| 70

Kansas Academy of Science. IN THE NIOBRARA AND LARAMIE

CRETACEOUS.

By CHARLES H. STERNBERG, Lawrence.

THE early part of the season was spent in the Kansas chalk. As has been

the case during many of the last thirty-five years, since I first began collecting in this

formation, I have been quite successful. My three sons, George, Charles and Levi, were

with me, while the monotony of camp life was broken by the presence of my son George's

wife and baby son. We made our first camp at Mrs.

Livingston's ranch, on Hackberry creek, south of Quinter, Kan., in Gove county, near the

eastern line. And we are under many obligations to Mrs. Livingston and her two sons

for shelter for our team, as well as hay; otherwise our horses might have suffered from

the inclemency of the weather .

While here I experienced for the first time a very

peculiar electric storm. About the 10th of May a violent wind and dust storm came up from

the northeast about sundown, and gravel, sand and earth were hurled through the air with

great force. I faced it for a hundred yards to get my son Levi, who was at the barn. My

face was beaten with sand and gravel, and I could hardly walk, owing to the fury of the

gale. However, I got to the barn, and, taking my son's hand, we started to return. It was

so dark that we could not see an inch ahead. What was my surprise to see the telephone

line that was suspended over my tent dotted with points from which light radiated in all

directions, and as far as I could see the line it was swinging, with myriad little lamps,

back and forth with the wind. Looking around, I saw posts that supported a barbed-wire

fence sending out light in the same way, except of course, they were stationary. I found

after the storm that these centers of light were nails driven in the posts. So for the

first time in the history of western Kansas, as far as I have observed, we had a display

of St. Elmo's fire.

At our camp on Hackberry we discovered, among other

fine material, the largest example of a species of Inoceramus

I have ever seen preserved. It measured four feet in height and five feet in length.

At certain horizons in the Niobrara of Kansas acres of chalk are strewn with fragments of

these shells in endless profusion, owing to the fact that the chalk is disintegrated and

washed away by water or blown to the four points of the compass

Geological Papers.

71

by Kansas winds, No wonder the late Prof. E. D. Cope saw in imagination these

shells as the remains of a feast of Titans.

This great cretaceous shell will be mounted in

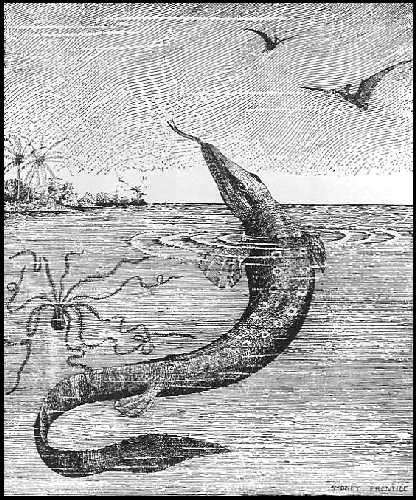

the American Museum, New York. We found in the same vicinity enough material of the

mosasaur Platecarpus coryphæus to enable us, with the

assistance of some exchanges we made with the University of Kansas, to make a complete

slab mount of this swimming lizard, once so abundant along the shores of the old

cretaceous ocean in western Kansas. The specimen is seventeen feet long, and is being

mounted by my two sons, George and Charles, and myself, and is now nearly completed.

Our second camp proved very rich. Here we camped

southwest of Banner post office, in Trego county. Some

photographs I exhibit show some sculptured towers near Castle

Rock, a few miles west of our camp. George discovered a fine skeleton of a great

flying reptile Pteranodon. This also has gone to

the American Museum. One wing was complete, including the claw-armed fingers used in

clinging to rocks while at rest. Our bats hang head downward, while the Pteranodons hung

with head up.

The crowning discovery of our work here was the

discovery by George Sternberg of a nearly complete skeleton of a great shark, Lamna.

In 1891, while employed by the Munich Museum, I discovered the first and most complete

skeleton known of the shark Oxyrhina mantelli in the

same vicinity. This was made the subject of Dr. C. R. Eastman's inaugural address

delivered before0 the Ludwig-Maximilian University of Munich for his Ph.D. degree.

The specimen we collected on the south side of

Hackberry creek, South of Banner post office, in Trego county, includes the plates of the

mouth holding the teeth, of which some 150 are in sight, and the entire column of

flattened disk-like vertebræ to within five feet of the end of the tail. The total length

is about twenty feet of the preserved head and column. I think this will prove one of the

greatest scientific discoveries of the year, because the sharks are cartilagenous [sic],

and consequently their skeletons are not preserved. But in the two cases mentioned enough

bone was deposited to preserve the greater part of the skeleton. I further believe that

such, discoveries will prove that the ancient sharks do not reach the enormous proportions

that science has believed, owing to the size of the teeth. For instance, the great shark

of the Tertiary, Carcharodon megalodon, found along on the coast of South

Carolina, has enormous teeth, measuring six inches in length. By comparing them with the

living man-eating shark of

72

Kansas Academy of Science.

the same region today. Doctor Dean has restored a set of jaws measuring nine

feet across and having a gape of six feet.

