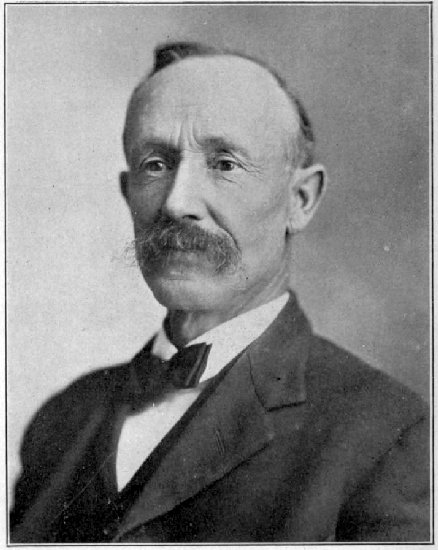

Charles H. Sternberg

Fossil Hunter

1850-1943

Copyright © 2004-2014 by Mike Everhart

ePage created 10/13/2004; Last updated 02/05/2014

LEFT: Photograph of Charles H. Sternberg from the Frontispiece of his 1909 book, Life of a Fossil Hunter

Charles Hazelius Sternberg was born in 1850 near Cooperstown, New York. He and his twin brother, Edward, moved to Kansas in 1867 and lived for several years on a ranch 2 miles south of Fort Harker (Kanopolis, Kansas) that was owned by their older brother, Dr. George M. Sternberg, the Army surgeon at Fort Harker. Charles started out collecting leaf imprints from the Dakota Sandstone exposures near the ranch. During the winter of 1875-76, he was a student at the Kansas State Agricultural College (now Kansas State University) but was unable to secure a place on B. F. Mudge's fossil collecting crew in the summer of 1876. He then sent a letter to E. D. Cope seeking employment as a fossil collector and Cope replied in a note with a check for $300 and instructions to "Go to work." One of the first specimens he collected for Cope in 1876 was a series of 23 large Tylosaurus? vertebrae [AMNH FR 1589]. He worked for Cope for four years the first time, and was working for him when Cope died in 1897. From that beginning, Charles Sternberg and his sons, George, Charles and Levi went on to become famous as fossil collectors.

The

Sternberg Family

Rev. Levi Sternberg |

|

Charles H. Sternberg was the son of Levi Sternberg (Feb. 16, 1814 - Feb. 13, 1896) and Margaret Levering Miller (b. 1818, d. Dec. 9, 1888). Levi and Margaret were married on Sept. 7, 1837 and had eleven children, nine sons, including twins (Charles Hazelius and his brother, Edward Endress), and two daughters. Their first child, George Miller Sternberg (June 8, 1838, d. Nov. 3, 1915) was a military doctor during the Civil War, served at Fort Harker, Kansas in the late 1860s, and went on to become the Surgeon General of the United States Army during the Spanish-American War. General George M. Sternberg is buried in Arlington National Cemetery, Washington, DC. Their second child, Theodore Sternberg (Sep. 15, 1840 - Jan. 5, 1927), served in the Union Army during the Civil War and retired as a Major. He and his wife are buried in the the Buckeye Cemetery near Kanopolis, Kansas. John Frederick Sternberg (Mar. 12, 1843 - Feb. 16, 1928) also served in the Union Army and is buried in the Buckeye Cemetery. Levi and Margaret Sternberg are buried in the old Ellsworth Cemetery, Ellsworth, Kansas. Edward

did not share his brother's interest in fossil hunting. Edward married

Lydia Ellen Griffith on Jan. 19, 1879. They had 7 children. He opened a

cheese factory in Holyrood, KS, and later became a Methodist minister. He

died in Little Rock, Arkansas, June 28, 1921 at the age of 71. Charles (b. June 15, 1850, d. July 21, 1943) married Anna Musgrove Reynolds (b. March 5, 1853, d. Dec. 24, 1938) on July 7, 1880. They had five children, Charles Reynolds Sternberg (b. 1881), died before his second birthday, George Fryer (b. Aug. 26, 1883, d. Oct. 23, 1969), Charles Mortram (b. Sep. 11, 1886, d. Sep. 4, 1981, Ottawa, Canada), Maude (b. Oct. 30, 1890, d. Jan. 15, 1911, Lawrence, Kansas) and Levi (b. March 10, 1894, d. Oct. 21, 1976, Toronto, Canada). George F. Sternberg married Mabel Smith on December 31, 1907. They had three children, Charles W. (Oct. 18, 1908- June 26, 1994), Margery Anna (Nov. 25, 1909 - Nov. 21, 1911) and Ethel May (1913- ). Margery died in Lawrence, Kansas and is buried there. George and Mabel were divorced in 1926. George married a widow, Anna Reed Ziegler in 1930. George and Anna are buried in the Mount Allen Cemetery in Hays, Kansas. Mabel Sternberg moved to Chicago with her two children and George stayed in Kansas. Charles W. Sternberg helped his father collect fossils as a teenager, much the same as George Sternberg had worked on fossils with his father, and is credited with making several significant discoveries, including the 30 ft Tylosaurus proriger specimen (FHSM VP-3) currently on exhibit at the Sternberg Museum of Natural History in Hays, Kansas. However, his heart wasn't in paleontology and he went on to study geology at the University of Chicago. While he was in college in Chicago, Charles W. Sternberg married Alta Marie Holloway (b. July 10, 1913 - d. Dec. 26, 1998). Charles graduated from college with a degree in geology and later worked as a field geologist in Turkey and Israel, as well as the United States. G.F. Sternberg was living in a care facility at the time of his death in 1969, and was buried in the Mt. Allen Cemetery in Hays, Kansas. Charles and his wife, Alta, lived out their years in Carolina Beach, North Carolina and are presumed to be buried there. |

