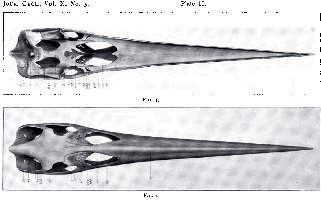

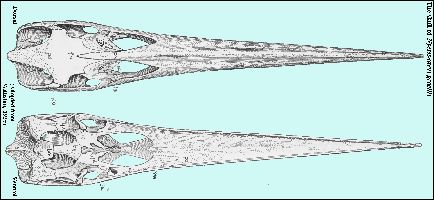

LEFT: Skull of P 25026 in ventral and dorsal views,

adapted from Williston (1902, plate II).

RIGHT: Palate of Nyctosaurus gracilis, P25026, adapted from

Williston (1902, Plate I): Under

surface of the posterior part of skull, lying in matrix slightly enlarged.

Near the anterior end are seen the two hyoid bones, and in the occipital

region, the small triangular pro-atlas. |

|

|

LEFT: Dorsal and ventral views of the skull of Nyctosaurus

gracilis Marsh. Adapted from Williston (1925, Pl. 72).

RIGHT: Dorsal view of a nearly complete specimen of a Nyctosaurus gracilis (UNSM 93000) from the Smoky Hill Chalk of Logan County in western Kansas and currently on exhibit in the University of Nebraska State Museum, Lincoln Nebraska. Collected near Elkader, Kansas and prepared by Greg Brown (Brown, 1978, 1986), this specimen is significant because it shows that Nyctosaurus had three wing phalanges, not four as shown by Williston (above). The wingspread on this specimen would have been about 2.4 m (8 ft). Note that what appears to be a wing claw on the left wing is actually a bone fragment from phalanx I. |

|

|

LEFT: A mostly articulated Nyctosaurus specimen (AMNH FR

1716)

collected by H.T. Martin in 1920 from Logan County, Kansas and sold to the

Carnegie Museum in Pittsburg, PA. It was then traded to the AMNH in

1941.

RIGHT: A cast of the same Nyctosaurus specimen reconstructed about 1941 for exhibit in the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH FR 1716). Note that the wings and lower legs are all reconstructed. In this case the wings are wrong because they include the 4 phalange and wing claws. The same specimen is shown in a 1943 article entitled "Flying Reptiles" by Barnum Brown. |

|

The recent discovery in the Smoky Hill Chalk of western Kansas of two specimens of Nyctosaurus with very large crests is discussed in a paper by Chris Bennett: Bennett, S. C. 2003. New crested specimens of the Late Cretaceous pterosaur Nyctosaurus. Paleontologist Zeitschrift, 77:61-75. (See photographs of the actual specimens here:Chris Bennett web page). Note that these specimens are small (2 m wingspread) and were collected in the lower chalk of Trego County. Based only on their stratigraphic occurrence, it is likely they represent mature males of the earlier smaller species, Nyctosaurus nanus (Marsh, 1881)

|

LEFT: The most recently collected partial specimen of Nyctosaurus... probably Nyctosaurus nanus since it was collected in the lower Smoky Hill Chalk of western Gove County, Kansas. Specimen is in a private collection; photos used with permission. |

|

LEFT: A closer view of the head of the same specimen, showing an unusual dorsal view of the top of the skull (frontals) and the prefrontals. Note that this specimen shows no evidence of a crest of any sort. (Frontal in dorsal view here). The lower jaw is complete except for a small portion of the distal end. All of the cervical vertebrae are present (four are shown here) |

Pteranodons from the Pierre Shale - The last pteranodons

While most Pteranodon specimens have been collected from the Smoky Hill Chalk Member (Late Coniacian - Early Campanian) in Kansas, there are a significant number specimens (60+) known from the Pierre Shale Group in South Dakota, Wyoming and Kansas (Early to Middle Campanian), including one specimen supposedly collected by Barnum Brown (1904) as stomach contents of a plesiosaur (See Hargrave, 2007, for discussion of Pierre Shale specimens in the Geology Museum at the South Dakota School of Mines). From the specimens that have been found to date, it appears that pteranodons flourished in North America from from about 90 mya to about 80 mya. They may have been around a lot longer but their remains are fragile and not easily preserved in most environmental settings. The Smoky Hill Chalk, deposited far from shore, apparently had the best conditions for the preservation of large numbers of these flying reptiles.