In my specimen the largest tooth is an inch and a half

long while the smallest is but three-eighths of an inch. According to these measurements,

the ancient shark with teeth six inches long must have been 100 feet in length. That such

measurements cannot be relied on is proved by my discovery of a large part of the shark Corax,

from the Kansas chalk. The vertebræ proved to be as large as in Lamna and yet none

of the teeth were over half an inch in length. Further, I have in my laboratory to-day a

new species of shark, found this season on Hackberry creek whose vertebræ are half as

large as the Lamna we secured. The teeth are so small that some of them can only

be seen with a magnifying glass. It is pretty safe to restore one of these extinct sharks,

because their skeletons are so rare that they will in all likelihood never be discovered.

But I believe if these great teeth of the Carolinas are ever, as in my specimen, found in

place, the beautiful restoration in the American Museum will go to the junk pile.

On

the 23d of June my sons Charlie and Levi started with their team, wagon

and outfit to drive across northern

Kansas

and

Nebraska

to Cheyenne river, in Converse county,

Wyoming

, to take up the work we left off last year. I sent George in the meantime

to the rich fossil field at

Florissant

,

Colo.

Here he made a fine collection of leaves, fruit, flowers and insects from

the rich Tertiary shales. Then Charlie proceeded to

Wyoming

, joining George there, and I soon followed. What was my delight, on my

arrival at

Newcastle

,

Wyo.

, to learn that Charlie had been so fortunate as to discover a magnificent

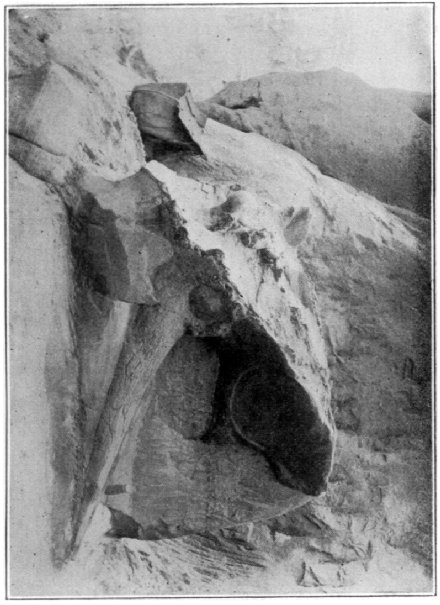

skull of the great I1'icel'atops, with horn cores thirty-three

inches long. This was sent to the

American

Museum

directly from the field. Professor Osborn writes, under date of December

19, 1907: "We have at last opened and examined the Triceratops skull,

and I am happy to write you that we are all delighted with it. It

promises to be a very

splendid specimen, worthy of the other great things which you have found.

The men are hopeful of restoring the frill." You will not wonder that

my delight knew no bounds when we made this discovery in a so-called

barren country. This country has been deserted for years because the

collectors who have spent many years there for Yale and Carnegie and the

American Museum had declared it

exhausted; and my party

of three sons have found, since we entered it last year, the

best specimen of the great duck-billed Trachodon ever known. This

discovery proves that all the existing mounts made up from

|

|

74

Kansas

Academy of Science.

eight

inches in diameter. This hill is across the

Cheyenne river

from our camp, above the mouth of Greasewood creek. I also show you the

skull of Triceratops as it lies, hewn out of the grey cross-bedded

sandstone, ready to wrap with burlap, soaked in plaster, so we can take it up ready for shipment. The horn-cores are in sight, as well as the

roof of the mouth, the eye socket under

the horn, and the nasal opening, the beak that was covered with horn, etc.

The frill had weathered out and lay in fragments, mingled with the debris

at the foot of the cliff. I might, in closing, mention the very fine tail

we found of Trachodon, the duck-billed dinosaur, as well as a

second, containing the entire trunk region. This, with the loose bones we

collected, will enable the

British

Museum

to make a very fine mount of this great dinosaur, some thirty feet in

length. I believe it

is the first specimen of

a large American dinosaur to be mounted in Europe, though a cast of the

great Diplodocus ca1'negie was sent to England, Germany and France,

and the great specimen mounted by the late Mr. Hatcher, its discoverer, in

Carnegie Museum, at Pittsburg. If

we live, you will hear

more of this barren region as we hope to enter that field as soon as the

frost is out of the ground. |