While certainly not the model of a well-educated, 19th Century gentleman paleontologist (E. D. Cope and O. C. Marsh come to mind here), Charles Sternberg added a different dimension to the relatively new science of paleontology and left a legacy of spectacular fossil discoveries that are found in museums around the world today. The following passages are taken from some of C. H. Sternberg's published papers, and his two books.

This page is not intended to be a complete biography of Charles Sternberg, but rather a collection of some of his fossils and his stories / impressions. See the obituary at the bottom of the page for more background regarding his life. The best source for information concerning Charles Sternberg and his sons is:

Rogers, Katherine. 1991. A dinosaur dynasty: The Sternberg Fossil Hunters. Mountain Press Publishing Company, 288 pages. |

--------------------------0-------------------------------

Click on link to access the complete list of ePapers on Oceans of Kansas

| The Niobrara Group (1881):

"Of all the strange animal forms found in the rich, fossiliferous beds of western

Kansas, I think Cope’s Protostega gigas, or marine tortoise, is the most

unique. Cope calls them the boatmen of the cretaceous ocean. |

Directions for collecting vertebrate fossils (1884):

"The proper outfit for a collecting expedition consists of a good team of ponies or small mules, a light lumber wagon, cover, wall-tent, camp-stove or "Dutch oven," knives and forks, tin plates and cups, and other cooking-utensils. Each member of the party should be provided with a rubber blanket and coat, and a couple of pairs of woolen blankets; besides these but little extra baggage should be taken; a good pair of woolen shirts are valuable. The tools should consist of several small hand-picks, miner's-picks, with one point made into a duck-bill with sharp edge; butcher-knives, shovels and collecting-bags --- made after the pattern of mail-carrier's bags, of heavy ducking, with two apartments - one for cotton, paper and string, and the other for fossils. There should always be kept on hand a supply of burlap sacks, old newspapers, cotton, manila paper and hop-needles; boxes and barrels for shipping."

|

Ancient monsters of Kansas (1898): "...the sun above us darkened by the wings of great flying dragons, who flap their leathery pinions over the bay, or with broad expanded wings, 20 feet from tip to tip, rest motionless upon the air. Their heads 4 ft. in length, terminate in long bony toothless beaks; their large powerful eyes are watching the depth below; a luckless fish attracts the monster’s attention and with fearful speed he dashes into the blue water and reappears with the poor fish which rapidly disappears down his cavernous throat; then he resumes his majestic circles and watches for another victim."

|

| The first great roof (1899): "Professor Cope, from his own fertile brain, created the genus Protostega, and described the type species gigas, from the material he dug with such infinite care and patience from the chalk of Butte Creek, Logan Co., Kansas, in 1871, and in his laboratory with his own hands put together the broken fragments of the friable bones (a task of patient endurance few men are capable of). He showed his intense interest in the greatest of all sea tortoises. I doubt not that as he restored the fragile bones piece by piece, and they began to grow under his skillful hands, he was carried away with the idea of so many paleontologists of that time, and of many to this day, namely, that from a few bones of the skeleton he could restore the whole structure as it appeared in life." |

| A Kansas mosasaur (1899): "There

are three well-defined genera of the Mosasaurs found in the chalk of western Kansas. The

giant of his race, Tylosaurus,

reached a length of nearly 50 feet. The next in point of size and power was the genus Platecarpus, with four

broad paddles. The last is Clidastes,

a smaller and more elegantly built reptile, with well developed additional articulations

in the vertebral column, that enabled it to coil up like a serpent. All these reptiles had

long conical heads terminating in a heavy, bony snout. In Platecarpus this is blunt, but in the other genera

they are long and conical; and Cope believed they were used as a battering ram against

their foes. |

| Fossil collector's experiences (1900): "

... Cope’s Protostega gigas, “the first great roof,”—The

largest of all sea turtles.

