|

New specimen of shark scavenged

dinosaur (hadrosaur) remains from the Smoky Hill Chalk (Upper Coniacian) of western Kansas

Copyright © 2005-2014 by Mike Everhart

Page created 06/19/2005

Updated 03/08/2014

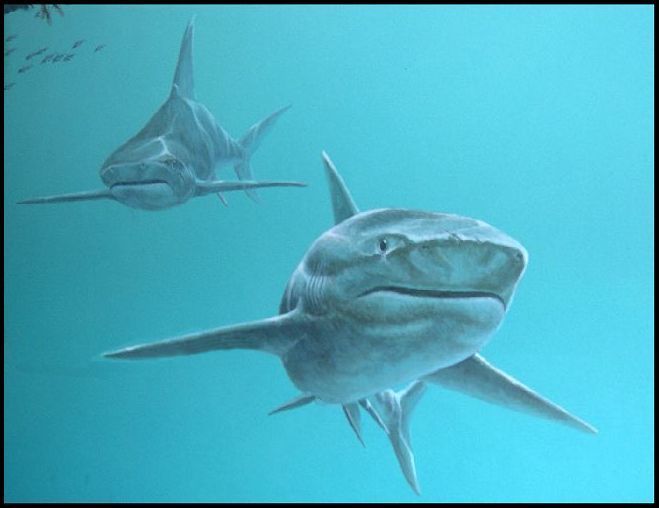

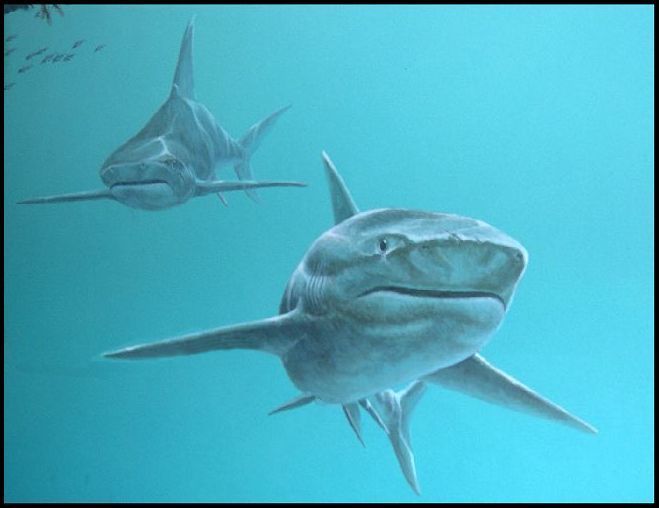

LEFT: Ginsu sharks (Cretoxyrhina

mantelli) on the prowl - Adapted from a portion of a mural in the University of

Nebraska State Museum, Lincoln, NE |

On June 2, 2005, I was with Keith Ewell when he discovered what is

only the sixth set of dinosaur remains to be documented from the Smoky Hill Chalk of

western Kansas. The first remains of a dinosaur found in the chalk, a hadrosaur, were

collected by O.C. Marsh in 1871 along the Smoky Hill River in

Logan County (see Carpenter, et al., 1995). The second set of remains, a nodosaur

(possibly two individuals, see Liggett, 2005) was discovered by Charles

Sternberg in 1905 and described by G. R. Wieland in 1909 and 1911. Virgil Cole

recovered the remains of another nodosaur in 1930 (Mehl, 1936; Cole, 2007) from

southeastern Gove County. This specimen (Niobrarasaurus coleii)

was transferred to the Sternberg Museum of Natural History in 2002 (Everhart, 2004) and

additional remains were recovered in 2003. J.D. Stewart found the fragmentary remains of

still another nodosaur (KUVP 25150) in Rooks County in 1973. The previous most

recent discovery of dinosaur remains was made by Shawn Hamm in 2000 when he collected the

right radius and ulna of a sub-adult nodosaur from the middle Santonian chalk of Lane

County (Everhart and Hamm, 2005). That specimen also preserved evidence of being scavenged

by a large shark.

The newest dinosaur specimen (FHSM VP-15824) comes from the lower

Smoky Hill Chalk in southeastern Gove County and consists of nine articulated caudal

(tail) vertebrae from an adult hadrosaur (credit for the ID goes to Ken Carpenter). The

vertebrae were laying on their right side. The most anterior vertebrae (#1 and #2) of the

series had partially eroded out and were exposed on the surface of the chalk. The other

seven vertebrae were still completely enclosed in the matrix. The specimen is 22 in (55

cm) in length, is from the distal part of the tail and represents an adult animal that was

about 10 m in length. There are non-serrated bite marks on both sides of the last

vertebrae (#9, see pictures below). The bone surface at both ends of the articulated

series are severely eroded and appear to have been partially digested. Consistent with

many other specimens of large vertebrates (mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, turtles, etc) from this

time period during the deposition of the Smoky Hill Chalk, these remains appear to have

been consumed by a large shark, partially digested and then

regurgitated. See Everhart and Ewell (2006) for additional information.

