Cretoxyrhina mantelli - The Ginsu Shark*

and

Squalicorax falcatus - The Crow Shark**

Large Sharks in the Western Interior Sea

Copyright © 1999-2013 by Mike Everhart - Last Modified: 10/22/2013

|

Cretoxyrhina mantelli - The Ginsu Shark*and Squalicorax falcatus - The Crow Shark** Large Sharks in the Western Interior SeaCopyright © 1999-2013 by Mike Everhart - Last Modified: 10/22/2013

LEFT: Copyright © Doug Henderson; used with permission of Doug Henderson |

May 12, 2003 - Translated into French |

“The Portheus, now swimming for life, was the foci of the sharks that were coming to the attack from all directions. One would dive under the fish, and receive, for his pains, a stroke from his powerful tail that would put him out of commission; another would receive a thrust from the sword-like ray of the front fin. Undaunted, others hurried up like a pack of wolves on a wounded deer. Though many were wounded in the fray, our hero fish at last succumbed to numbers, who gashed his body with their lance-like teeth, and the water was tinged with his life blood, until, weakened and overpowered, he gradually ceased struggling. The sharks gathered to the feast. One, however, was so badly wounded by the Portheus, that he went to the oozy bottom with him. I have preserved in the Museum of the University of Kansas a shark twenty-five feet long, and mingled with his remains were the bones of a Portheus, the evident result of such a combat … “(KUVP-247) Excerpted from Charles H. Sternberg's "Hunting Dinosaurs on the Red Deer River, Alberta, Canada" (1917, p. 162). |

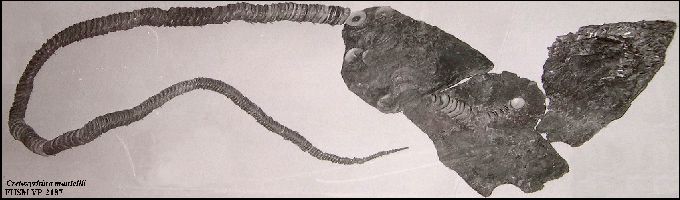

While the passage from C.H. Sternberg's book is fiction, it is based on the discovery of the remains (KUVP 247) of a large Cretoxyrhina mantelli (Ginsu shark) that also contains the scattered bones of a large Xiphactinus as its last meal. The specimen is on exhibit in the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History in Lawrence, Kansas. (Note that "Portheus" as used by Sternberg is a junior synonym for Xiphactinus audax)

Sharks were a very important part of the ecosystem of the Western Interior Sea just as they are in the oceans of today. They 'recycled' (scavenged) dead animals and were probably active predators as well. There were fewer varieties of sharks in the mid-ocean area that covered Kansas than along the eastern and western shores and the Gulf Coast. The most common species were Cretoxyrhina mantelli and Squalicorax falcatus / S. kaupi. Their shed teeth are frequently found as fossils in the Smoky Hill Chalk Member of the Niobrara Formation. Found less often are their vertebrae and preserved cartilage from the jaws and cranium, and from their fins. Other species included Cretalamna (Otodus) and Scapanorhynchus. Another group of sharks (Pavement-Toothed or Ptychodontid) lived on the bottom and feed on hard shelled invertebrates. Click here for another Ptychodus page.

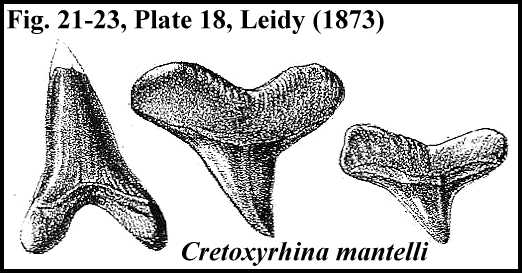

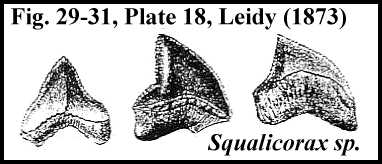

Dr. George M. Sternberg, along with John LeConte and Professor B. F. Mudge, were among the the first to collect sharks teeth from the Smoky Hill Chalk in the late 1860s. While the contributions of Prof. Mudge were acknowledged by Cope (1874), Sternberg was credited by Leidy (1873), including several specimens that he illustrated. The figures published by Leidy are shown below:

|

Cretoxyrhina mantelli teeth collected by George M. Sternberg "from the Cretaceous formation of Kansas." |

|

A small collection of Squalicorax teeth: left tooth - S. falcatus; right two teeth, either S. kaupi or possibly S. pristodontus. (collected by George M. Sternberg "from the Cretaceous of Kansas") |