|

| The sharks of Kansas 1900): "This will prove, also, of great interest to science, as this specimen belonged to another genus [Squalicorax] from the one mentioned above. The teeth are broad and flat, slightly recurved, with delicately serrated edges And it represents, I believe, the second best specimen so far taken from the Chalk of Kansas, or the Niobrara Group of the Cretaceous. These teeth range in size from less than ¼ to 7/8 of an inch across the roots, one measuring 1 1/8 inches from recurved point to end of opposite root. There are 132 teeth preserved, some so small as to be hardly visible, others quite large; some are evidently young ones. These beautiful teeth during life must have been used with scissor-like action, cutting the living prey finer then any modern meat-cutter."

|

| Protostega gigas and other

Cretaceous reptiles and fishes from the Kansas chalk [1905] "In his report to the United States Geological Survey of the Territories, volume II, 1875, Prof. E. D. Cope fully describes the material on which he founded the new genus Protostega. To me, after all these years, having collected many specimens of this large tortoise, it has been a wonder how he was able, from the bones he collected himself and restored with infinite care and patience, to make such a nondescript of the animal, especially as in volume IV he gives, as the most important law that governs paleontology, “the persistence of type.” But this creature, as he created it, is an exception to the rule. He makes the total length 12.83 feet, with width of carapace -three feet and length seven feet, or twice as long as wide. One mistake leads to another. The professor thought the skeleton he discovered lay on its back. The loose ribs doubtless did, as their heads were pointed upward. During the time it was being buried in the soft sediment they could easily have been turned over. I have found hundreds of specimens where the elements have been macerated free from their fellows, and lying in every conceivable position; in fact, it is rare indeed to find them in their natural position." |

|

Some animals discovered in the fossil beds of Kansas (1906):

"For many years past the writer of this paper has given his entire time to the collection and preparation for exhibit of fossils from several Western states, giving much time to the rich fields of western Kansas, so prolific in fine examples of ancient vertebrate life. Some mention of some of the best finds made within the last few years and where these have gone, many being lost forever for any Kansas museum, is worthy of record. A complete skeleton of a new plesiosaur [Type of Dolichorhynchops osborni, KUVP 1300] was found by the writer's son on the Hathaway ranch, on Beaver creek, Logan county, and which is now in the museum of the University of Kansas, having been mounted by the very competent preparator, Mr. H. T. Martin. A nearly complete skeleton of Portheus colossus [sic], of Cope, collected on Robinson's cattle ranch, in Logan county, within stone's throw of the stable, is now mounted in the American Museum, at New York, and is said to be the best example of a fossil fish in any museum in the world."

|

My expedition to the Kansas Chalk for 1907:

"Another fine specimen sent from the field was a complete skull, with mandibles, of a new species of the Cretaceous sea-tortoise Toxochelys. This I believe belongs to the new species of which I sent to Yale a couple of years ago a nearly complete carapace and plastron, described by Doctor Wieland as Toxochelys bauri [YPM 3601, 3603]. The skull and mandibles are more robust than the principal species, Cope’s T. latiremis, wider at the nasal bones, and with round orbits, instead of oblong, as in latiremis. The sagittal crest is larger and sculptured."

|

An armored dinosaur from the Kansas chalk (1909):

"In 1905, while conducting an expedition in the Kansas Chalk, I discovered the broken-up skeleton of what I considered a large new sea-tortoise with an ossified carapace. It attracted my attention, and I knew it was new, but as it was weathered and detached from its matrix I concluded it could not be used and left it there. Later, my son George brought into camp, a few miles from Hackberry creek, where I had found my specimen, some peculiar plates like the ones I have already mentioned; but as I had no knowledge of Barnum Brown's discovery, I concluded they were the neurals of a new turtle. These I sent on to Dr. G. R. Wieland for description. Last month I was his guest at Yale University museum. He asked me why I thought it a new turtle. After giving my reasons, he told me it was new enough, but these plates were the dermal scutes of an armored dinosaur. Later I secured the skeleton [YPM 1847], through the efforts of my son, who found them as I directed." |

--------------------------0-------------------------------

Life of a Fossil Hunter (1909, p. 25-27):

"In 1897, I spent 3 months in the Dakota Group...I secured over 3000 leaves and paid

first-class freight on them to my home in Lawrence. There I worked from November to May,

standing on my feet on an average of fourteen hours a day. At night I worked over a coal

oil lamp. With a number 1 needle [I] pried away the stone from the petioles, leaving the

impression as if it were the leaf itself standing up in bold relief... One of my

neighbors remarked, "You must have taken a long time to carve those things. Why, they look just like leaves!"

|

Life of a Fossil Hunter (1909, p. 113-114):

"This is the first time and, I believe, the only time that so complete a specimen of this ancient shark has been discovered. The column and other solid parts were composed of cartilaginous matter which usually decays so easily that is rarely petrified. I suppose my specimen was old at the time of its death, and bony matter had been deposited in the cartilage. It is not very likely that such a specimen will ever be duplicated. Dr. Eastman's [1895?] study of this skeleton enabled him to make synonyms of many species which had been named from teeth alone." According to Sternberg, "the most complete skeleton of the Cretaceous shark, Oxyrhina mantelli [Cretoxyrhina mantelli] Agassiz ever discovered in any formation" was sold to the "Ludwig-Maximilian University of Munich." |

The Life of a Fossil Hunter (1909, p. 114)

"In 1903, I was so fortunate as to find a practically complete skeleton of Protostega gigas in normal condition, that is, with the bones all in or near their original positions."

