|

Protostega gigas dig:

October 21 and 23, 2011

Copyright

©2012-2012 by Mike Everhart

Page created 10/24/2011- Last updated

04/18/2016

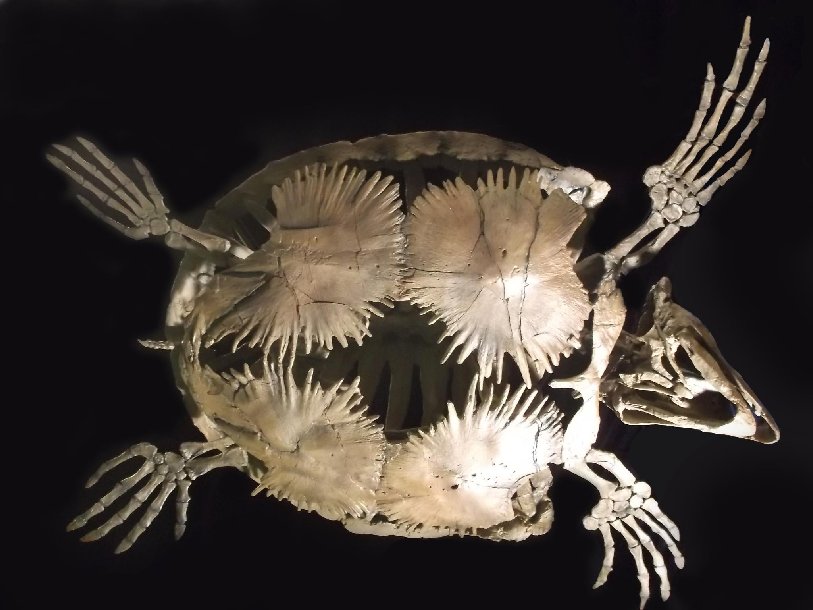

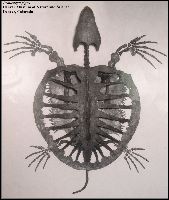

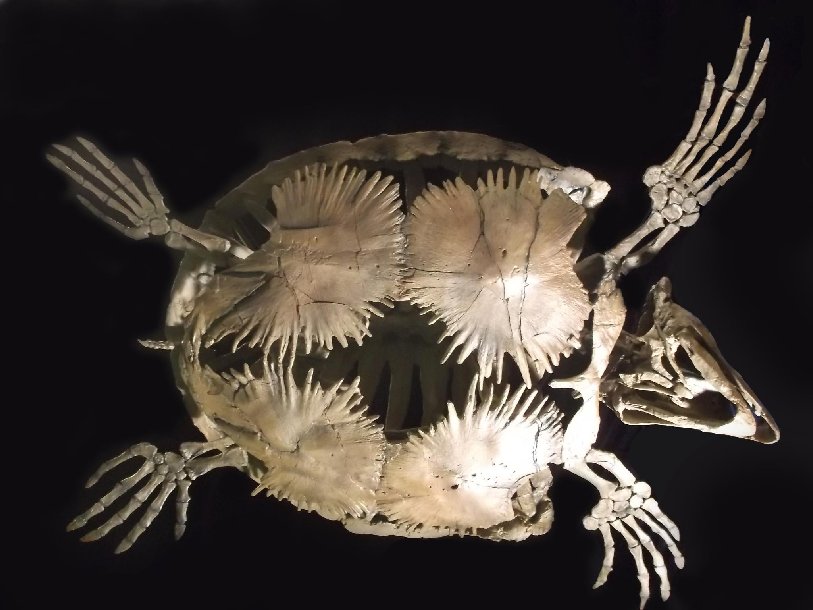

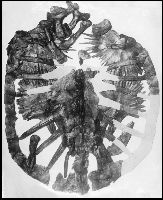

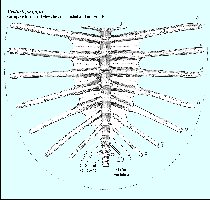

RIGHT: Ventral view of

the cast of the Protostega gigas Cope (FHSM VP-17979) recently

completed by Triebold Paleontology. Photo by Triebold Paleontology ©

2013. |

Protostega gigas Cope was the largest marine turtle in the

Western Interior Sea during the deposition of the Smoky Hill Chalk. The first

fragmentary specimen (YPM 1408) was actually discovered a few miles east of Fort

Wallace by O.C. Marsh and the 1871 Yale Scientific Expedition, but was never

described.

E.D. Cope discovered and collected the type specimen of Protostega gigas (AMNH FR 1503) during his only trip to the Kansas chalk in 1871. He wrote about his

experiences, including the discovery of Protostega, in

a letter dated October 9, 1871 to Professor Lesley of the American

Philosophical Society:

"On another occasion, we detected unusually attenuated

bones projecting from the side of a low bluff of yellow chalk, and some pains

were taken to uncover them. They were found to belong to a singular reptile, of

affinities probably to the Testudinata, this point remaining uncertain. Instead

of being expanded into a carapace, the ribs are slender and flat. The tubercular

portion is expanded into a transverse shield to beyond the capitular

articulation, which thus projects as it were in the midst of a flat plate. These

plates have radiating lines of growth to the circumference, which is dentate.

Above each rib was a large flat ossification of much tenuity, and digitate on

the margins, which appears to represent the dermo-ossification of the Tortoises.