|

LEFT: KUVP 27821 - A partial Pteranodon sp. skull in right lateral view from the Sharon Springs Fm. (formerly the Sharon Springs Member of the Pierre Shale), Edgemont area, southwestern South Dakota (figured by Bennett, 1992, Fig. 4E; Carpenter. 2006, Fig. 14 B). A photo of a Pteranodon bone (KUVP 33564) from the Pierre Shale of western Kansas is shown here Note that Kellner (2010) described this specimen as the holotype of a new species - "Geosternbergia maiseyi” sp. nov. |

The following chart provides some information regarding where the specimens were collected and in what museum they are curated:

|

Pierre Shale Pteranodon specimens- (Updated from Carpenter dissertation (1996) Number Locality Material Comments AMNH 5803 Loc.

4

plesiosaur Pteranodon bones as stomach contents in concretion in a plesiosaur (AMNH FR 5803) See Brown, 1904 |

Earliest (oldest) pterosaur specimens from Kansas

Chris Bennett's Pterosaur webpage HERE

See The Pterosaur Database HERE

Pterosaur Site (Jurassic pterosaurs) HERE

Further reading:

Anonymous. 1872. On two new Ornithosaurians from Kansas. American Journal of Science, Series 3, 3(17):374-375. (Probably written by O. C. Marsh)

Arbour,

V. M. and Currie, P.J.(2011. An istiodactylid pterosaur from the Upper

Cretaceous Nanaimo Group, Hornby Island,

Arbour, V.M. and Currie, P.J. 2011. Corrigendum: an istiodactylid pterosaur from the Upper Cretaceous Nanaimo Group, Hornby Island, British Columbia, Canada. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 48:778.

Bennett, S. C. 1987. New evidence on the tail of the pterosaur Pteranodon(Archosauria: Pterosauria). pp. 18-23 In Currie, P. J. and E. H. Koster (eds.), Fourth Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems, Short Papers. Occasional Papers of the Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology, #3.

Bennett, S.C. 1990. Inferring stratigraphic position of fossil vertebrates from the Niobrara Chalk of western Kansas. pp. 43-72, In Bennett, S. C. (ed.), Niobrara Chalk Excursion Guidebook, The University of Kansas Museum of Natural History and the Kansas Geological Survey.

Bennett, S.C. 1992. Sexual dimorphism of Pteranodon and other pterosaurs, with comments on cranial crests. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 12 p. 422-434.

Bennett, S.C.1993. The ontogeny of Pteranodon and other pterosaurs. Paleobiology 19(1):92-106.

Bennett, S.C. 1994. Taxonomy and systematics of the Late Cretaceous pterosaur Pteranodon (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea). Occasional Papers of the Natural History Museum, University of Kansas. 169:1-70.

Bennett ,

Bennett ,

Bennett, S.C. 2000. Inferring Stratigraphic Position of Fossil Vertebrates from the Niobrara Chalk of western Kansas. KansasGeological Survey, Current Research in Earth Sciences, Bulletin 244, part 1. Photos are here

Bennett, S.C. 2000. Pterosaur flight: the role of actinofibrils in wing function. Historical Biology, 14:255-284.

Bennett, S.C. 2000. New information on the skeletons of Nyctosaurus. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 20(Supplement to Number 3): 29A. (Abstract)

Bennett, S.C. 2001. The osteology and functional morphology of the Late Cretaceous pterosaur Pteranodon. Part I. General description of osteology. Palaeontographica, Abteilung A, 260:1-112.

Bennett, S.C. 2001.The osteology and functional morphology of the Late Cretaceous pterosaur Pteranodon. Part II. Functional morphology. Palaeontographica, Abteilung A, 260:113-153.

Bennett, S.C. 2003. New crested specimens of the Late Cretaceous pterosaur Nyctosaurus. Paläontologische Zeitschrift, 77:61-75.

Bennett, S.C. 2003. A survey of pathologies of large pterodactyloid pterosaurs. Palaeontology 46(1):185-198.

Bennett, S.C. 2007. Articulation and function of the pteroid bone of pterosaurs. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27:881-891.

Betts, C. W. 1871. The Yale College expedition of 1870. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, 43(257):663-671. (Issue of October, 1871)

Bonner, O. W. 1964. An osteological study of Nyctosaurusand Trinacromerum with a description of a new species of Nyctosaurus.Unpub. Masters Thesis, Fort Hays State University, 63 pages.