LEFT: Protostega gigas: A photo by C. H. Sternberg of a mounted specimen of Protostega gigas from the chalk of western Kansas. The specimen is in the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, PA. This is a composite of #1420 and #1421, both discovered by Sternberg about "three miles northwest of Monument Rock" in western Gove County in 1903 and acquired by the Carnegie Museum in 1904. (Length ~ 3 m) A more recent picture is HERE. Sternberg (1906) noted that this specimen measured 10 feet (3 m) across the front paddles. |

The Life of a Fossil Hunter (1909, p. 265-266)

"Unfortunately, the skull is missing, otherwise the nearly complete specimen is present, and strange to say in normal position. ... Our specimen, however, shows a much longer neck than he [Dr. F. A. Lucas] had imagined. Strange indeed was this long-necked diver with its tarsus at right angles with the body and its powerful web-footed feet. The body was narrow, a little over four inches wide, with a backbone like the keel of a boat. The head was ten inches long and armed with sharp teeth."

LEFT: The headless skeleton of Hesperornis regalis (AMNH FR 5100) discovered by the elder Sternberg's son, Charles M. Sternberg, in 1907 in the Smoky Hill Chalk near Twin Butte Creek, Logan County, Kansas; now in the collection of the American Museum of Natural History. The sternum and ribs are also missing. |

--------------------------0-------------------------------

In the Niobrara and Laramie Cretaceous (1911):

"Our second camp proved very rich. Here we camped southwest of Banner post office, in Trego county. Some photographs I exhibit show some sculptured towers near Castle Rock, a few miles west of our camp. George discovered a fine skeleton of a great flying reptile Pteranodon. This also has gone to the American Museum. One wing was complete, including the claw-armed fingers used in clinging to rocks while at rest. Our bats hang head downward, while the Pteranodons hung with head up. The crowning discovery of our work here was the discovery by George Sternberg of a nearly complete skeleton of a great shark, Lamna. In 1891, while employed by the Munich Museum, I discovered the first and most complete skeleton known of the shark Oxyrhina mantelli in the same vicinity. This was made the subject of Dr. C. R. Eastman's inaugural address delivered before the Ludwig-Maximilian University of Munich for his Ph.D. degree." |

|

Expeditions to the Miocene of Wyoming and the chalk beds of Kansas [1913]

"Of the wonderful snout fish, or Protosphyraena, of the Niobrara, George found a complete set of pectoral fins, with their arches. They

measure 3 feet and 9 inches in length and are 101 inches wide at the base. The enameled

edge is as sharp as a knife. In life they stood out at right angles to the body, like the

scythes attached to the wheels of the chariot of some ancient war king. They were rigid when they carved at pleasure the living Portheii

or mosasaurs. The premaxillæ were prolonged into a

long, dagger-like weapon of solid bone, and, the teeth in the angles of the jaws |

| Evidence proving that the Belly River beds

of Alberta are equivalent with the Judith River beds of Montana [1915] "It was difficult for me not to believe that I was in a Red Deer bone-bed, as the same material was strewn around here in Montana. In the Edmonton, however, the bones have the appearance of having once been flotsam along a sea shore at the limit of the high tide. I only found a couple of fragments of turtle shells there, while they are very abundant in this bone-bed on Taffy Creek. Everywhere in this region are two veins of coal, on top of the Judith River Beds and immediately below the Bear Paw Shales. Above each vein is an oyster bed, often three or four feet thick. In the Bear Paw Shales south of camp, with the aid of a sheepherder, Mr. Dowling found a fine new Mosasaur, evidently a Clidastes, as the chevrons are anchylosed to the centra of the vertebræ and the end of the tail is expanded into a fin. We secured the mandibles with teeth, a lot of dorsal vertebræ, and nearly 15 feet of the tail. We also collected some fine Ammonites and Baculites as well as a couple of specimens of a Plesiosaur resembling Cimoliasaurus [sic]. These fossils cannot be distinguished from similar ones we procured from the Fort Pierre above the Belly River series in the Dead Lodge Canyon on the Red Deer River. ..." ... It appears evident, too, that the life of the Pierre ocean was continuous with the Belly River, whose shores were only raised a few feet above tide water. Many Plesiosaurs found entrance to the freshwater lakes and mingled their bones with the reptilian fauna...." |