Two of these bones were recovered, each two feet across. The femur resembles in

some measure that ascribed by Leidy to Platecarpus tympaniticus, while

the phalanges are of great size. Those of one series measured eight inches and a

half in length, and are very stout, indicating a length of limb of seven feet at

least. The whole expanse would thus be twenty feet if estimated on a Chelonian

basis. The proper reference of this species cannot now be made, but both it and

the genus are clearly new to science, and its affinities not very near to those

known. Not the least of its peculiarities is the great tenuity of all the bones.

It may be called Protostega gigas."

E. D. Cope, 1871

|

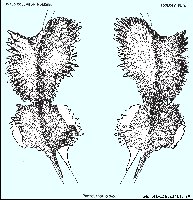

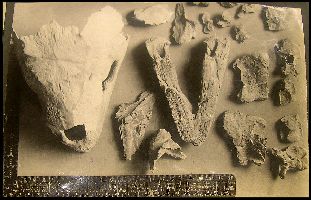

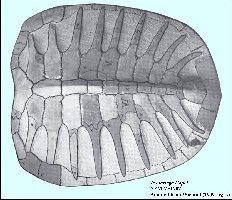

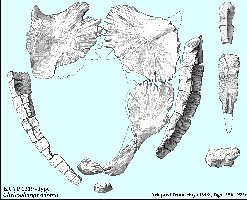

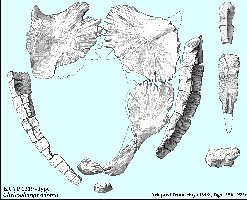

LEFT: The left plastron from the type specimen of Protostega

gigas Cope 1872 as published on Plate IV by Hay, 1895. It measures 1.2

m (almost 4 ft) from left to right and came from a turtle that measured

about 3.0 m (10 ft) long (from nose the end of the tail). The specimen is

curated in the American

Museum of Natural History as FR 1503. (Anterior to the left). "This plate represents the hyoplastron and hypoplastron of the

left side of Protostega gigas seen from below. A view is also given

of the nuchal bone." (Hay, 1895).

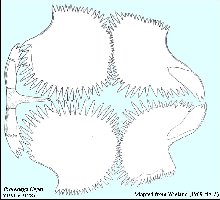

RIGHT: Plate V from Hay 1895: “A

partial restoration of the plastron of Protostega,

to show the relative positions of the bones and the size of the fontanelle.

Only the bases of the epiplastra and of the xiphiplastra are shown.” |

|

Since the initial discovery by Cope, a number of fairly completeProtostega specimens have been collected from Kansas, mostly by Charles

Sternberg and his son, George F. Sternberg. The incomplete specimen (above)

currently on exhibit at the Sternberg Museum of Natural History in Hays was

collected by George F. Sternberg from Gove County in April, 1930. The specimen

is missing the skull and most of the limbs. It's carapace is about 42 inches in

diameter, a bit larger than the new specimen. More

about Cretaceous turtles in Kansas here.

Paddle bones and other elements of the new fossil turtle were

discovered eroding out of the Smoky Hill Chalk during the summer of 2011 in

eastern Gove County by Susan Liebl. Initially the bones were considered to be

part of a mosasaur, but when elements of a carapace were also recovered, it

became apparent that it was part of a marine turtle that once swam in the

Western Interior Sea more than 85 million years ago. Susan contacted me and we

made plans to visit the site on September 29, 2011. At this point, it was

unclear what kind of turtle was there. The age of the specimen is early Middle

Santonian (about 86 million years ago). This is the same

canyon where I collected the earliest known Tylosaurus proriger (FFHM

1997-10) in 1995-96.

Citation: Everhart, M.J. 2013. A new specimen

of the marine turtle, Protostega gigasCope (Cryptodira; Protostegidae), from the Late Cretaceous Smoky Hill Chalk of

Western Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 116(1-2):73.

|

LEFT: On September 29, Susan and I

returned to the site and uncovered some additional bones, including what

appeared to be a complete rear paddle of the turtle. It became

quickly apparent that these bones represented the tail end of a fairly

large turtle and I decided that we did not have the right resources to dig

further.

RIGHT: On the second day of our dig (October 20), we began

uncovering more of the turtle and discovered that the rear limbs appeared

to be complete and articulated. The right rear paddle was in place and

Susan had collected most of the left rear paddle as float during her

initial visit to the site. Much of the chalk containing the ribs of the

carapace was already fragmented due to weathering. We marked and

removed some of the ribs and discovered the bones of the pelvis. We

eventually removed the right rear paddle and the left tibia and fibula to

keep them from being damaged. |

|

|

LEFT: In this photo, the left femur is

visible (still in articulation with the pelvis), as is the right tibia and

fibula. The bones of the pelvis are beginning to emerge from the

surrounding chalk just above the ruler. As we moved deeper into the slope,

we had to remove the left femur and the right tibia/fibula. In the

process, the right femur was located, still articulated with the pelvis.

It was also removed. It appears that the turtle is preserved upright. All

the bones appear to be in excellent condition.