* AUTHORS NOTE: Over the past several years, we have found a number of instances where the fossilized ‘parts and pieces’ of mosasaurs are all that remained of some sort of feeding activity. In some cases, these fossils have been partially digested by something large enough to swallow a large piece of a mosasaur. In others, there are embedded pieces of teeth from the large lamnid shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli. In one well documented specimen (FHSM VP-13283), there were embedded Cretoxyrhina teeth, two vertebrae that had been bitten completely through, and the evidence of partial digestion (Shimada, 1997; Everhart, 1999). We were left with the conclusion that it was this large and apparently very powerful shark that was feeding on mosasaurs. Since the shark had no common name in the literature, and since it fed by ‘slicing’ up its victim into bite-size pieces, we decided that the title “Ginsu Shark”, was an appropriate, descriptive (and somewhat humorous) name for this awesome creature. Ginsu, of course, refers to a brand of knives that were advertized on television years ago for their sharp blades and ability to "slice and dice."

Cretoxyrhina mantelli was probably the largest of the sharks in the Western Interior Sea during the late Cretaceous. It's maximum size is estimated at 6.5 to 7 meters (about 22 feet). It's razor sharp teeth are large, triangular and smooth edged, in contrast to the serrated edges found on the more common, but much smaller, shark in the seaway, Squalicorax falcatus (and later, S. kaupi and S. pristodontus). Most of the teeth that are found were those that were periodically shed by the shark, or those lost during feeding. Cretoxyrhina mantelli became extinct world-wide during early Campanian time (about 82 million years ago). (For more information about Cretaceous sharks, click here). --------

You can now download a copy of this early article on Kansas Sharks by Williston - Provided by the Kansas Geological Survey.

Williston, S. W. 1900. Cretaceous fishes: Selachians and Pycnodonts. University Geological Survey Kansas VI pp. 237-256, with pls.

|

LEFT: The well preserved remains of a large (5 meter - 16 ft.) Cretoxyrhina mantelli (FHSM VP-2187) is on

exhibit in the Sternberg Museum of Natural History in Hays,

Kansas. Although sharks have no bones, enough calcium apparently accumulated in the

cartilage of the vertebrae, jaws and cranium that these structures can occasionally

be preserved as fossils. The specimen was collected by G.F. Sternberg in 1965 from

the lower Smoky Hill Chalk of Ellis, Kansas. RIGHT: Close-up of the preserved cranium, jaws and teeth. |

|

Shown below are five pictures of the head and teeth of this specimen. The largest teeth are about 52 mm (2 inches) in height. The sixth picture is of another Cretoxyrhina mantelli specimen at the Sternberg (FHSM VP-323).

|

ABOVE: This drawing (adapted from Shimada, 1994) shows the arrangement of teeth in the upper and lower jaws of Cretoxyrhina mantelli. (Click here for another view) The front of the jaw is to the left. This shark had a total of about 80 teeth at the gum line. Each of these teeth had as many as 7 replacement teeth in various stages of growth on the inside of the jaws.

The pictures shown below are of sharks teeth found in the Smoky Hill Chalk Member of the Niobrara Chalk Formation of western Kansas. All of the teeth, except those in the next to the last picture, are of late Coniacian age (about 87-86 mya). (Adapted from Shimada, 1994)

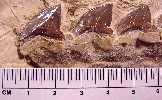

| Part of my collection of Cretoxyrhina mantelli teeth from

the lower Smoky Hill Chalk Formation (late Cretaceous). Shark teeth are shed frequently

and replaced throughout the life of the shark. Labial view of a Cretoxyrhina mantelli tooth. (Scale in mm)

|

|

|

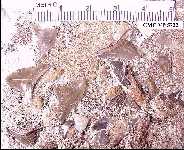

LEFT: This group of about sixty Cretoxyrhina mantelli

teeth (and two vertebrae) of the more that 110 teeth that were originally from a single shark (FHSM

VP-14004) that I collected in 1992 (EPC 1992-08). The photo

shows the large variety of shapes and sizes of teeth that were a part of the dentition of

this species. Unfortunately, these teeth represent the 'left-over' remains of a nearly

complete specimen that was poached (and essentially destroyed) from private property. Ten Squalicorax falcatus teeth associated with the remains are curated as FHSM VP-14005) Scale is in centimeters. More recent photos of the VP-14004 specimen here and here. See Bourdon and Everhart (2011) for additional photos and analysis of this specimen.