Five Years Explorations in the fossil beds of Alberta [1918]

In the early part of the year 1912, with my son George F., I went to the Victoria Memorial Museum at Ottawa, Canada, with a skeleton of a Kansas mosasaur, Platecarpus coryphaeus; a large fossil fish, Portheus molossus; and a skeleton of Titanotherium, which I discovered in the Oligocene of Niobrara County, Wyoming. The other two skeletons George found in the Kansas chalk. We mounted this material, working from March until sometime in June. We found there a great building with little original material for exhibition, chiefly casts, and a few common fossil reptiles from Europe. Doctor Brock, the director of the museum, was anxious to secure the services of myself and my sons to build up for their museum a collection of the wonderful horned, crested duckbills, and plated dinosaurs of the rich fossil beds of the Red Deer river. The Survey had discovered these beds twenty-five years before. ...

The next season [1913] I moved down the river eighty miles from Drumheller to the fresh-water deposit of the Belly river series, which is the same age as the Pierre, which lies immediately above, showing that in this region the land had been elevated above the Pierre ocean. We found Pierre plesiosaurs in the Belly river beds, showing that the rivers and bayous emptied into the sea nearby. The plesiosaurs swam inland and often left their bones to mingle with the land and swamp dinosaurs." |

Explorations of the Permian of Texas and the chalk of Kansas, 1918: (Published in 1922)

"I was so fortunate as to find a fine tylosaur skeleton the second day in the field. There were twenty-one feet of the skeleton present in fine chalk. The complete skull was crushed laterally, nearly the complete front arches and limbs were present, as was also the pelvic bones and both femora. All the vertebræ to well into the caudal region beyond the lateral spines were continuous, with the ribs in the dorsal region. Between the ribs was a large part of a huge plesiosaur with many half-digested bones, including the large humeri, part of the coracoscapula, phalanges, vertebræ, and, strangest of all, the stomach stones, showing that this huge tylosaur, that was about twenty-nine feet long, had swallowed this plesiosaur in large enough chunks to include the stomach. How powerful the gastric juice that could dissolve these big bones! This specimen I sent to the United States National Museum." |

|

Field work in Kansas and Texas [1919] (Published in 1922)

"My third camp was made at Mr. Martin’s ranch, south of Castle Rock, on the

brakes of the Smoky Hill river north of Utica. Here I was left entirely alone and had a

severe time of it. I was so fortunate, however (and that, really is what counts), as to find a

splendid skeleton of Platecarpus, with all the paddles, breastbones and

cartilaginous ribs. Only a few terminal caudal, bones were missing from the skeleton. I

found it very difficult to handle the big sections in which I took it up. There were two,

and they weighed about 500

pounds each. However, by

using all the skill I had I succeeded in accomplishing the labor of turning them over. I

have mounted this skeleton in a panel. It is 18 1/2 feet long. |

--------------------------0-------------------------------

Excerpts from C. H. Sternberg's "Hunting Dinosaurs in the Badlands of the Red Deer River, Alberta, Canada" (1917).

"In 1911, I sent George to western Kansas with a party to collect in the Chalk, and with wonderful results; for though I had secured four skeletons of the famous Tarpon-like fish of the Cretaceous, named Portheus molossus by Cope, he succeeded in finding the most complete skeleton known to science, now mounted in the British Museum of Natural History, in London. Mr. Pycraft has pictured it in the London Illustrated News for March 1, 1913. "The giant to which I refer now" (he says) , "has been dead a very long while, a million years or so [over 5,000,000 - C. H. S.]. Its remains in a most extraordinary state of preservation, will be found in the Geological Gallery. Measuring just fourteen feet in length, it must have weighed between four and five hundred pounds [a thousand likely. - C. H. S.]. It was obtained from the chalk of Kansas, and has quite a remarkable history. It was found by Professor Sternberg, who has achieved a world-wide fame for his discovery of fossil fish and his quite amazing skill in digging his finds from the rock in which they are embedded. The specimen was found [by George F. Sternberg], exposed at the surface of the ground, and was much the worse for wear and tear of wind and rain and sun. But Professor Sternberg was equal to the occasion. For just as there are two sides to every question, so there are two sides to every fossil. The resourceful discoverer determined to get at the other side of this very stale fish; for the exposed side was useless. Accordingly he covered it with a thick layer of plaster of Paris and when this was set he proceeded to dig out the fossil from the bed of chalk. This accomplished, he cut away the rock from the specimen, and eventually succeeded in exposing the whole fish." [The underside at least.- C. H. S.]" (Annotations to a story in the London Illustrated News of March 1, 1913)

"Hunting Dinosaurs in the Badlands of the Red Deer River, Alberta, Canada" (1917, p. 11-12). |