RIGHT: As the dig expanded we also located both edges of the shell

(carapace) and discovered that the shell was 80 cm (31 inches) wide,

probably much too large to be Toxochelys latiremis, the most common

turtle in the Smoky Hill Chalk. We also located what appeared to be

elements of the skull at the deepest point in the dig... but as shows very

well in the photograph, the sun was getting low in the western sky and the

shadows made it difficult to continue. By then we also realized that

the project was much larger than the two of us could handle. |

|

|

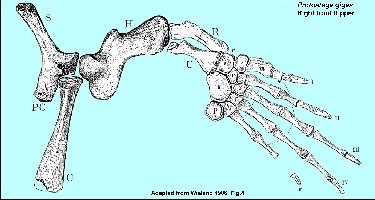

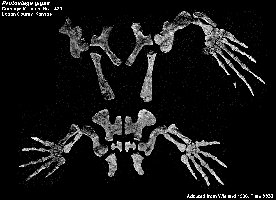

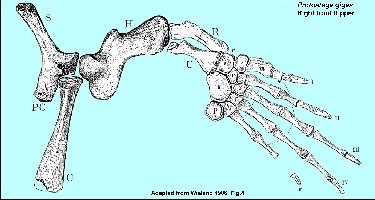

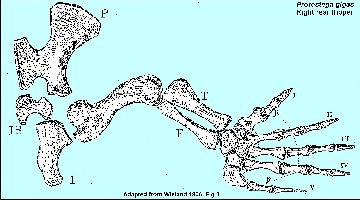

LEFT: Adapted from Wieland 1906, Figure 4. Protostega gigas. Right shoulder girdle and flipper in dorsal view

(CMNH 1421):

S. scapular; PC, procoraco-scapular; C. coronoid; H. humerus; R. radius;

U. ulna; r. radiale; i. intermedium; u. ulnare; c. centrale; 1-5 first to

fifth carpalia; p. pisiform; m. metacarpal 1; p. phalanx 1; I.-V. first to

fifth fingers and ungual phalanges.

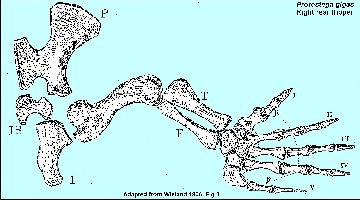

RIGHT: Adapted from Wieland 1906, Figure 5. Protostega

gigas. Right pelvic girdle and flipper in dorsal view: P. pubis; F.

fibula; t. tibiale intermedium and centrale fused, or calcano-astralar

element; 1-3, first to third tarsalia; 4, fourth and fifth tarsalia fused;

m metatarsal 1; p phalanx 1; I.V., first to fifth toes and ungual

phalanges. |

|

|

Fortunately, Mike Triebold and his crew were

also in Kansas collecting fossils. I contacted him and he agreed to come

over on October 22 to assist us in recovering the turtle.

LEFT: On Saturday morning, we met in Quinter and drove out to the

locality where the turtle had been discovered. The first order of the day

was to remove the debris that Susan and I had put on top of the turtle

remains two days earlier to protect them. Photo by Susan Liebl.

RIGHT: We had used plastic to cover the specimen previously. Photo

by Susan Liebl. |

|

|

LEFT: Mike Triebold (center), Anthony Maltese

and Jacob Jett begin enlarging the dig site, using an electric jack

hammer. The gray chalk at this stratigraphic level is dense and

doesn't split cleanly, but the jack hammer made relatively short work of

it. The specimen is at the center of the photo, covered with black

plastic. Susan is looking through the chalk fragments to make sure

we didn't miss any bone.

RIGHT: Mike, Anthony and Jacob continue to enlarge the excavation to

give us enough space to work around the turtle fossil without damaging

it. |

|

|

LEFT: The excavation is enlarged and cleaned

up so that we can actually start working on further isolating the

specimen. Charlie Sternberg would have

referred to this process as "preparing the floor" and I am sure

he would have appreciated the use of power tools.

RIGHT: A view looking at the turtle site from the northwest. Mike

was able to get his truck right next to the dig site, which was good,

considering all the equipment he was able to bring with him, and the

expected weight of the jacket enclosing the turtle. I was not looking

forward to carrying the thing up the hill to where my van is parked. |

|

|

LEFT: Another view of the beginnings of the

dig from above. Anthony, Mike and Susan are moving debris away from the

fossil while Jacob is breaking up more chalk with the jack hammer.

RIGHT: Once we had the work space cleared, we settled in

around the specimen to clean up the area. Photo by Anthony Maltese. |

|

|

LEFT: Here Susan, Mike T., Mike E. and Jacob

look at the project to start making decisions about how the turtle will

come out.

RIGHT: Once we decided what needed to be done, it was time to locate

the outer edges of the turtle. Here Anthony is taking a close look at the

chalk to see where bone may be exposed. Photo by Susan Liebl. |

|

|

LEFT: There were several small pieces of

bone exposed in the chalk where the head and front limbs should have been

located. As they were found, Anthony coated them with preservative to mark

them, and protect them during the next part of the dig. Photo by Susan

Liebl.

RIGHT: Once the area was cleared around the specimen, a perimeter

was marked with orange spray paint to serve as a guide for the next

step... cutting around the fossil with a chain saw. Note that the chalk

matrix containing the specimen is badly fragmented. Consolidant has been

applied to help hold the chalk together, but mostly we are depending on

the strength of the plaster jacket to secure everything in one block. In

this photo, the pelvis is at the top of the image; the skull, if present,

would be at the bottom. |

|

|

LEFT: In this photo, the size of the

excavation is more apparent. Fortunately there was not a lot of

matrix over the top of the specimen. The turtle's pelvis is toward the

lower right of this photo. The orange debris is a a half inch layer of

volcanic ash (bentonite) that was located about 2 inches below the bones.

We were concerned that this might cause problems when turned the jacket

over.

RIGHT: Here Mike Triebold begins cutting through the chalk around

the specimen. The carbide tipped blade of the saw went through the

chalk without any problems, enabling us to isolate the specimen without

having to use hammers and chisels. |

|

|

LEFT: Once the first cut was completed

around the specimen, Mike made a second cut further way to allow us to

open a trench and get under the specimen to make the plaster jacket. The

blade of the saw is angled under the edge of the block containing the

fossil to provide a lip for anchoring the plaster jacket.

