|

Mosasaurus hoffmanni - The First

Discovery of a Mosasaur?

Webpage created by Mike Everhart; Copyright ©

1999-2010

Last update - 05/14/2010

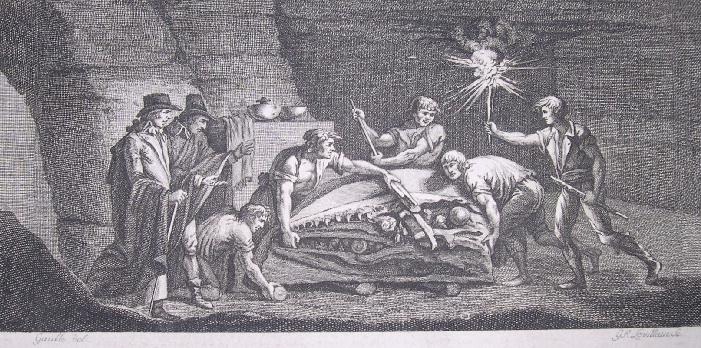

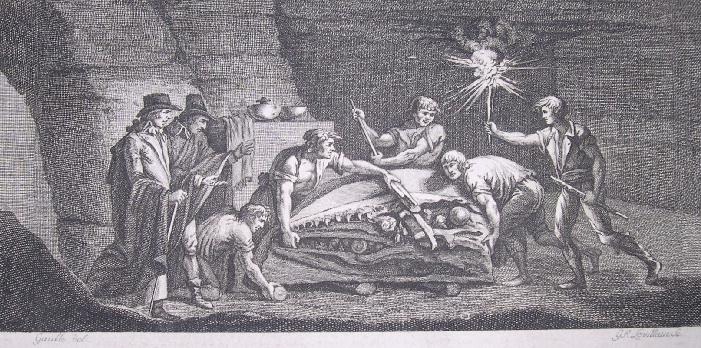

Left: Woodcut showing workers moving

a stone slab containing the skull of the first known mosasaur: Mosasaurus hoffmanni.

(Click for larger version) |

04/30/2004 - Translated into

French by Jean-Michel Benoit

The story is told of how the first mosasaur was found deep in an underground

mine near the River Meuse and purchased by Dr. J. L. Hoffmann ... Well, sometimes such

stories are more fiction than fact. This version (translated by Joseph Leidy from a

chapter in the book published by Faujas Saint Fond (1799)) was re-published by Williston

(1898; 1914) in his description of mosasaurs:

| 84

University of Kansas Geological Survey. ...

The first specimen of Mosasaurs of which we have

historical knowledge was discovered by Doctor Hoffman, a surgeon of Maastricht, in 1780,

and has been the subject of numerous descriptions and discussions by some of the most

famous naturalists of the world. Its discovery, and the subsequent destination of the

fossil, is the subject of the following account by M. Faujas-Saint-Fond, in his

"Natural History of St. Peter's Mount":

"In one of the galleries or subterraneous

quarries of St. Peter's Mount, at Maestricht, at the distance of about 500 paces from the

principal entrance, and at ninety feet below the surface, the quarrymen exposed part of

the skull of a large animal imbedded in the stone. They stopped their labors to give

notice to Doctor Hoffman, a surgeon at Maestricht, who had for some years been collecting

fossils from the quarries, and who had liberally remunerated the laborers for them. Doctor

Hoffman, observing the specimen to be the most important that bad yet been discovered,

took every precaution to secure it entire. After having succeeded in removing a large

block of stone containing it, and reducing the mass to a proper condition, it was

transported to his home in triumph. But this great prize in natural history, which bad

given Doctor Hoffman so much pleasure, now became the source of chagrin. A canon [Godding]

of Maestricht, who owned the ground beneath which was the quarry whence the skull was

obtained, when the fame of the specimen reached him, laid claim to it under certain feudal

rights and applied to law for its recovery. Doctor Hoffman resisted, and the matter

becoming serious, the chapter of canons came to the support of their |

WILLISTON.]

Mosasaurs.

85 reverend brother, and Doctor Hoffman not only lost the specimen but

was obliged to pay the costs of the lawsuit. The canon, leaving all feelings of remorse to

the judges for their iniquitous decision, became the happy and contented possessor of this

unique example of its kind.

"But justice, though slow, arrives at last. The

specimen was destined again to change its place and possessor. In 1795 the troops of the

French republic, having repulsed the Austrians, laid siege to Maestricht and bombarded

Fort St. Peter. The country house of the canon, in which the skull was kept, was near the

fort, and the general, being informed of the circumstance, gave orders that the

artillerists should avoid that house. The canon, suspecting the object of this attention,

had the skull removed and concealed in a place of safety in the city. After the French

took possession of the latter, Freicine, the representative of the people, promised a

reward of 600 bottles of wine for its discovery. The promise had its effect, for the next

day a dozen grenadiers brought the specimen in triumph to the house of the representative,

and it \vas subsequently conveyed to the museum of Paris."