Brower, J. C. 1983. The aerodynamics of Pteranodonand Nyctosaurus, two large pterosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous of Kansas. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 3(2):84-124.

Brower, J.C. 1983. The aerodynamics of Pteranodonand Nyctosaurus, two large pterosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous of Kansas. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 3(2):84-124.

Brown, B.1904. Stomach stones and the food of plesiosaurs. Science, 20(501):184-185.

Brown, B. 1943. Flying reptiles. Natural History. 52:104-111.

Brown, G.W. 1978. Preliminary report on an articulated specimen of Pteranodon (Nyctosaurus) gracilis (abstr.). Nebraska Academy of Sciences, Proceedings 88:39.

Brown, G.W. 1986. Reassessment of Nyctosaurus; new wings for an old pterosaur (abstr.). Nebraska Academy of Sciences, Proceedings 96:47.

Brown, G. 1986. Evidence of phalangeal reduction in the wing of the pterosaur Nyctosaurus. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, Abstracts of the Annual Meeting.

Carpenter, K. 1996. Sharon Springs Member, Pierre Shale (Lower Campanian) depositional environment and origin of its vertebrate fauna, with a review of North American plesiosaurs. Unpub. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Colorado, 251 pp.

Carpenter, K. 2006. Comparative vertebrate taphonomy of the Pembina and Sharon Springs members (Middle Campanian) of the Pierre Shale, Western Interior. Paludicola 5:125-149.

Claessens, L. P. A. M., O’Connor, P.M., and Unwin, D. M. 2009. Respiratory evolution facilitated the origin of pterosaur flight and aerial gigantism. PLoS ONE 4(2): 1-8. (AVAILABLE ONLINE)

Cope,

E.D. 1866. Communication in regard to the Mesozoic sandstone of

Cope,

E.D. 1870. Rhabopelix longispinis,

Cope., pp. 169-175 in Synopsis of

the extinct Batrachia, Reptilia and Aves of

Cope, E. D. 1872. On the geology and paleontology of the Cretaceous strata of Kansas. Annual Report of the U. S. Geological Survey of the Territories 5:318-349 (Report for 1871).

Cope, E. D. 1872. On two new ornithosaurians from Kansas. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 12(88):420-422.

Cope, E. D. 1874. Review of the vertebrata of the Cretaceous period found west of the Mississippi River. U. S. Geological Survey of the Territories Bulletin 1(2):3-48.

Cope, E. D. 1875. The vertebrata of the Cretaceous formations of the West. Report, U. S. Geological Survey of the Territories (Hayden). 2:302 p, 57 pls.

Currie, P.J., and Padian, K. 1983. A new pterosaur record from the Judith River (Oldman) Formation of Alberta. Journal of Paleontology 57(3):599-600.

Currie, P.J. and Russell D.A. 1982. A giant pterosaur (Reptilia: Archosauria) from the Judith River Oldman Formation of Alberta. Canadian Journal of Earth Science. 19: 894-897.

Eaton, G. F. 1903. The characters of Pteranodon. American Journal of Science, ser. 4, 16(91):82-86, pl. 6-7.

Eaton, G. F. 1904. The characters of Pteranodon(second paper). American Journal of Science, ser. 4, 17(100):318-320, pl. 19-20.

Eaton, G. F. 1908. The skull of Pteranodon. Science (n. s.) XXVII 254-255.

Eaton, G. F. 1910. Osteology of Pteranodon. Memoirs of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2:1-38, pls. i-xxxi.

Edinger, T. 1927. Das Gehirn der Pterosaurier. Zeitschrift Anat. Entwicklungsgeschichte 83:105-112. ["The brain of the pterosaur" - In German]

Elgin, R.A., Grau, C.A., Palmer, C., Hone, D.W.E., Greenwell, D. and Benton, M.J. 2008. Aerodynamic characters of the cranial crest in Pteranodon. Zitteliana B28:167-174.

Elgin, R.A., Hone, D.W.E., and Frey, E. 2011. The extent of the pterosaur flight membrane. Acta Palaeontologica. Polonica 56(1):99-111.

Everhart, M. J. and Everhart, P. 1999. An early occurrence of Pteranodon sternbergi from the Smoky Hill Member (Late Cretaceous) of the Niobrara Chalk in western Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science, Abstracts of the 131st Annual Meeting 18:27.