RIGHT: Mike finishes the perimeter cut around fossil as the crew and

one of the landowners watch. The day had started off cloudy and cool but

by noon, the sky was clear. |

|

|

LEFT: Jacob uses an air hammer to chisel way

the chalk between the two saw cuts. Eventually we had two air

hammers going with the rest of us clearing out the broken chalk.

RIGHT: Once the trench was open, the block was prepared for

jacketing. Aluminum foil was placed over areas where bone was exposed to

prevent the plaster from adhering to the bones. Thin-walled steel pipe was

added for reinforcement and also to serve as handles under the jacket once

it is turned over. |

|

|

LEFT: This photo shows the large amount of

undercutting that Mike did with the chainsaw. This undercut allowed us to

securely support the lower portion of the matrix. Note the pre-existing,

large cracks in the block of chalk.

RIGHT: Jacob begins mixing the plaster that

will be used to saturate the strips of burlap used in making the jacket.

The tinfoil is used to keep the plaster from sticking to the exposed bones

of the turtle. The lumps of chalk on the tin foil were there to keep the

wind from blowing them away.

At this point, I put the camera down and helped Anthony jacket the

specimen. Photo by Susan Liebl. |

|

|

LEFT: Here Anthony is getting plastered...

um, applying the plaster bandages to the edges of the block of chalk

containing the turtle bones. Who says you can't have fun while you work?

The disposable gloves are a "why didn't I think of that"

addition to the plastering process. We've always done it bare handed in

the past. Photo by Susan Liebl.

RIGHT: Once the perimeter of the jacket was complete we began

applying layers of plaster and burlap bandages to the exposed upper

surface. Several layers of bandages crossing the block in different

directions are used to make a strong jacket that will support the specimen

when it is turned over. Photo by Susan Liebl. |

|

|

LEFT: Anthony and I finish the jacket by

embedding steel pipe that will be used as handles for carrying the jacket

once it is turned. Photo by Susan Liebl.

RIGHT: The finished product... a solid, reinforced plaster jacket

that will hopefully contain the turtle specimen when we turn it

over. But first we waited about an hour for the plaster to

thoroughly set up. During that time, we also dug deeper on the west side

of the jacket (top of photo) to give us space to drive chisels into the

underlying chalk and break the jacket loose. However, we used

the jack hammer instead to free the specimen before rolling it. |

|

|

LEFT: The moment of truth came and went

uneventfully. The jacket was rolled with no problem. We then removed a two

inch layer of chalk to lighten the jacket before we carried it to the

truck.

RIGHT: Once the jacket had been turned, it was time to load up the

equipment and get ready to leave. The jacket containing the turtle bones

was loaded last.

Thanks to Mike Triebold and his crew for helping on the dig. The use

of power tools in this case saved us at least two days on the dig and

minimized the risk of damaging the specimen. |

|

|

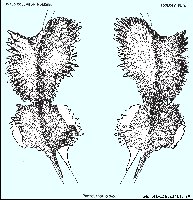

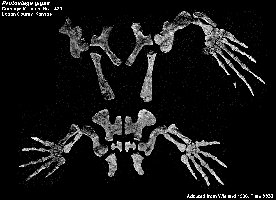

LEFT: Plate XXXI from Wieland 1906 showing

the appendicular skeleton of Protostega gigas Cope (Carnegie Museum

No. 1420) in dorsal view as collected by Charles Sternberg from near

Elkader in Logan County, Kansas.

RIGHT: Plate XXXII from Wieland 1906 showing a closer, dorsal view

of the right rear (left) and front paddles of Protostega gigas Cope

(Carnegie Museum No. 1420) as collected by Charles Sternberg from near

Elkader in Logan County, Kansas. The Carnegie

Protostega exhibit is a composite of two specimens collected by

Charles Sternberg. |

|

|

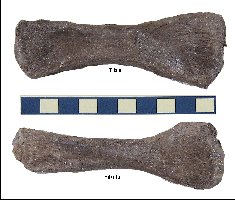

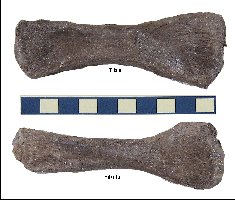

LEFT: The right humerus of the new specimen

(FHSM VP-17979) compared with a large humerus

(CMNH 1421) figured by Wieland in 1906. The adult

humerus (34 cm) is almost twice as long and much more massive as the new specimen (18 cm).. The

new humerus was found in association with possible elements of the skull.

Preparation and photo courtesy of Anthony Maltese, Triebold Paleontology,

Inc.

RIGHT: Dorsal and ventral views of the right humerus (FHSM

VP-17979).

Preparation and photo courtesy of Anthony Maltese, Triebold Paleontology,

Inc. |

|

|

LEFT: The right femur of the juvenile Protostega

gigas (FHSM VP-17979).

Preparation and photo courtesy of Anthony Maltese, Triebold Paleontology,

Inc.

RIGHT: The right tibia and fibula of the turtle (FHSM VP-17979).

Preparation and photo courtesy of Anthony Maltese, Triebold Paleontology,

Inc. |

|

|

The turtle specimen (FHSM VP-17979) is now in the preparation lab

where the bones will be cleaned and repaired for casting and

reconstruction. Stay tuned for updates!

LEFT: The reconstruction of FHSM VP-17979 in left oblique

view. Photo courtesy of Triebold Paleontology.

RIGHT: The reconstruction of FHSM VP-17979 in ventral view. Photo

courtesy of Triebold Paleontology. |

|

Other Protostega specimens:

The following information was provided by Dr. Kraig Derstler of the

University of New Orleans. Kraig is one of the few people currently studying

protostegid turtles.