Bourdon,

J. and Everhart, M.J. 2011. Analysis of an associated Cretoxyrhina mantelli dentition

from the Late Cretaceous (Smoky Hill Chalk, Late Coniacian) of western Kansas. Kansas

|

|

This is a slightly 'larger than life' photograph of the largest Cretoxyrhina mantelli tooth in our collection. About 52mm in height, it is nearly as large as the largest known teeth of this species from the Niobrara Chalk Formation. A larger tooth is here (Fick Fossil and History Museum). |

| These two teeth come from the upper Smoky Hill chalk, just below the contact with the Pierre Shale (lower Campanian). These teeth are about 82 million years old. Cretoxyrhina mantelli is unknown from the shale. |  |

|

LEFT: Xiphactinus as the last

meal of a large shark - KUVP 247 in the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History. George F. Sternberg discovered the remains of a large Cretoxyrhina mantelli (Ginsu shark) in Trego County that contained the scattered bones of a large Xiphactinus as its last meal. The specimen was sold to the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History in Lawrence, Kansas where it is currently on display.. Larger view of the Cretoxyrhina jaws and teeth. Larger view of the exhibit Larger view of the Xiphactinus remains found inside the shark |

|

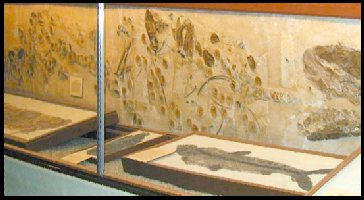

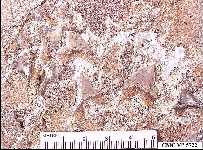

LEFT: Calcified vertebral centra from a large Cretoxyrhina

mantelli (FHSM VP-2184). The specimen included over 100

centra, but only a few teeth.

RIGHT: Overview of the entire FHSM VP-2184 specimen. |

|

SQUALICORAX - Extinct Crow Shark**

For more information about these sharks - GO HERE

Benjamin F. Mudge was one of the first to collect the associated remains of this shark in Kansas. In his Report to the Board of Agriculture, Mudge (1878) wrote, "quite recently I had the good fortune to find the teeth, cartilaginous jaw and vertebrae of a shark -- Galeocerdo falcatus -- three portions, which, I think, have never hitherto been found together. The flat, porous vertebrae had occasionally been collected, but we had been unable to give them their generic name. The teeth are frequently procured." Unfortunately, it is unknown what happened to this specimen when the collections of the Kansas Academy of Science were moved, and then broken up.

NOTE:While I can honestly take credit for being the first to use the term "Ginsu shark" as a common (but appropriate) name for Cretoxyrhina mantelli (above), the origin of the term "Crow Shark is a bit more mysterious. I don't know when it was first used or who used it, but I suspect it goes back to the meaning of the Greek word "Corax." The genus name, "Squalicorax" was originally just "Corax." (e.g. Corax falcatus Agassiz 1843). Corax is a name found in Greek mythology, but also is the species name for the common raven (a bird) of Europe (Corvus corax). (From Wikipedia, in regard to Corvus corax, "the specific epithet, corax/???a?, is the Greek word for "raven" or "crow". Whitley (1939) changed the genus name to Squalicorax. At some point, Squalicorax was given the common name, Crow shark.

|

In June, 1992, I came across several flat, disk shaped vertebrae eroding from the side of a gully. When I uncovered more of them, they led me to the complete skull of a small Squalicorax falcatus shark. |

|

There were several teeth visible when I reached the end of the specimen. I stopped digging downward at this point and began to explore for the 'edges' of the remains. The flattened head of the shark was about 10 inches wide and a foot or so in length. |

|

Once I had the specimen back in the lab, I was able to carefully clean away the chalk. Underneath I found what appeared to be preserved skin (denticles) covering the cartilage braincase and jaws of the shark. In this picture, the shark is laying upside down with the teeth of the upper jaw nearest the outer edge and the teeth of the lower jaw jumbled inside. In 1999, this specimen was donated to the Cincinnati Museum Center (CMC VP 5722) (See Shimada and Cicimurri (2005) for a detailed description) |