Frey, E., Buchy, M.-C. Martill and D.M. 2003. Middle- and bottom-decker Cretaceous pterorsaurs: unique designs in active flying vertebrates. in Buffetaut, E. and Mazin, J.-M. (eds.), Evolution and Paleobiology of Pterosaurs. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 217:267-274.

Frey, E. Martill, D.M. and Buchy, M.-C. 2003. A new species of tapejarid pterosaur with soft-tissue head crest. in Buffetaut, E. and Mazin, J.-M. (eds.), Evolution and Paleobiology of Pterosaurs. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 217:65-72.

Frey, E., Buchy, M.-C., Stinnesbeck,

W., González- González, A. and Stefano, A. 2006. Muzquizopteryx

coahuilensis n.g., n.sp., a nyctosaurid pterosaur with soft tissue

preservation from the Coniacian (Late Cretaceous) of northeast

Habib, M. 2008. Comparative

evidence for quadrupedal launch in pterosaurs. Pp 159-166 in Buffetaut E., and

D.W.E. Hone (eds.), Wellnhofer Pterosaur Meeting: Zitteliana B28.

Hargrave, J.E. 2007. Pteranodon (Reptilia: Pterosauria): Stratigraphic distribution and taphonomy in the lower Pierre Shale Group (Campanian), western South Dakota and eastern Wyoming. p.215-225 in Martin, J.E. and Parris, D.C. (eds.), The Geology and Paleontology of the Late Cretaceous Marine Deposits of the Dakotas. Geological Society of America, Special Paper 427.

Harksen, J. C. 1966. Pteranodon sternbergi, a new fossil pterodactyl from the Niobrara Cretaceous of Kansas. Proceedings South Dakota Academy of Science 45:74-77.

Henderson, M.D. and Peterson, J.E. 2006. An Azhdarchid pterosaur cervical vertebra from the Hell Creek Formation (Maastrichtian) of southeastern Montana. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 26(1):192–195.

Henderson, D.M. 2010. Pterosaur body mass estimates from three-dimensional mathematical slicing. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30(3):768-785.

Huene,

F. von. 1921. Reptilian and stegocephalian remains from the Triassic of

Humphries, S., Bonser, R.H.C., Witton, M.P., and Martill, D.M. 2007. Did pterosaurs feed by skimming? Physical modeling and anatomical evaluation of an unusual feeding method. PLoS Biology 5(8):1648-1655.

Kellner,

A.W.A. 2010. Comments on the Pteranodontidae (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea)

with description of two new species. Anais da Academa Brasileira de Ciências

82(4):1063-1084.

Lane, H. H. 1946. A survey of the fossil vertebrates of Kansas, Part III, The Reptiles, Kansas Academy Science, Transactions 49(3):289-332, figs. 1-7.

Liggett, G. A., S. C. Bennett, K. Shimada and J. Huenergarde. 1997. A Late Cretaceous (Cenomanian) fauna in Russell county, KS. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions Abstracts. 16:26

Liggett, G. A., K. Shimada, S. C. Bennett and B. Schumacher. 2005. Cenomanian (Late Cretaceous) reptiles from northwestern Russell County, Kansas. PaleoBios 25(2): 9-17.

Lü, J., Unwin, D.M., Deeming, D.C., Jin, X., Liu, Y. and Ji, Q. 2011. An egg-adult association, gender, and reproduction in pterosaurs. Science 331(6015):321-324. (January 21, 2011)

Lucas,

F.A. 1902. The greatest flying creature, the great Pterodactyl Ornithostoma.

Report of the Smithsonian Institution 1901:654-659.

Marsh, O. C. 1871. Scientific expedition to the Rocky Mountains. American Journal of Science ser. 3, 1(6):142-143.

Marsh, O. C. 1871. Notice of some new fossil reptiles from the Cretaceous and Tertiary formations. American Journal of Science, Series 3, 1(6):447-459.

Marsh, O. C. 1871. Note on a new and gigantic species of Pterodactyle. American Journal of Science, Series 3, 1(6):472.

Marsh, O. C. 1872. Discovery of additional remains of Pterosauria, with descriptions of two new species. American Journal of Science, Series 3, 3(16) :241-248.

Marsh, O. C. 1876. Notice of a new sub-order of Pterosauria. American Journal of Science, Series 3, 11(65):507-509.

Marsh, O. C. 1876. Principal characters of American pterodactyls. American Journal of Science, Series 3, 12(72):479-480.