"Very little is written about Protostegids, other than the

descriptive stuff by Wieland and his colleagues in the 1890's and earliest

1900's. Protostega is a huge-headed sea turtle. The species are pretty

poorly defined at present. Specimens come from the Niobrara of Kansas, the

Pierre of Kansas, Colorado, Wyoming, and South Dakota, the Mooreville,

Demopolis, and Eutaw formations of Alabama and Mississippi, and the Campanian -

Santonian marls of Texas. Possible scraps also come from other

Santonian-lowermost Maastrichtian deposits around the world. Other Protostegids

(Calcarichelys, Chelosphargis, and a couple of unnamed things)

range from the Albian through the latest Maastrichtian worldwide.

Archelon ischyros has a normal-sized skull, proportionally much

smaller than Protostega. However, it has that distinctive hooked snout.

It is so far confirmed only from the upper half Pierre in South Dakota. (Reports

from Colorado and elsewhere are pretty unbelievable.)

I've never seen any Niobrara Protostega material from an

animal that was more than about 2-2.5 m long. Niobrara giants may have existed,

but I haven't seen any evidence. And, I've never seen any signs of Archelon in

the Niobrara. However, there are lots of small to medium-size Chelosphargisspecimens and possibly some pieces of the "thorny Protostegid" Calcarichelys".

|

Dr. Kraig Derstler - "Concerning

size, the largest Protostega is a 3.4 m beast in the Dallas Museum of Natural

History. I was consultant for this exhibit and I'm pretty confident of the identification

as well as the size. The Yale Archelon is 3.0-3.1 m, but another I've studied is

4.6 m long! It is virtually perfect and articulated. As a result, the size and the

identification are both solid."

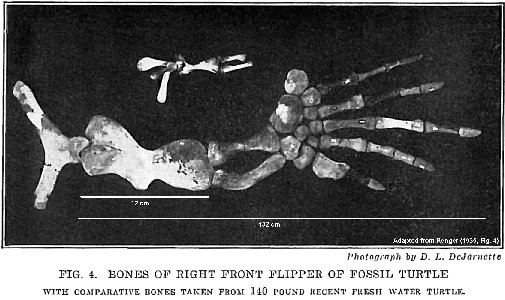

LEFT: A cast of the Dallas Protostega gigas in the McWane Center, Birmingham, AL.

(Cast by Triebold Paleontology). A view of the underside of the skull is HERE

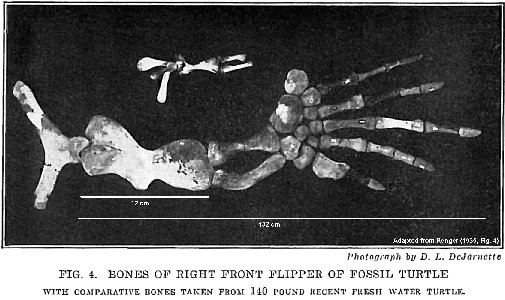

RIGHT: The right

front limb of a Protostega gigas turtle discovered in the

Cretaceous of Greene County, Alabama in 1933 (from Renger 1935). The

humerus is 42 cm long and came from an animal with a shell length of 150

cm (5 ft). Renger estimated that the animal when alive would have weighed

2.5 to 3 tons. |

|

|

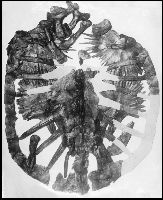

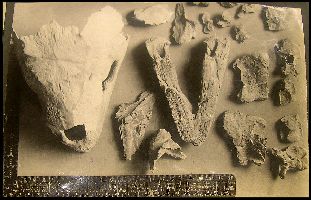

LEFT: The partial carapace and plastron on a large Protostega

gigas collected and prepared by George F. Sternberg (USNM 4886-A) and later acquired by

the United States National Museum (Smithsonian). Sternberg noted that the specimen

was found without limbs or skull.

RIGHT: The skull, lower jaw and other

fragments from another Protostega specimen that was collected by George Sternberg

in the 1920s and sent to the University of Nebraska State Museum. It is probably the same

specimen as shown below. Both photos from Sternberg archives, Forsyth Library, Fort Hays

State University. |

|

|

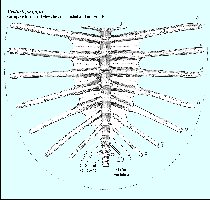

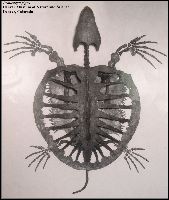

LEFT: A wall-mounted reconstruction of the partial remains of a Protostega gigas turtle in ventral view at the University of Nebraska State Museum.

Collected by George F. Sternberg.

RIGHT: The skull of the turtle shown

at left in right lateral view. Note that Protostega lacks the large bony

extension of the beak (premaxilla) found in Archelon. |

|

|

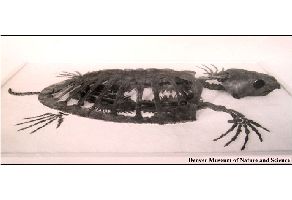

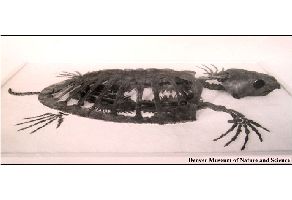

LEFT: The exhibit specimen of Protostega gigas in the

Denver Museum of Nature and Science. This specimen was collected by George F. Sternberg

(GFS 101-45) in September, 1945 from Logan County.