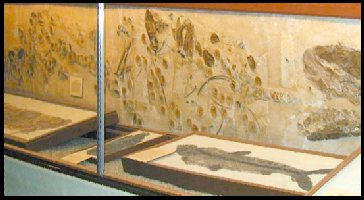

LEFT: This is a picture of a large Xiphactinus (BMNH P. 11125) in the British Museum of Natural History. The specimen was found by George Sternberg and sold to the museum by Charles Sternberg. The picture was taken by the parents of Charles Choguill, when they were in London in 1959-1960. According to Mr. Choguill, this specimen and other Kansas fossils were no longer on exhibit when he visited the BMNH in 1971. More recently (10/2007), Matt Friedman indicated that it was currently on display in the Earth Gallery (the old Museum of Geology). |

|

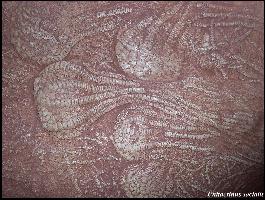

LEFT: A detail from the beautiful exhibit specimen of Uintacrinus

socialis at the Sternberg Museum. This specimen was found by George F. Sternberg in

Logan County. See other close-ups of individual crinoids in this specimen: HERE, HERE and HERE. "Their bodies were about the shape of half an egg, with an opening in the center, and ten arms radiating from the margin. These arms were three feet long, with feathered edges. Over the mouth, too, were smaller arms used to comb off into the mouth the tiny animal life of the sea, that was strained through, and caught in the meshes of the feathered arms. My boys found hundreds of these crinoids in the Chalk on Beaver Creek, Kansas, called Uintacrinus socialis. We enriched many Museums with them." Hunting Dinosaurs in the Badlands of the Red Deer River, Alberta, Canada" (1917, p. 156). |

On fossil leaves from the Cretaceous Dakota Sandstone: “… We first entered a hard and softwood forest, composed largely of Sassafras, Magnolia, Linden, Birch in endless variety, Cinnamon, Sweet Gum, and many others of the first trees with heart and bark like our existing forests of the twentieth century. There was a thick underbrush of wild roses and aralia vines, with their beautiful three and five lobed dentate leaves. The brooks were lined with rushes, ferns and other familiar vegetation. … see the damp sand along the river shore? See how the leaves have fallen into it; some lie flat, others, with stem down, are half buried; all will be covered with the ocean mud at high tide, and there they will remain until pressed by the masses of rock that will be laid down upon the deposit, which will be hardened into sandstone, and the leaf impressions will be preserved for millions of years. Until in the twentieth century, I will dig them from the solid rock in the central plains of Kansas, and Lesquereux and Ward, and Knowlton and Wilson will identify them."

"Hunting Dinosaurs in the Badlands of the Red Deer River, Alberta, Canada (1917, p. 156-157). |

|

LEFT: Skull of KUVP 247 in the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History

"The Portheus [Xiphactinus audax], now swimming for life, was the foci of the sharks that were coming to the attack from all directions. One would dive under the fish, and receive, for his pains, a stroke from his powerful tail that would put him out of commission; another would receive a thrust from the sword-like ray of the front fin. Undaunted, others hurried up like a pack of wolves on a wounded deer. Though many were wounded in the fray, our hero fish at last succumbed to numbers, who gashed his body with their lance-like teeth, and the water was tinged with his life blood, until, weakened and overpowered, he gradually ceased struggling. The sharks gathered to the feast. One, however, was so badly wounded by the Portheus, that he went to the oozy bottom with him. I have preserved in the Museum of the University of Kansas a shark twenty-five feet long, and mingled with his remains were the bones of a Portheus, the evident result of such a combat …" "Hunting Dinosaurs in the Badlands of the Red Deer River, Alberta, Canada" (1917, p. 162). |

|

LEFT: While the passage above from C H.

Sternberg's book is fiction, it is based on George F. Sternberg's discovery of the remains

(KUVP 247) of a large Cretoxyrhina mantelli (Ginsu shark) in Trego County that also

contains the scattered bones of a large Xiphactinus as its last meal. The specimen

is on exhibit in the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History in Lawrence, Kansas.

Here is a close-up of some of the teeth in that specimen.

Larger view of the Xiphactinus remains found inside the shark |

|

On Protosphyraena: “… I used to think that the

man-eating sharks off the Florida coast were the most blood-thirsty of the order, but this

one is still worse. Notice the head is prolonged in front into a long round bony snout, or

ram. On account of this, I called it a snout fish, when I first discovered their bones in

the Kansas Chalk. The ram ends, you notice, in a sharp point eight or ten inches long.