Marsh, O. C. 1881. Note on American pterodactyls. American Journal of Science, Series 3, 21(124):342-343.

Marsh, O. C.. 1882. The wings of Pterodactyles. American Journal of Science, Series 3, 23(136):251-256, pl. III.

Marsh, O. C. 1884. Principal characters of American Cretaceous pterodactyls.

Part I. The skull of Pteranodon. American Journal of Science, Series 3,

27(161):422-426, pl. 15.

Mateer, N.J. 1975. A study of Pteranodon. Bulletin of the Geological Institutions of Uppsala 6:23-33.

Matthew, W.D. 1916. A reptilian aëronaut; a new

skeleton of the giant flying reptile of the Cretaceous Period.

Matthew, W.D. 1920. Flying Reptiles. Natural History 20:73-81.

Miller, H. W. 1971. The taxonomy of the Pteranodonspecies from Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 74(1):1-19.

Miller, H. W. 1971. A skull of Pteranodon (Longicepia)longiceps Marsh associated with wing and body parts. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 74(10):20-33.

Miller, H.W. 1978. Geosternbergia, a new name for SternbergiaMiller, 1972: Non Paulo Couto 1970; non Jordon, 1925. Journal of Paleontology 52(1):194.

Myers,

T.S. 2010. Earliest occurrence of the Pteranodontidae (Archosauria: Pterosauria)

in North America: New material from the Austin Group of Texas. Journal of Paleontology 84(6):1071-1081.

Myers, T.S. 2010. A new ornithocherid pterosaur from the Upper Cretaceous (Cenomanian-Turonian) Eagle Ford Group of Texas. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30(1):280–287.

Padian, K. 1983. A functional analysis of flying and walking in pterosaurs. Paleobiology 9(3):218-239.

Padian, K. 1984. A large pterodactyloid pterosaur from the Two Medicine Formation (Campanian) of Montana. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 4(4):516-524.

Padian, K., and Smith, M. 1992. New light on Late Cretaceous pterosaur material from Montana. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 12(1): 87-92.

Russell, D.A. 1988. A check list of North American marine cretaceous vertebrates including fresh water fishes, Occasional Paper of the Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology, (4):57.

Schoch, R.M. 1984. Notes on the type specimens of Pteranodon and Nyctosaurus (Pterosauria, Pteranodontidae) in the Yale Peabody Museum Collections. Postilla 194:1-23.

Schultze, H.-P., L. Hunt, J. Chorn and A. M. Neuner. 1985. Type and figured specimens of fossil vertebrates in the collection of the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History, Part II. Fossil Amphibians and Reptiles. Miscellaneous Publications of the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History 77:66 pp.

Schwimmer, D. R. Padian, K., and Woodhead, A.B. 1985. First pterosaur records from Georgia: Open marine facies, Eutaw Formation (Santonian). Journal of Paleontology 59(3):674-676.

Seeley, H. G. 1870. The Ornithosauria: an elementary study of the bones of pterodactyles. Deighton, Bell, and Co., Cambridge, xviii + 135 pp.

Seeley, Harry G. 1871. Additional evidence of the structure of the head in ornithosaurs from the Cambridge Upper Greensand; being a supplement to "The Ornithosauria." The Annals and Magazine of Natural History, Series 4, 7:20-36, pls. 2-3. (Discovery of toothless pterosaurs in England)

Shor, E. N. 1971. Fossils and flies; The life of a compleat scientist - Samuel Wendell Williston, 1851-1918, University of Oklahoma Press, 285 pp.

Sneyd, A.D., Bundock, M.S. and Reid. D. 1982. Possible effects of wing flexibility on the aerodynamics of Pteranodon. The American Naturalist 120(4):455-477.

Stein, R.S. 1975. Dynamic analysis of Pteranodon ingens: A reptilian adaptation to flight. Journal of Paleontology 49(3):534-548.

Sternberg, C. H. 1990. The life of a fossil hunter, Indiana University Press, 286 pp. (Originally published in 1909 by Henry Holt and Company)

Sternberg, G.F. and M.V. Walker. 1958. Observation of articulated limb bones of a recently discovered Pteranodon in the Niobrara Cretaceous of Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions, 61(1):81-85.

Stewart, J. D. 1990. Niobrara Formation vertebrate stratigraphy. pp. 19-30 in Bennett, S. C. (ed.), Niobrara Chalk Excursion Guidebook, The University of Kansas Museum of Natural History and the Kansas Geological Survey.