RIGHT: Left lateral view of the skull of the exhibit

specimen in the Denver Museum of Science and Nature. Click

here for an original photo of the skull. |

|

|

LEFT: Photograph (circa 1945) by George F. Sternberg of the above

Denver Museum Protostega gigas in dorsal view. As described by Sternberg, this

was probably a juvenile turtle with a shell that is about 3'8" wide... and a length

of about 5 feet from tip of beak to the back edge of the carapace

RIGHT:

Right lateral view of the same specimen as prepared and photographed by G.F.

Sternberg about 1945. Sternberg's field number on this specimen was 10145 (the 101st

specimen he collected in 1945). The specimen is about 5 feet in length, with a maximum

shell width of 44 inches. Sternberg also noted that the skull was 16 inches long. |

|

|

LEFT: An early photo by C.H. Sternberg of Protostega gigas from the chalk of western Kansas. The specimen is actually a composite of two

specimens (CMNH #1420 and #1421), both discovered by Sternberg about "three miles

northwest of Monument Rock" in western Gove County in 1903 and acquired by the Carnegie Museum of Natural

History in Pittsburgh, PA in 1904. Sternberg (1906) noted that this specimen

measured 10 feet (3 m) across the front paddles. A more recent picture is HERE.

RIGHT: A dorsal view of a Protostega

gigas (FHSM VP-79) carapace and plastron on exhibit at the Sternberg Museum of Natural

History. This badly flattened specimen was collected by George

Sternberg in 1930 (GFS 2-30), southeast of Gove in Gove County.

According to Sternberg/s notes, it was upside down when collected. The

shell is 40 inches across and 36 inches long. There was no skull and only

fragments of the limbs in association with the shell. The specimen

was purchased by FHSU. Side view |

|

|

LEFT: An oblique frontal view of the cast of FHSM

VP-17979, courtesy of Anthony Maltese, Triebold Paleontology, Inc.,

showing the very reduced skeletal structure of the carapace.

RIGHT: The

carapace of CMNH 1421 in ventral view from Wieland (1906, fig. 2), showing

the dorsal vertebrae and the very limited extent of the costal plates

(less than 1/3 the length of the ribs). The distal ends of the ribs fit

into depressions on the inside of the marginals, but are not fused there. |

|

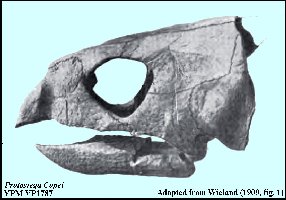

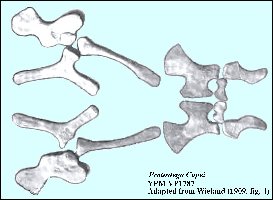

Microstega (Protostega) Copei - The

type specimen of Protostega copei (YPM VP 1787) was collected by Charles Sternberg from along Hackberry Creek in Gove County,

Kansas. It was named and first described by Wieland in 1909. Later, Zangerl (1953)

changed the genus name to Archelon, and Hooks (1998) redescribed it again

as Microstega.

Chelosphargis (Protostega) advena Hay- The type specimen of Protostega advena (KUVP

1219) was described by Hay (1908). It was collected by S.W. Williston in 1891,

probably from Gove County. While showing some protostegid characters, it is a

relatively small individual with only a little cranial or limb material present

in the specimen. The genus name was changed to Chelosphargis by Zangerl

in 1953.

|

LEFT: The remains of the type specimen of Chelosphargis

advena (KUVP 1219) as

figured by Hay in 1908.

RIGHT: Photograph of the type specimen of Chelosphargis advena (KUVP 1219) in the

University of Kansas Museum of Natural History. |

|

SUGGESTED REFERENCES:

Agassiz, L. 1849. [Remarks

on crocodiles of the Green sand of New Jersey and on Atlantochelys].

Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 4:169.

Baur, G. 1896. Ueber die Morphologie des

Unterkiefers der Reptilien. Anatomischer Anzeiger 11:410-415.

Baur,

G. 1896. Bemerkungen über die Phylogenie der Schildkröten. Anatomischer

Anzeiger 12:561-570.

Beamon, J.C. 1999. Depositional environment and

fossil biota of a thin clastic unit of the Kiowa Formation, Lower Cretaceous

(Albian), McPherson County, Kansas. Unpublished MS Thesis, Fort Hays State

University, Hays, KS, 97 pp. (oldest reported Cretaceous turtle remains in

Kansas)

Carrino,

M.H. 2007. Taxonomic comparison and stratigraphic distribution of Toxochelys(Testudines: Cheloniidae) of South Dakota. pp. 111-132 in Martin, J.E. and Parris D.C. (eds.), The Geology and Paleontology of the Late Cretaceous Marine

Deposits of the Dakotas. Geological Society of America, Special Paper 427.

Case, E.C. 1897. On the osteology and

relationship of Protostega. Journal of Morphology 14:21-60, pl. 4-6.

Case, E.C. 1898. Toxochelys. The

University Geological Survey of Kansas 4:370-385. pls. 79-84.

Cope, E.D. 1870. Observations on the Reptilia of

the Triassic formations of the Atlantic regions of the United States.

Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 11(84):444-446. (includes the

description of Pneumatoarthrus peloreus, a senior synonym of Archelon,

Wieland 1896).

Cope, E.D. 1871. A description of the genus Protostega,

a form of extinct Testudinata . Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 12(86):422-433.