It is said that after peace was established the canon

was reimbursed for the specimen. But it still remains in Paris.

....

Editor's note: The mosasaur remains were sent to Paris and in 1808, Baron

Cuvier published the first comprehensive description of "le grand animal fossile de

Maastricht." Cuvier agreed with Adrian Camper, noting that the fossil's relationships

lay somewhere between iguanas and varanid lizards. |

A more complete version of this story by Faujas Saint Fond is found in a 2004 translation from the original French text by Jean-Michel

Benoit.

However, in an 1872 book by W.H.D. Adams, (Life in the primeval

world.), on pages 204-207 we see another version:

V. THE MOSASAURUS, OR GREAT ANIMAL OF MAESTRICHT.

The history of the discovery of the Mosasaurus is an interesting geological

romance. And no animal has been the cause of more lively controversies among

scientific men - a race much given to controversy. Maestricht, we need hardly

tell the reader, is a city of the Netherlands, built on the banks of the Meuse.

Among the hills on the western side of the river a solid mass of cretaceous

formation known as St Peter's Rocks has long been the site of some extensive

quarries. Numerous fossil remains were at different times discovered here, and

an officer of the garrison, named Drouin, formed a collection which, in 1766,

was purchased by the authorities of the British Museum. Drouin's example was

followed by a military surgeon, named Hoffmann, who, in 1780, purchased of the

quarrymen a remarkable fossil head, upwards of six feet in length.

So great a prize attracted very general attention, and the Dean of the Chapter

of Maestricht, one Goddin or Godwin, was induced to claim it from its purchaser

on the ground that he was proprietor of the land where the fossil had been

exhumed. He brought an action at law in assertion of his right, was successful,

and received the much-coveted treasure.

In 1793 the French army, under General Kleber, laid siege to Maestricht.

Attached to the staff as Scientific Commissioner was the celebrated geologist,

Faujas de Saint-Fond. Of all the spoils of the city Faujas coveted only the

celebrated" head;" and, at his request, when Maestricht was bombarded,

Goddin's house was' spared, just as, of old,

“The great Emathian conqueror bid spare

The house of Pindarus, wben temple and tower

Went to the ground." (Milton, "Sonnets," viii.)

The city surrendered. Faujas hastened to Goddin's mansion; but the much-coveted

fossil had been removed. It is said that the representative of the people who

then accompanied the army promised six hundred bottles of good wine to the

soldier recovering the precious spoil. On the following morning twelve

grenadiers triumphantly brought it into the camp; it was packed with the utmost

care, and dispatched to the Museum of Natural History in Paris. It is but fair

to add that its former proprietor was compensated for his loss with a handsome

sum of money.

Faujas de Saint-Fond immediately occupied himself in studying his fossil, and

published the result of his investigations in a work entitled, "Histoire

naturelle de la Montagne de Saint-Pierre, pres Maestricht" but he had been

anticipated.

Pierre Camper and Van Marum had obtained possession of fragments of the same

animal, exhumed in the same locality. They had purchased them of the heirs of

the surgeon Hoffmann; and persisted in attributing them to a whale, contrary to

the opinion of their original owner, who had ascribed them to a crocodile.

Adrian Camper, in 1790, directing his attention to the same subject,

demonstrated that the "animal of Maestricht" was neither a whale nor a

crocodile, but a new genus of saurian akin to the existing monitor. He pointed

out, as specially distinguishing this saurian from a crocodile, the polish of

the bones, the apertures in the lower jaw for the egress of the nerves, the full

solid root of the teeth, the attachment of the teeth to the palate, as well as

certain obvious differences in the vertebrae. Faujas, however, refused to

abandon his theory, until Cuvier descended into the arena, and, with all his

wonted sagacity and insight, demonstrated its absurdity. The Mosasaurus (or

"lizard of the Meuse ") was neither a crocodile nor an iguana; and

these two animals, said Cuvier, differ as much from each other in their teeth,

bones, and viscera, as the ape differs from the cat, or the elephant from the

horse.

But while the great French anatomist was thus calmly demolishing the unfortunate

Faujas, he himself, no less than the Campers, was the victim of a skillful

imposture, which has only been recently discovered.

