Marsh, O. C. 1873.

On a new sub-class of fossil birds (Odontornithes).

American Journal of Science. Series 3, 5(25):161-162.

Copyright © 2003-2009 by Mike Everhart

ePage created 12/23/2003; last updated 02/14/2009

Wherein Prof. O. C. Marsh announces the discovery of teeth in the type specimen of Ichthyornis and creates a new sub-class of birds, the Odontornithes (or birds with teeth). He acknowledges that he originally thought the jaws with teeth were from a small reptile (Colonosaurus Mudgei). However, he fails to give credit to the man who discovered the fossil, Prof. B. F. Mudge.

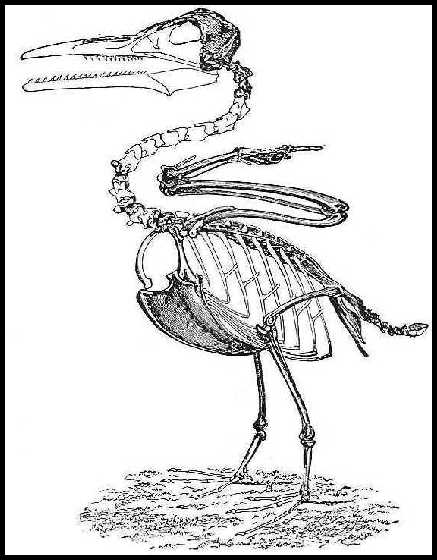

APPENDIX. ------ On a New Sub-class of Fossil Birds (Odontornithes); by O. C. MARSH. THE remarkable extinct birds with biconcave vertebrae (Ichthyornidae), recently described by the writer from the upper Cretaceous shale of Kansas, prove on further investigation to possess some additional characters, which separate them still more widely from all known recent and fossil forms. The type species of this group, Ichthyornis dispar Marsh, has well developed teeth in both jaws. These teeth were quite numerous, and implanted in distinct sockets. They are small, compressed and pointed, and all of those preserved are similar. Those in the lower jaws number about twenty in each ramus, and are all more or less inclined backward. The series extends over the entire upper margin of the dentary bone, the front tooth being very near the extremity. The maxillary teeth appear to have been equally numerous, and essentially the same as those in the mandible. The skull is of moderate size, and the eyes were placed well forward. The lower jaws are long and slender, and the rami were not closely united at the symphysis. They are abruptly truncated just behind the articulation for the quadrate. This extremity, and especially its articulation, is very similar to that in some recent aquatic birds. The jaws were apparently not encased in a horny sheath. The scapular arch, and the bones of the wings and legs, all conform closely to the true ornithic type. The sternum has a prominent keel, and elongated grooves for the expanded coracoids. The wings were large in proportion to the legs, and the humerus had an extended radial crest. The metacarpals are united as in ordinary birds. The bones of the posterior extremities resemble those in swimming birds. The vertebræ are all biconcave, the concavities at each end of the centra being distinct, and nearly alike. Whether the tail was elongated, cannot at present be determined, but the last vertebra of the sacrum was unusually large. This bird was fully adult, and about as large as a pigeon. With the exception of the skull, the bones do not appear to have been pneumatic, although most of them are hollow. The species was carnivorous, and probably aquatic. *This Journal, vol. iv, p. 344, Oct, 1872, and vol. v, p. 74, Jan., 1873. |

162

O. C. Marsh -- On a new sub-class of Fossil Birds When the remains of this species were first described, the portions of lower jaws found with them were regarded by the writer as reptilian;* the possibility of their forming part of the same skeleton, although considered at the time, was not deemed sufficiently strong to be placed on record. On subsequently removing the surrounding shale, the skull, and additional portions of both jaws were brought to light, so that there cannot not be any reasonable doubt that all are parts of the same bird. The possession of teeth and biconcave vertebræ, although the rest of the skeleton is entirely avian in type, obviously implies that these remains cannot be placed in the present groups of birds, and hence a new sub-class, Odontornithes (or Aves dentatæ), is proposed for them. The order may be called Ichthyornithes. The species lately described by the writer as Ichthyornis celer also has biconcave vertebræ, and probably teeth. It proves to be generically distinct from the type species of this group, and hence may be named Apatornis celer Marsh. It was about the same size as Ichthyornis dispar, but of more slender proportions. The geological horizon of both species is essentially the same. The only remains of them at present known are in the museum of Yale College. The fortunate discovery of these interesting fossils is an important gain to paleontology, and does much to break down the old distinctions between Birds and Reptiles, which the Archæopteryx has so materially diminished. It is quite probable that that bird, likewise, had teeth and biconcave vertebræ, with its free metacarpals and elongated tail. YALE COLLEGE, New Haven, Jan. 20th, 1873.

|

Suggested Reference:

Clarke, J. A. 2004. Morphology, phylogenetic taxonomy, and systematics of Ichthyornis and Apatornis (Avialae: Ornithurae). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 286: 1-179.