Cope, E.D. 1872. [Sketch of an expedition in the

valley of the Smoky Hill River in Kansas]. Proceedings of the American

Philosophical Society 12(87):174-176. (meeting of October 20, 1871)

Cope, E.D. 1872. On a new Testudinate from the

chalk of Kansas. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society

12(88):308-310. (Cyanocercus incisus )

Cope, E.D. 1872. A description of the genus Protostega,

a form of extinct Testudinata. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society

12(88):422-433. (March 1, 1872)

Cope, E.D. 1872. On the geology and paleontology of

the Cretaceous strata of Kansas. Annual Report of the U. S. Geological Survey of

the Territories 5:318-349 (Report for 1871).

Cope,

E.D. 1872. [On a species of Clidastes and Plesiosaurus guloCope]. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 29:127-124

Cope, E.D. 1873. [On Toxochelys latiremis].

Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 25:10.

Cope, E.D. 1875. The Vertebrata of the Cretaceous

formations of the West. Report, U. S. Geological Survey Territories (Hayden).

2:302 p, 57 pls.

Cope, E.D. 1877. On some new or little known

reptiles and fishes of the Cretaceous of Kansas. Proceedings of the American

Philosophical Society 17(100):176-181. (Toxochelys latiremis Cope: issue

of May-Dec., 1877, printed Nov. 20, 1877)

Dollo, L. 1887. Le hainosaure et les nouveaux vertébrés

fossiles du Musée de Bruxelles. Revue des Questions Scienfiques XXI 504-539.

(April 1887)

Dollo, L. 1887. Le hainosaure et les nouveaux vertébrés fossiles du Musée de

Bruxelles. Revue des Questions Scienfiques XXII 70-112. (July 1887)

Druckenmiller, P. S., A. J. Daun, J. L. Skulan and

J. C. Pladziewicz. 1993. Stomach contents in the upper Cretaceous shark Squalicorax

falcatus. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 13(supplement. to no. 3):33A.

Elliott, D.K., Irby, G.V. and Hutchinson, J.H.

1997. Desmatochelys lowi, a marine turtle from the Upper Cretaceous. pp.

243-258 in Callaway, J.M. and Nicholls, E.L. (eds.). Ancient Marine Reptiles,

Academic Press, San Diego.

Everhart, M.J. and Pearson, G. 2008. First report on a

marine turtle from the Fairport Chalk Member of the Carlile Shale of Mitchell

County, Kansas. Kansas Academy of

Science, Transactions 112(1-2):138-139

(Abstract).

Gaffney, E. S.

1972. An

illustrated glossary of turtle skull nomenclature. American

Museum Novitates 2486:1-33.

Gudger, E.W. 1949. Natural history notes on tiger sharks, Galeocerdo

tigrinis, caught in Key West, Florida with emphasis on food and feeding

habits. Copeia 1949: 39-47, pl. 1-2.

Hay, O. P. 1895. On certain portions of the skeleton of Protostega

gigas. Publ. Field Columbian Museum, Zoological Ser. (later Fieldiana:

Zoology), 1(2):57-62, pls. 4 & 5.

Hay, O. P. 1896. On the skeleton of Toxochelys

latiremis. Publ. Field Columbian Museum, Zoological Ser. (later Fieldiana:

Zoology), 1(5):101-106, pls. 14 &15.

Hay, O.P. 1903. A revision of the

species of the family of fossil turtles called Toxochelyidae, with descriptions

of two new species of Toxochelys and a new species of Porthochelys.

Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 21(10):177-185.

Hay, O.P. 1905. A revision of the species of the family

of the fossil turtles called Toxochelyidae with descriptions of two new species

of Toxochelys and a new species of Porthochelys. American Museum of Natural History Bulletin 21:177-185.

Hay, O. P. 1908. The fossil turtles of North

America. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Publication No. 75, 568 pp, 113 pl.

Hirayama,

R. 1997. Distribution and diversity of Cretaceous cheloniods. pp. 225-241 in

Callaway, J.M. and Nicholls, E.L. (eds.), Ancient

Marine Reptiles, Academic Press, San Diego.

Hooks, G. E., III. 1998. Systematic revision of the

Protostegidae, with a redescription of Carcarichelys gemma Zangerl, 1957.

Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 18(1):85-98.

Kear, B.P. 2006.

First gut contents in a Cretaceous sea turtle. Biological Letters 2:113-115.

Konuki, R. 2008.

Biostratigraphy of sea turtles and possible bite marks on a Toxochelys (Testudine,

Chelonioidea) from the Niobrara Formation (Late Santonian), Logan County, Kansas

and paleoecological implications for predator-prey relationships among large

marine vertebrates. Unpublished

Masters thesis, Fort

Hays

State

University

, Hays, Kansas, 141 pp, App. I-VI.

Lane, H.H. 1946. A survey of the fossil vertebrates

of Kansas, Part III, The Reptiles, Kansas Academy Science, Transactions

49(3):289-332, 7 figs.

Leidy, J. 1865. Cretaceous reptiles of the United

States. Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge 14(192):1-135, pls. 1-20.

Manning, E.M. 1994. Dr. William Spillman

(1806-1886), pioneer paleontologist of Mississippi. Mississippi Geology

15(4):64-69.

Matzke, A.T. 2007. An almost complete juvenile

specimen of the cheloniid turtle Ctenochelys stenoporus (Hay, 1905) from

the Upper Cretaceous Niobrara Formation of Kansas, USA. Palaeontology 50(3):669-691.

Matzke,

A.T. 2008. A juvenile Toxochelys latiremis (Testudines, Cheloniidae) from the Upper

Cretaceous Niobrara Formation of Kansas, USA. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie. Abhandlungen

249(3):371-380.