We have referred to certain supposed remains of the Mosasaurus as having been

purchased by Pierre Camper from the heirs of Hoffmann, the surgeon. These

remains were forgeries! The pieces described by the two Campers, and by Cuvier

himself, were mostly fabricated by Hoffmann; as Schlegel, in the course of his

studies of the Mosasaurus, has discovered. His exposure of this singular fraud

is contained in a letter addressed to Prince Charles Bonaparte, and by the

latter communicated to the French Academy of Sciences.

The sagacity of Adrian Camper had detected that the ossicles of the extremities

of the Mosasaurus had been glued by Hoffmann to a block of chalk from the

Maestricht quarries.

When Schlegel came to examine this block more closely, he not only

perceived the truth of Camper's observation, but ascertained that the same

artifice had been employed for a considerable number of other pieces described

by Camper, and, after him, by Cuvier. Hoffmann had not contented himself with

excavating holes in the blocks of chalk, in filling them with plaster, and

attaching to them the remains or fragments which he intended to sell; but had

united into one several diverse bony pieces, and changed their apparent

character by partly embedding

them in the plaster, and by placing them one upon another.

|

In 1822, the specimen finally

received its Linnean nominal when W. D. Conybeare referred to it as "Mosasaurus"

(Mosa-, the Latin name for the Meuse River near the town of Maastricht, and -saurus

for lizard. It was some years later when Gideon Mantell (1829:207) added the species name,

"hoffmanni" in honor of Dr. Hoffmann. |

|

NEW INFORMATION: In his recent book, Mulder (2003; pers.

comm. 2003), reported that the first mosasaur skull, somewhat less complete than the type

specimen of Mosasaurus hoffmanni Mantell 1829, was actually discovered in 1766,

near St. Pietersburg, Maastricht and is still on exhibit in the the Teylers Museum, in

Haarlem (No. TM 7424). Mulder also noted that the specimen of Mosasaurus hoffmanni

described above was actually found between 1770 and 1774 (not 1780), and was never

actually owned by Dr. Hoffmann. According the Mulder, the Canon Godding was the

first legal owner. Hoffman, however, was the person who corresponded with other scientists

of the day and who got the attention of Camper and Cuvier. Go HERE

for more pictures of early mosasaurs specimens in the Tylers Museum, Haarlem, The

Netherlands. Left: Photo of the partial skull of the first specimen

(1766) of Mosasaurus in the Teylers Museum. The photo of a second specimen is HERE. Photos by Menno Slaats. |

|

|

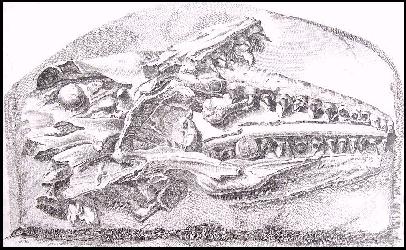

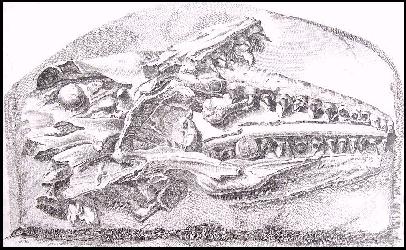

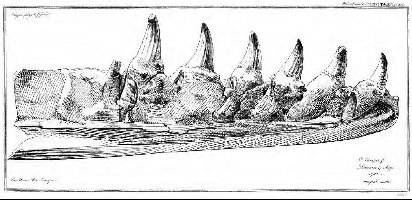

LEFT: ... and here's another twist.... This drawing

was published in 1790 by van Marum. According

to Mulder (2003), this is the "first documented find of a

mosasaur" occurred in 1766 at St. Pietersburg, Maastricht. The

specimen is still on display in the Tylers Museum in Haarlem, The

Netherlands... (no. TM 7424, ex Droulin Collection). Here

is a picture that I took of it in 2004 during the First Mosasaur Meeting.

|

|

|

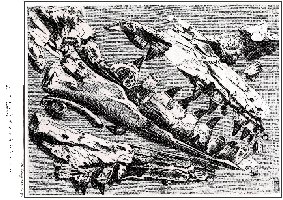

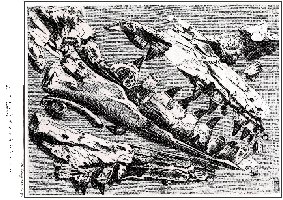

LEFT: As you might expect, there is a "rest of the

story"... Mosasaur bones had been seen before. In 1786 Pieter Camper

published a paper on "Conjectures relative to the petrifications found in St.