Stinnesbeck, W., Ifrim, C., Schmidt, H.,

Rindfleisch, A., Buchy, M.-C., Frey, E., González-González, A.H., Vega, F.J.

Cavin, L., Keller, G. and Smith, K.T. 2005. A new lithographic limestone deposit

in the Upper Cretaceous Austin Group at El Rosario,

Vullo, R., Buffetaut, E. and Everhart, M.J. 2012. Reappraisal of Gwawinapterus beardi from the Late Cretaceous of Canada: A saurodontid fish, not a pterosaur. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 32(5):1198-1201.

Wang, X. and Z. Zhou. 2004. Pterosaur embryo from the Early Cretaceous. Nature 429:621.

Webb, W. E. 1872. Buffalo Land - An authentic account of the discoveries, adventures, and mishaps of a scientific and sporting party in the Wild West. Hubbard Bros., Philadelphia, 503 pp.

Wellnhoffer, P. 1978. Pterosauria. Handbuch der Paläeoherpetologie, Tiel 19, x+82 pp. Gustav Fisher Verlag, Stuttgart.

Wellnhofer, P. 1991. The illustrated encyclopedia of pterosaurs. Crescent Books, New York, 192 pp.

Williston,

S.W. 1885. Über Ornithocheirus hilsensisKoken. Zoologische Anzeiger 8:628-629.

Williston, S.W. 1891. The skull and hind extremity of Pteranodon. American Naturalist 25(300):1124-1126.

Williston, S.W. 1892. Kansas pterodactyls. Part I. Kansas University Quarterly 1:1-13, pl. i.

Williston, S.W. 1893. Kansas pterodactyls. Part II. Kansas University Quarterly 2:79-81, with 1 fig.

Williston, S.W. 1895. Note on the mandible of Ornithostoma. Kansas University Quarterly 4:61.

Williston, S.W. 1896. On the skull of Ornithostoma. Kansas University Quarterly 4(4):195-197, with pl. i.

Williston, S.W. 1897. Restoration of Ornithostoma (Pteranodon). Kansas University Quarterly 6:35-51, with pl. ii.

Williston, S.W. 1902. On the skeleton of Nyctodactylus, with restoration. American Journal of Anatomy. 1:297-305.

Williston, S.W. 1902. On the skull of Nyctodactylus, an Upper Cretaceous pterodactyl. Journal of Geology, 10:520-531, 2 pls.

Williston, S.W. 1902. Winged reptiles. Pop. Science Monthly 60:314-322, 2 figs.

Williston, S.W. 1902. Review of Seeley's Dragons of the Air. Science 15(367):67-68.

Williston, S.W. 1903. On the osteology of Nyctosaurus (Nyctodactylus), with notes on American pterosaurs. Field Mus. Publ. (Geological Ser.) 2(3):125-163, 2 figs., pls. XL-XLIV.

Williston, S.W. 1904. The fingers of pterodactyls. Geology Magazine, Series 5, 1(2): 5:59-60.

Williston, S.W. 1910. A mounted skeleton of Platecarpus. Journal of Geology 18(6):537-541, 1 fig. (Notes that he has seen evidence of a fibula in Pteranodon)

Williston, S.W. 1911 The wing-finger of pterodactyls, with restoration of Nyctosaurus. Journal of Geology. 19:696–705.

Williston, S.W. 1912. A review of G. F. Eaton's "Osteology of Pteranodon." Journal of Geology. 20:288.

Wiman, C. 1920. Some reptiles from the Niobrara Group in Kansas. Bulletin of the Geological Institution of the University of Upsala, Upsala, 18:9-18.

Witton,

M.P. 2010. Pteranodon and beyond: the

history of giant pterosaurs from 1870 onwards. pp. 313-323 in Moody, R.T.J.,

Buffetaut, E., Naish, D. and Martill, D.M. (eds.), Dinosaurs and Other Extinct Saurians: A Historical Perspective.

Geological Society,

Witton,

M.P. and Habib, M.B. 2010. On the size and flight diversity of giant pterosaurs,

the use of birds as pterosaur analogues and comments on pterosaur flightlessness.

PLoS One 5(11):1-18.

Witton, M.P. and Naish, D. 2008. A reappraisal of Azhdarchid pterosaur functional morphology and paleoecology. PLoS Biology 3(5):1-16.