Then at the end of the mouth there are four lance-like teeth projecting forward and

outward. The object of these is to cut wider the breach his ram makes in the quivering

flesh of a mosasaur, so he can force his head into the bleeding flesh to the eye rims. But

his most terrible weapons are his pectoral fins. See, they are four feet long, serrated on

the cutting or outer edge, enameled, and as sharp as a knife. They can be locked, and

stand out straight from the body. A sudden swing would, if he was close to a mosasaur, cut

a gash several feet long in its vitals. See these fins span over eight feet. I pity the

fish or reptile that comes his way." "Hunting Dinosaurs in the Badlands of the Red Deer River, Alberta, Canada" (1917, p. 167-168). |

--------------------------0-------------------------------

|

LEFT: The right hind limb of a large Protostega gigas turtle (KUVP 1201) in the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History. It was collected by Charles Sternberg in 1900 west of Russell Springs in Logan County. This specimen was one of the first examples of the rear limb of this giant turtle ever found, and was the subject of a paper by S. W. Williston in 1902. See a colorized version of his Text-Figure 1 here. The femur (upper leg bone) is 360 cm (14 in) long. The entire limb would have been about 4 feet long. The specimen is still on exhibit at the University of Kansas. |

---------------------------0-------------------------------

From Von Huene, 1910 (see specimens above):

"In the fall of 1907 an expedition was carried out by the well-known American “fossil hunter” Mr. Charles Sternberg, in Logan County, Kansas, in order to collect specimens from the Upper Cretaceous formation (Niobrara Group) for the paleontological collection of the University of Tübingen. Among the abundant yield particular mention should be made of the largest known slab Uintacrinus and numerous very beautiful mosasaurs. The genus Tylosaurus is especially well represented. ..." |

--------------------------------0-------------------------------

--------------------------0-------------------------------

Katherine Rogers (1991, p. 129) noted that Charles H. Sternberg and his son, George F. Sternberg went to Washington D.C. in 1912, to visit Dr. Sternberg [ten years after his retirement from the Army and the post of Surgeon General of the Army]. Apparently the two brothers had not seen each other in many years. "Charles felt that at last he was in a position to let his brother know he'd made a success of life as a fossil hunter, and attributed no small part of that success to his brother's continued encouragement and assistance." "Charles gratefully recalled that it was his brother who had first alerted O. C. Marsh, Joseph Leidy and other paleontologists to the existence of Kansas' vast fossil beds, worthy of exploration"

--------------------------0-------------------------------

|

OBITUARY CHARLES H. STERNBERG.

Charles H. Sternberg, a ‘veteran and picturesque collector of fossils, died on

June 21st, 1948, at the advanced age of 98 years. With him one of the few remaining links

with the heroic age of Vertebrate Paleontology in America was severed; but the

tangible results of his years of service may be seen in the exhibition halls and study

collections of many of the famous museums of the United States and Canada as well as of

Europe.

Charles H. Sternberg was born at Middleburg, New York, on June 15th, 1850. Even as

a youngster he was interested in fossils which he cut from the limestone ledge near his

home. In 1867 he moved to Central Kansas, near old Fort Harker which was the end of steel

of the Union Pacific railway. Soon after he discovered many fine leaf impressions in the

Dakota sandstones and made a number of collections of these fossil plants at various

times. He had many experiences with the Indians and the pioneers of the West for he was

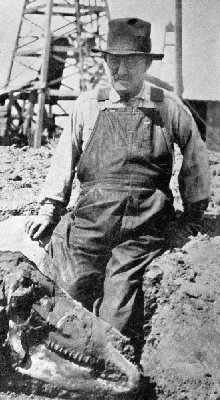

usually at the outposts of civilization. LEFT: Charles H. Sternberg collecting a horse skull in the McKittrick oil field in 1926-27 (Larger photo by C.H. Sternberg here). Adapted from Rogers 1991(*). |

|

In 1912 he moved to Canada to take charge of collecting and

preparing vertebrate fossils for the Geological Survey, and during the next four years he

and his three Sons built up a large collection of Upper Cretaceous dinosaurs for the

Museum at Ottawa. In 1916 he resigned his position and returned to Kansas to continue

independent collecting. In 1918 he moved to California where he remained until the death

of his wife in December 1938.

|

| * For more information on the Sternberg Family: Rogers, K. 1991. A dinosaur dynasty: The Sternberg fossil hunters. Mountain Press Publishing Company, 288 pages. |

A Partial List of Publications by Charles H. Sternberg (including links to ePapers on Oceans of Kansas):

Sternberg, C.H. 1881. The Quaternary of Washington Territory. Kansas City Review of Science and Industry 4(9):540-542.

Sternberg,

C.H. 1881. The Pliocene Beds of Southern Oregon. Kansas City Review of Science

and Industry 4(10):600-601.

Sternberg, C.H. 1881. The Quaternary of Washington Territory. Kansas City Review of Science and Industry 4(10):601-602.

Sternberg, C.H. 1881. The Dakota Group. Kansas City Review of Science and Industry 4(11):675-677.

