|

Kansas Academy of Science.

119 Explorations of the Permian of Texas and the Chalk

of

Kansas, 1918.

CHARLES H. STERNBERG.

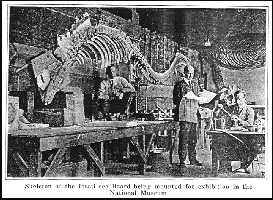

The splendid skeleton of Dimetrodon gigas I

collected in 1917 and sold to the United States National Museum has been mounted at last,

and is one of the world's famous specimens. I do not know of a more perfect single

individual. It came from the famous Craddock quarry discovered by the late Doctor

Williston's assistant, Mr. Miller. Through the kindness of Mr. Craddock, the owner of the

quarry, I not only collected there in 1917, but last year. Owing to the fact that the

quarry is now covered with about twenty feet of earth and clay of the toughest character

the work was very difficult and I was obliged to employ a man with a heavy team of horses,

with plow and scraper. I succeeded in securing many more or less perfect skeletons of

several species. Unfortunately, none were as perfect and capable of making into a fine

open mount as the National Museum specimen. This quarry is in the face of a hill. As I

have gone deeper and deeper into the hill the manner in which the animals were stranded

here becomes more and more apparent. On the very bottom of the quarry are innumerable

bones of very small animals, Seymoriana and other batracians, etc. They are usually

scattered and are free from matrix, consequently they are among the rarest of Permian

vertebrates that have not been injured by the encrusting silica that covers all the other

bones at higher levels, and which is so difficult. to remove. The National Museum specimen

came from near this level. Above are about four or, five feet in the heavy, fine-jointed

red clay. Though water has filtered and coated all the bones with silica, I found several

more or less perfect skeletons. Often the entire column, except the tail, with enormous

spines were present; sometimes the arches and limbs, as in the best specimen we found,

discovered by my son, George F. The longest spine of this individual was four feet.

Most of the column and tail were present. The skull was disarticulated. The arches seemed

present. Many of the spines, however, were twisted and interwoven, all the bones covered

with a thin coating of silica. As I understood Doctor Gilmore, it took two preparators a

year to prepare and mount the National Museum specimen. You will realize something of the

labor it will take to prepare this one. This, with my whole collection from the Craddock

quarry, I sold to the American Museum.

From Seymour, Tex., my boys, George and Levi, drove my

car to the Rock creek Horse quarry, near Tulia, Tex.. but the formidable mass of sand that

lay above it induced them to turn their Ford truck northward, and I joined them in the

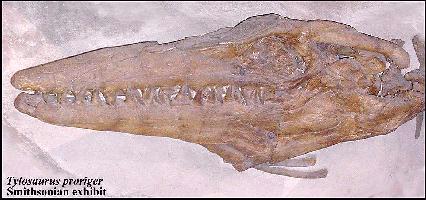

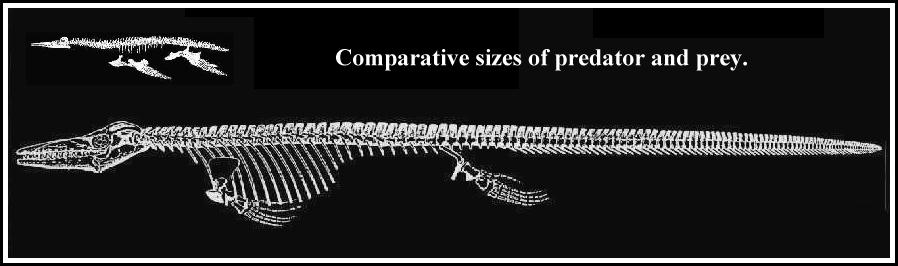

Kansas chalk in Logon county, on Butte creek. I was so fortunate as to find a fine

tylosaur skeleton the second day in the field. There were twenty-one feet of the skeleton

present in fine chalk. The complete skull was crushed laterally, nearly the complete front

arches and limbs were present, as was also the pelvic bones and both femora. All the

vertebræ to well into the caudal region beyond the lateral spines were continuous, with

the ribs in the dorsal region. Between the ribs was a large part of

a huge plesiosaur with many half-digested bones, including the large humeri, part of the |

120

Kansas Academy of Science.

coracoscapula, phalanges, vertebræ, and, strangest of

all, the stomach stones, showing that this huge tylosaur, that was about twenty-nine feet

long, had swallowed this plesiosaur in large enough chunks to include the stomach. How

powerful the gastric juice that could dissolve these big bones! This specimen I sent to

the United States National Museum. A little Clidastes

skeleton found by my son Levi proves not only to be new, but possessed of remarkable

characters not yet described. I will only in a general way give you an idea of this little

sea lizard. It is 8 ½ feet long, skull 14 inches long. Levi in preparing the skeleton

restored the maxilla, jugals, nasals and prosquamosals, with the ends of some of the

teeth; also four of the cervical and one dorsal vertebra. These had been destroyed by

incrusting gypsum. The bifrucated coracoids, 2 inches wide, are large compared to the

scapulæ, which are only 1 ¼ inches wide. The most remarkable thing about this mosasaur

is the fact that the humeri and femora have distinct, round heads, similar to those of

mammals. Further, all the Clidastes humeri I know are broad, square bones, nearly

as broad as they are long. In this specimen the humerus is 2 ¼ inches, while it is only 1

¼ inches wide in the widest part; the same with the femur. The front paddle is 7 inches

long to ends of first row of phalanges; width only 2 ½ inches. The column is continuous

to the pygals, where they are scattered. The pelvic arches and paddles are only partially

preserved. The caudals are beautifully preserved, with a high fin in the last half of the

column; the chevron well preserved, with all of them anchylosed to the centra of the

vertebræ. The only genus among the mosasaurs where this is the case. They usually are

distinct, the proximal heads fitted snugly into little basins hewn out., as it were, from

the centra of the vertebræ. I own this new Clidastes. [now Eonatator (Halisaurus) sternbergi, described by Carl

Wiman, 1920; revised to Halisaurus by Russell (1967) and most recently to Eonatator

(novem gen.) by Bardet, et al., 2005).

We secured two specimens of Platecarpus

coryphæus of exactly the same size. One found by Levi Sternberg has much

of the head, the column, and ribs to the pygals. The second, found by George F. Sternberg,

has a very complete tail to the very end, and the pelvic arch and one paddle; other

specimens furnished the rest of the paddles. We have mounted this as a slab specimen, and

makes a skeleton 17 feet long-very impressive, indeed. George F. Sternberg found also a

very fine skull and most of the skeleton of a small Pteranodon.

The skull is only 27 inches long; missing, only the crest and front of the mandibles. Both

coracoscapula are present, with one humerus, radius, ulna, carpal joint., and most of one

elongated finger. Both hind limbs and several vertebræ and ribs. This, when prepared,

will be one of the few fine skulls of these flying reptiles. We secured also a very fine Portheus, complete, nearly, except the ends of the ribs, the

dorsal and caudal fins, and 18 caudal vertebræ. These we have restored, and we have a

fish 13 feet long, with spread of tail fins of 35 inches. These are the chief discoveries

of my last season's labor in the Permian of Texas and the chalk of Kansas.

|