In February, 2003, I had the opportunity to visit the Cincinnati Museum Center and photograph the remains again. The specimen preserves the teeth roughly in the jaws... and the dermal denticles (scales, HERE and HERE) in the shark skin preserve the rough outline of the head. The preserved vertebrae (calcified cartilage) is shown HERE.

|

|

|

|

|

LEFT: This scan shows a collection of shed Squalicorax falcatus teeth from the lower 1/3 of the Smoky Hill chalk (late Coniacian). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The above teeth and preserved cartilage are from a well preserved Squalicorax kaupi (FHSM VP-2213) in the Sternberg Museum. The first picture shows the lower jaws with several teeth still in place. The 2nd, 3rd and 4th pictures show teeth that are still in their natural position on the jaw. The 5th picture shows two teeth in place on the edge of the jaw with two replacement teeth waiting to move up from the inside of the jaw. The last picture shows the other side of the teeth in picture #5.

|

The picture at left is a juvenile hadrosaur limb bone from the

Selma group of the Mooreville formation (late Cretaceous), Dallas County, Alabama with Squalicorax

bite marks. (From a specimen in the Field Museum,

Chicago, IL.) Below are mosasaur tail vertebrae with Squalicorax bite marks.

The second picture shows a close-up of the dorsal process of the 3rd vertebra, with

deep bite marks. The third picture is a shark-bitten rib bone from another mosasaur |

Known as 'Crow Sharks' (see note above), members of this species probably grew no larger than 3 meters in length during the deposition of the Smoky Hill chalk (See Shimada and Cicimurri (2005) for a detailed description). There is ample evidence that the species was an active scavenger. The marks made by it's serrated teeth are commonly found on the remains of many species, including some dinosaur bones from the Cretaceous Gulf Coast.

Kansas Sharks - A photographic essay from the Lower Permian to the Upper Cretaceous.

A REALLY Big Ginsu Shark - Discovered in 2002 in western Kansas

Cretoxyrhina mantelli - The Ginsu Shark - The biggest shark in the Western Interior Sea

Sharks feeding on mosasaurs - Parts is parts and pieces are pieces.

More on sharks?? See Jim Bourdon's The Life and Times of Long Dead Sharks - "Elasmo.com"

A Moment in Time - Shark Predation on Mosasaurs ---- Even mosasaurs were shark food...

One Day in the Western Interior Sea..... Watch out! Life could be very short for the unwary.

References on Cretaceous Sharks (Also see my Cretaceous fish reference page here):

Agassiz, L., 1874. Three different modes of teething among selachians. The American Naturalist, 8(3):129-135.

Bourdon,

J. and Everhart, M.J. 2011. Analysis of an associated Cretoxyrhina mantelli dentition

from the Late Cretaceous (Smoky Hill Chalk, Late Coniacian) of western

Druckenmiller, P. S., A. J. Daun, J. L. Skulan and J. C. Pladziewicz, 1993. Stomach contents in the upper Cretaceous shark Squalicorax falcatus. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology (abstract) 13(suppl. to 3):33A.

Everhart, M. J., 1999. Evidence of feeding on mosasaurs by the late Cretaceous lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli. (abstract) Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 17(suppl. to 3):43A-44A.

Everhart, M. J. 2004. Late Cretaceous interaction between predators and prey.

Evidence of feeding by two species of shark on a mosasaur. PalArch, vertebrate

palaeontology series 1(1):1-7.

Everhart, M. J. 2004. First record of the hybodont shark genus, “Polyacrodus”

sp., (Chondrichthyes; Polyacrodontidae) from the Kiowa Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of

McPherson County, Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 107(1/2): 39-43.

Everhart, M. J. 2005. Bite marks on an elasmosaur (Sauropterygia; Plesiosauria) paddle

from the Niobrara Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) as probable evidence of feeding by the

lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli. PalArch, Vertebrate paleontology 2(2):

14-24.