Sternberg, C.H. 1881. The Judith River Group. Kansas City Review of Science and Industry 4(12):730-733.

Sternberg, C.H. 1881. The Niobrara Group. City Review of Science and Industry 5(1):1-4.

Sternberg, C.H.

1881. The fossil flora of the Cretaceous Dakota Group. Kansas City Review of Science and Industry 5(4):243-244.

Sternberg, C.H. 1882. The Loup Fork Group of Kansas. Kansas City Review of Science and Industry. 6(4):205-208.

Sternberg,

C.H. 1884. The fossil fields of southern Oregon. Kansas City Review of Science

and Industry 7(10):596-599.

Sternberg, C.H. 1884. The flora of the Dakota Group. Kansas City Review of Science and Industry 8(1):9-12.

Sternberg, C.H. 1884. Directions for collecting vertebrate fossils. Kansas City Review of Science and Industry 8(4):219-221.

Sternberg, C.H. 1884. Practical studies in Geology. Kansas City Review of Science and Industry 8(1):481-485.

Sternberg, C.H. 1898. Cretaceous leaf nodules. Popular Science News 32:25 (February).

Sternberg, C.H. 1898. Pliocene Man. Popular Science News 32:82 (April).

Sternberg, C.H. 1898. A mine of mammoths. Popular Science News 32:169 (August)... also includes photo of mounted Teleoceras.

Sternberg, C.H. 1898. Ancient monsters of Kansas. Popular Science News 32:268 (December).

Sternberg, C.H. 1899. The first great roof. Popular Science News 33:126-127, 1 fig. (June).

Sternberg, C.H. 1899. A Kansas mosasaur. Popular Science News 33:259-260.

Sternberg, C.H. 1900. Fossil collector's experiences. Popular Science News 34:34 (February).

Sternberg, C.H. 1900. The sharks of Kansas. Popular Science News 34:38 (February).

Sternberg, C.H. 1901. A Cretaceous monster fish. Popular Science News 35:29-30 (February).

Sternberg, C.H. 1902. The Permian of Texas. Popular Science News 36:106-107 (May).

Sternberg, C.H. 1902. A plesiosaur of the

Cretaceous ocean. Popular Science News 36:248 (November).

Sternberg, C.H. 1903. Experiences with early man in America. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 18:89-93.

Sternberg, C.H. 1903. The Permian Life of Texas. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 18:94-98.

Sternberg, C.H. 1905. Protostega gigas and other Cretaceous reptiles and fishes from the Kansas chalk. Kansas Academy Science, Transactions 19:123-128.

Sternberg, C.H. 1906. Some animals discovered in the fossil beds of Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 20:122-124.

Sternberg, C.H. 1907. My expedition to the Kansas Chalk for 1907. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 21:111-114.

Sternberg, C.H. 1907. Portheus molossus Cope, and other fishes from the Kansas chalk. Science 25:295.

Sternberg, C.H. 1909. Expedition to the Laramie Beds of Converse County, Wyoming. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 22:113-116.

Sternberg, C.H. 1909. An armored dinosaur from the Kansas chalk. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 22: 257-258.

Sternberg, C.H. 1909. The life of a fossil hunter. Henry Holt and Company, 286 p. (reprinted by the Indiana University Press, 1990).

Sternberg, C.H. 1911. In the Niobrara and Laramie Cretaceous. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions23:70-74.

Sternberg, C.H. 1913. Expeditions to the Miocene of Wyoming and the chalk beds of Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 25:45-49. (Papers - Forty-fifth annual meeting, 1912) State Printing Office, Topeka.

Sternberg, C.H. 1914. Notes on the fossil vertebrates collected on the Cope expedition to the Judith River and Cow Island beds, Montana. Science (New Series) 40(1021):134-135.

Sternberg, C.H. 1915. Evidence proving that the Belly River beds of Alberta are equivalent with the Judith River beds of Montana. Science (New Series) 42(1073):131-133.

Sternberg, C.H. 1918. Five years explorations in the fossil beds of Alberta. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 28:205-211.

Sternberg, C.H. 1918. Sternberg's expedition to the Red Deer River, Alberta, 1917. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 29:88-91.

Sternberg, C.H. 1917. Hunting Dinosaurs in the Badlands of the Red Deer River, Alberta, Canada. Published by the author, San Diego, Calif., 261 pp.

Sternberg, C.H. 1922. Explorations of the Permian of Texas and the chalk of Kansas, 1918. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 30(1):119-120. (Papers - Fifty-first annual meeting, 1919).

Sternberg, C.H. 1922. Field work in Kansas and Texas. [1919] Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 30(2):339-348. (Papers - Fifty-second annual meeting, 1920).

Sternberg, C.H. 1929. Fossil monsters I have hunted. Popular Science Monthly 115:56, 57, 139, 140 (December).