Matzke, A.T. 2009. Osteology of the skull

of Toxochelys (Testudines,

Chelonioidea) (with 25 text-figures). Palaeontographica Abteilung A

288(4):93-150.

Mulder, E.W. A. 2003. On latest Cretaceous tetrapods from the

Maastrichtian type area. Publicaties van het Natuurhistorisch Genootshap in

Limburg, Reeks XLIV, aflevering 1.Stichting Natuurpublicaties Limburg,

Maastricht.

Nicholls, E.L. 1988. New material of Toxochelys

latiremis Cope, and a revision of the genus Toxochelys (Testudines,

Chelonoidea). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 8(2):181-187.

Nicholls, E.L., Tokaryk, T.T. and Hills, L.V. 1990. Cretaceous

marine turtles from the Western Interior Seaway of Canada. Canadian Journal

Earth Sciences 27:1288-1298.

Nicholls,

E.L. 1992. Note on the occurrence of the marine turtle Desmatochelys (Reptilia:

Chelonioidea) from the Upper Cretaceous of Vancouver Island. Canadian

Journal of Earth Sciences 29:377-380.

Renger, J.J. 1935. Excavation of Cretaceous

reptiles in Alabama . Science Monthly 41:560-565.

Roth, D.D. and Everhart, M.J.

2012. Preparation of a protostegid turtle from the Fairport Chalk (Carlile

Formation, Late Cretaceous). Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions

115(1-2):71-72.

Russell, D. A. 1993.

Vertebrates in the Western Interior Sea. Pages 665-680 in Caldwell, W. G.

E. and E. G. Kaufmann, eds., Evolution of the Western Interior Basin, Geological

Association of Canada, Special Paper 39.

Shimada, K., M.J. Everhart, and G. E. Hooks. 2002.

Ichthyodectid fish and protostegid turtle bitten by the Late Cretaceous

lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli. Journal of Vertebrate

Paleontology 22(supplement. to 3):106A. (Abstract)

Sternberg, C.H. 1884. Directions for collecting

vertebrate fossils. Kansas City Review of Science and Industry 8(4):219-221.

Sternberg, C.H. 1899. The

first great roof. Popular Science News 33:126-127, 1 fig.

Sternberg, C.H. 1905. Protostega gigas and

other Cretaceous reptiles and fishes from the Kansas chalk. Kansas Academy

Science, Transactions 19:123-128.

Sternberg, C.H. 1906. Some

animals discovered in the fossil beds of Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science,

Transactions 20:122-124.

Sternberg, C.H. 1907. My

expedition to the Kansas Chalk for 1907. Kansas Academy of Science,

Transactions 21:111-114.

Stewart, J.D. 1978. Earliest record of the

Toxochelyidae. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 81(2):178 (abstract).

Stewart, J.D. 1990.

Niobrara Formation vertebrate stratigraphy, pages 19-30, In Bennett, S. C.

(ed.), Niobrara Chalk Excursion Guidebook, The University of Kansas Museum

of Natural History and the Kansas Geological Survey.

Wagner, G. 1898. On

some turtle remains from the Fort Pierre. Kansas University Quarterly

7(4):201-203.

Wieland, G.R. 1896. Archelon ischyros: a new

gigantic cryptodire testudinate from the Fort Pierre Cretaceous of South Dakota.

American Journal of Science, 4th Series 2(12):399-412, pl. v.

Wieland, G.R. 1900. Some observations on certain

well-marked stages in the evolution of the testudinate humerus. American Journal

of Science, 4th Series, 9(54):413-424, with 23 text fig.

Wieland, G.R. 1902. Notes on the Cretaceous

turtles, Toxochelys and Archelon, with a classification of the

marine Testudinata. American Journal of Science, Series 4, 14:95-108, 2

text-figs.

Wieland, G.R. 1903. Notes on the marine turtle Archelon. I. On the structure of the carapace, II. Associated fossils.

American Journal of Science 15:211-216.

Wieland, G.R. 1905. A new Niobrara Toxochelys.

American Journal of Science, 4th Series, 20(119):343, pl. x, 8

text-figs.

Wieland, G.R. 1906. The osteology of Protostega.Memoirs of the Carnegie Museum, 2(7):279-305.

Wieland, G.R. 1909. Revision of the

Protostegidae. American Journal of Science, Series 4. 27(158):101-130,

pls. II-IV, 12 text-figs.

Williston, S.W. 1894. A new turtle from the Benton Cretaceous.

Kansas. University Quarterly 3(1):5-18, with pl. II-VI.

Williston, S.W. 1898. Turtles. The University

Geological Survey of Kansas, Part VI. 4:349-369. pls. 73-78.

Williston, S.W. 1901. A new turtle from the Kansas

Cretaceous. Kansas Academy Science, Transactions 17:195-199.

Williston, S.W. 1902. On the hind limb of Protostega. American

Journal of Science, Series 4, 13(76):276-278, 1 fig.

Williston, S.W. 1914. Water reptiles of the past and present. Chicago

University Press. 251 pp.

Zangerl, R. 1953.

The vertebrate fauna of the Selma formation of Alabama, Part IV, the turtles of

the family Toxochelyidae. Fieldiana (Geology Memoirs): 3(4): 137 - 277.

Zangerl, R. 1980. Patterns of phylogenic

differentiation in the toxochelyid and chelonid sea turtles. American Zoologist

20:585-596.

Zangerl, R. and Sloan, R.E. 1960. A new description

of Desmatochelys lowi (Williston). A primitive cheloniid sea turtle from

the Cretaceous of South Dakota. Fieldiana, Geology Memoirs 14:7-40.