Everhart, M. J. 2005. Oceans of Kansas - A Natural History of the Western Interior Sea.

Indiana University Press, 322 pp.

Everhart, M. J. and Caggiano, T. 2004. An associated dentition and calcified vertebral

centra of the Late Cretaceous elasmobranch, Ptychodus anonymus Williston 1900.

Paludicola 4(4), p. 125-136.

Everhart, M. J., T. Caggiano and K. Shimada, 2003. Note on the occurrence of five species

of ptychodontid sharks from a single locality in the Smoky Hill Chalk (Late Cretaceous) of

western Kansas. Kansas Academy Science Abstracts, 22:29.

Everhart, M. J. and M. K. Darnell. 2004. Occurrence of Ptychodus mammillaris

(Elasmobranchii) in the Fairport Chalk Member of the Carlile Shale (Upper Cretaceous) of

Ellis County, Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 107(3-4):126-130.

Everhart, M. J. and P. A. Everhart. 1998. New data regarding the feeding habits

of the extinct lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli, from the Smoky Hill Chalk

(upper Cretaceous) of western Kansas. (abstract) Kansas Acad. Sci. Trans. 17:33.

Everhart, M. J., P. A. Everhart and K. Shimada. 1995. New specimen of shark bitten

mosasaur vertebrae from the Smoky Hill Chalk (upper Cretaceous) in western Kansas.

(abstract) Kansas Acad. Sci. Trans. 14:19.

Mudge, B. F. 1878. Geology of Kansas. Pages 60-63 in First Biennial Report of the Kansas State Board of Agriculture. Topeka.

Schwimmer, D. R., J. D. Stewart, and G. D. Williams, 1997. Scavenging by sharks of the genus Squalicorax in the late Cretaceous of North America. PALAIOS, 12:71-83.

Shimada,

K., 1996. Selachians from the Fort Hays Limestone Member of the Niobrara Chalk (Upper

Cretaceous), Ellis County, Kansas. Kansas Acad. Sci. Trans. 99(1-2):1-15.

Shimada, K., 1997. Dentition of the late Cretaceous lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina

mantelli, from the Niobrara Chalk of Kansas. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology

17(2):269-279.

Shimada, K., 1997. Shark-tooth-bearing coprolite from the Carlile Shale (upper

Cretaceous), Ellis County, Kansas. Kansas Acad. Sci. Trans. 100(3-4):133-138.

Shimada, K., 1997. Stratigraphic record of the late Cretaceous lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina

mantelli (Agassiz), in Kansas. Kansas Acad. Sci. Trans. 100(3-4):139-149.

Shimada, K., 1997. Gigantic lamnoid shark vertebra from the lower Cretaceous Kiowa Shale

of Kansas. Journ. Paleon. 71(3):522-524.

Shimada, K., 1997. Paleoecological relationships of the late Cretaceous

lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli (Agassiz). Journ. Paleon. 71(5):926-933.

Shimada, K., 1997. Periodic marker bands in vertebral centra of the late Cretaceous

lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli. Copeia 1:233-235.

Shimada, K., 1999. Dentitions of lamniform sharks: Homology, phylogeny and paleontology.

Doctoral dissertation, University of Illinois at Chicago, 486 pp.

Shimada, K. 2008. Ontogenetic parameters and life history strategies of the Late Cretaceous lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli, based on vertebral growth increments. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 28(1):21-33.

Shimada, K. and Cicimurri, D.J. 2005. Skeletal anatomy of the Late Cretaceous shark, Squalicorax (Neoselachii: Anacoracidae). Paläontologische Zeitschrift 79(2): 241-261.

Whitley, G. P. 1939. Taxonomic notes on sharks and rays. Australian Journal of Zoology 9(3):227–262.

Williston, S. W. 1900. Cretaceous fishes [of Kansas]. Selachians and Pycnodonts. University Geological Survey Kansas VI pp. 237-256, with pls.

Credits: The painting of Cretoxyrhina mantelli is copyright Doug Henderson; used with permission. The Cretoxyrhina mantelli teeth drawing was adapted from the unpublished Master's thesis, "Paleobiology of the Late Cretaceous Shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli" by Kenshu Shimada, Fort Hays State University, 1994.