Peters Mountain near Maastricht." Although he was incorrect in regard to

the identification of the bones (he believed that they were whales) he did provide background

information on Dr. Hoffman that is considerably different than later

published by St. Fond and documented significant new

information about the creatures:

1) Comments on the pterygoid teeth

2) Comments on the openings in the dentary (foramina) for nerves

3) The first description of mosasaur vertebrae

4) Comments on tooth replacement

5) ...and he concluded that the specimen was not a crocodile.... |

|

|

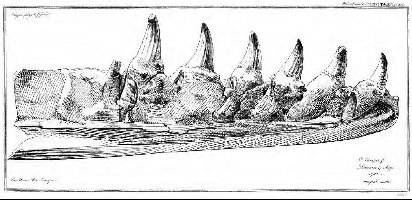

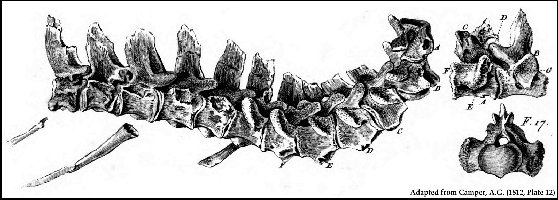

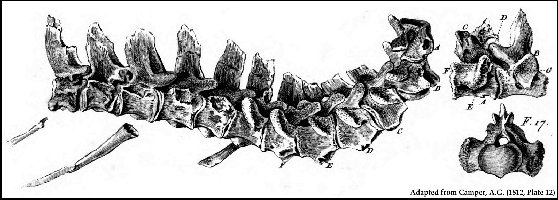

LEFT: Adrian Camper (son of Pieter Camper) was one of the

first to conclude (1800) that mosasaurs were closely related to Monitor

lizards, contra his father's idea that they were "whales." The

figures of mosasaur vertebrae at left were published in his 1812 paper. |

Credits:

The illustrations were adapted from "Mosasaurus hoffmanni, le Grand

Animal fossile des Carrieres de Maestricht: deux siceles d'histoire", by Nathalie

Bardet and John W. M. Jagt, Bulletin du Museum national d'Historie naturelle, Paris, 4

serie, 18, 1996.

The text is as credited above to Gordon L. Bell Jr. from Ancient Marine

Reptiles, 1997.

Photos from the Teylers Museum, Haarlem, by Menno Slaats.

References:

Adams, W.H.D. 1872. Life in the primeval world. London, 335 pp.

Bardet, N. and Jagt, J. W. M. 1996. Mosasaurus hoffmani, le

"Grand animal fossile des Carrieres de Maestricht": deux sicles d’histoire,

Bulletin de Museum d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, 4th Series, 18, Section C, No. 4, pp.

569-593.

Bell, G. L. Jr. 1997. Part IV:

Mosasauridae - Introduction. pp. 281-292 In Callaway J. M. and E. L Nicholls,

(eds.), Ancient Marine Reptiles, Academic Press, 501 pages.

Bell, G. L. Jr. 1997. A phylogenetic revision of North

American and Adriatic Mosasauroidea. pp. 293-332 In Callaway J. M. and E. L

Nicholls, (eds.), Ancient Marine Reptiles, Academic Press, 501 pages.

Camper,

A.G. 1800. Lettre de A.G. Camper à G. Cuvier, Sur les ossemens fossiles de la

montaague de St. Peter, à Maëstricht. Journal de Physique 51:278-291, pl. 1,

2.

Camper, A.G. 1812. Mémoire sur

quelques parties moins connues du squelette des saurians fossiles de Maëstricht.

Annales du Muséum d’Historie Naturelle 19:215-241.

Camper, P. 1786. Conjectures relative to the petrifications found in St.

Peters Mountain near Maastricht. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society

of London 76:443-456, pls. 15-16.

Leidy, J.

1865. Memoir on the extinct

reptiles of the Cretaceous formations of the United States. Smithsonian

Contributions to Knowledge 14(6):1-135, pls. I-XX.

Mulder, E.W.A. 2003. On latest Cretaceous tetrapods from

the Maastrichtian type area. Publicaties van het Natuurhistorisch Genootshap in Limburg,

Reeks XLIV, aflevering 1.Stichting Natuurpublicaties Limburg, Maastricht.

Saint Fond, F. 1799. Head of the Crocodile p. 59-67

in "Historie Naturelle de

la Montage de Saint-Pierre de Maestricht"; Translated from the French by

Jean-Michel Benoit.

Van Marum, M. 1790. Beschrijving der

beenderen van den kop van eenen visch, geveonden in den St. Pieterberg bij

Maastricht, en geplaatst in Teylers

Museum. Verhandelingen Teylers Tweede Genootschap 383-389, 1 plate, Haarlem.

Williston, S. W. 1898. Mosasaurs. The University

Geological Survey of Kansas, Part V. 4:81-347, pls. 10-72.