| 273 An Extinct

Sea Lizard from Western Kansas

By Charles W. Gilmore

T HE chalk deposits of western Kansas have long been

famous on account of the great number and the fine state of preservation of the fossil

remains found in them. For more than fifty years collectors of fossils have searched the

chalk exposures for their hidden treasures. Remains of fish, large and small, turtles,

toothed birds, lizards, both swimming and flying, and an occasional

dinosaurian reptile have been the rewards of these indefatigable hunters.

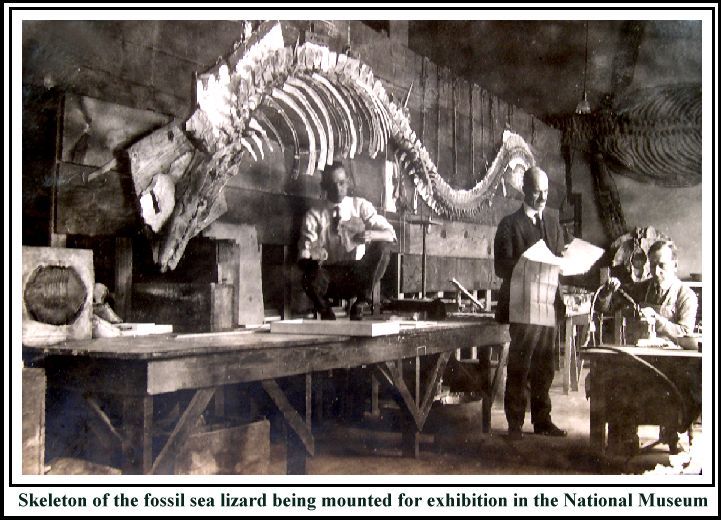

The United States National Museum numbers among its rarest

treasures fossil remains of all of these several kinds of animals, but quite recently

there has been added to the exhibition series the very fine specimen of a swimming or sea

lizard shown in the accompanying illustration. This animal goes under the name of Tylosaurus proriger, and belongs to a group of

extinct reptiles commonly called Mosasaurs. The Mosasaurs were water living reptiles, with

long slender bodies having the limbs modified into short swimming paddles, and a long

powerful compressed tail with which they propelled themselves through the water. This

specimen, after many weeks of the most painstaking care and skilful work, was cleaned from

the investing chalk, the broken parts repaired and the missing bones restored, until

finally the skeleton was articulated in the pose shown. It forms a wall panel, the

skeleton being in half relief, the dark bone of the specimen standing out in bold contrast

against the light yellowish color of the background, which has been made in imitation of

the yellow chalk in which the specimen was originally found. The pose adopted for the

skeleton was largely determined by the curved articulated sections of the backbone as

found in the ground.

This specimen was collected for the National Museum by the

veteran collector of fossils, Mr. Charles H. Sternberg, on Butte

Creek, Logan County, Kansas, in 1917. Mr. Sternberg and his three sons, all of whom

have been raised as fossil hunters, have collected hundreds of these ancient monsters and

the results of their discoveries are to be found in all of the principal museums of the

world, the present specimen being still another contribution to the science to which they

have given so much.

The Tylosaurus specimen, as now exhibited, measures

about twenty-five feet in length, with a head that is three and one-half feet long. The

largest of the Mosasaurs, however, sometimes attained a length of forty feet, and such an

animal would have a head fully five feet long. Some of the small adult species were

scarcely more than eight feet in length.

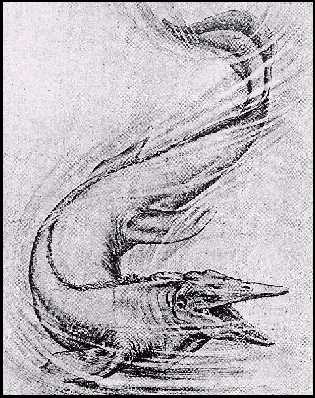

The seas that rolled over Kansas in Cretaceous times

contained thousands of these animals, and in the chalk bluffs of that region their remains

are in such a perfect state of preservation that we are not only acquainted with their

skeletal structure but with their external appearance as well. Impressions made by the

body in these soft sediments before decomposition had set in have been found, showing that

in life they were covered with small overlapping scales.

In fact, small areas of skin impressions were found with the Tylosaurus specimen

here discussed. The most unusual discovery relating to the appearance in life of an animal

long extinct, was the detection of color markings by Doctor Williston, who

(Continued on page 280) |

280

An Extinct Sea Lizard from Western Kansas

(Continued from page 273)

observed on one specimen carbonized pigment, which showed that the sides of the

body were marked by narrow, diagonally placed parallel bars.

One of the unique features of Tylosaurus, and for

that matter of all mosasaurs, is an articular joint in about the middle of each lower jaw,

which permits considerable movement between the front and back parts, both up and down and

sideways, though chiefly in the latter direction. This feature in conjunction with their

very loose attachment to one another at the forward ends allowed the jaws to expand and

thus enabled them to swallow large objects, for it is certain that not all of the animals

which the Tylosaurus devoured were small, for since their teeth were not adapted

for the rending of bodies they must have been swallowed whole.

While most of the Mosasaurs were predatory animals having

the jaws provided with numerous sharply pointed teeth

that were well adapted for catching fish - for it is thought fish formed their principal

article of diet, since fish bones and scales have been found among the fossilized stomach

contents - there was another kind of Mosasaur, Globidens

alabamaensis [sic], that formerly lived in North America and enjoyed quite a

different kind of food as shown by the very peculiar shape of its teeth. Reference is made

to a specimen in the National Museum found some few years ago in the northern part of the

State of Alabama which has nearly spherical teeth.

Mosasaur specimens have not only been found in many parts of

the United States, but in South America, Belgium, Holland, Russia, France and New Zealand,

but nowhere are they more abundant or are their remains found in a more perfect state of

preservation than in the chalk deposits of western Kansas.

|