Gudger (1949, p. 41) reported finding a cow's skull in the stomach

of a modern Tiger shark caught off the coast of Florida, and that "…the

outer hard smooth layer of the skull bones everywhere had been dissolved leaving only the

inner cellular or cancellous material. This in turn was so soft that one could dent it

with a finger. The digestive juices of a shark's stomach (presumably chiefly hydrochloric

acid) are very concentrated." In another instance, he (ibid., p. 42) reported finding

a horse's skull in the stomach of another Tiger shark and that the "outer hard smooth surface of the horse's skull had all

been corroded away leaving the cancellous material about the consistency of sponge-rubber."

|

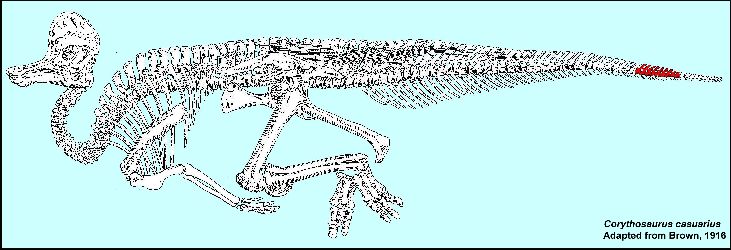

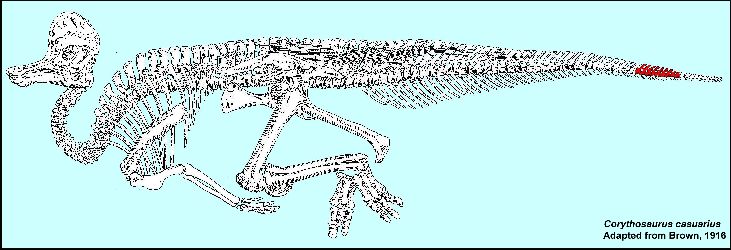

LEFT: (LARGE FILE): The red vertebrae

indicate the approximate location of the specimen in a drawing of the tail of the Late

Cretaceous hadrosaur, Corythosaurus

casuarius (adapted

from Brown, 1916). |

The new specimen represents the first (and the earliest) remains of a hadrosaur

to be collected from the Smoky Hill Chalk in more than 130 years. The type specimen of Claosaurus

agilis was found by O.C. Marsh about 50 miles further west, on the north side of the

Smoky Hill River, in Logan County, and much higher (a couple million years later) in the

chalk. It was also a much smaller individual, estimated by Marsh (1890) to be about 15

feet long. Questions remain in regard to how the remains of these dinosaurs managed to

drift hundreds of miles from land before final burial on the bottom of the Western

Interior Sea.

|

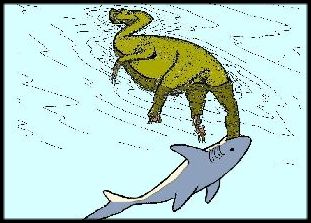

LEFT: My view of a large Cretoxyrhina mantelli shark

scavenging on the tail of a dead hadrosaur floating in the Western Interior Sea. Drawing

adapted from the original illustration by William J. Frazier in a Dinofest International

paper by David Schwimmer (1997). Used with permission. |

|

LEFT: An articulated series of nine caudal vertebrae (FHSM

VP-15824) in left (upper) and right lateral view from a dinosaur discovered in the Smoky

Hill Chalk of western Kansas by Keith Ewell, June, 2005. According to Ken Carpenter, the

long, slender neural spines are distinctive to hadrosaurs. (Scale = cm) |

|

LEFT: Posterior (upper) and dorsal views of the caudal vertebrae

(FHSM VP-15824) - most anterior to the left. (Scale = cm) RIGHT:

Vertebrae #7, 8 and 9 in left lateral view, showing the articulation between the elongated

neural spines and the following vertebra. (Scale = cm) |

|

|

LEFT: Vertebra #2 (left) and #1 (right) in anterior (cranial) view

showing the amount of damage done to the exposed end of the most anterior vertebra (#1) in

the series by the acids in the shark's stomach. RIGHT: Vertebra #8

(left) and #9 (right) in posterior (caudal) view showing the damage done to the most

posterior vertebra (#9) by exposure to the acids in the shark's stomach. (Scale = cm) |

|

|

LEFT: The most distal of the vertebrae in the series (#9) in right

lateral, proximal end and left lateral view. It preserves deep, non-serrated (e.g.,

NOT Squalicorax falcatus) bite marks on both sides of the vertebrae.

This is probably an indication of an earlier bite that severed the tip of the tail. There

is also evidence of severe erosion of the bone surface, probably due to exposure to

digestive fluids in the shark's stomach. Little or no damage due to digestion is visible

on the interior vertebrae of this series, most likely because they were covered with

enough skin, muscle and connective tissue to provide some degree of protection. (Scale =

cm) |

|

LEFT: Left lateral and dorsal views of the most

complete vertebrae (#5). (Scale = cm) RIGHT: A close-up of vertebrae

#5 and #6 with re-attached neural spines. |

|

|

LEFT: (Click to enlarge) An unusual Squalicorax sp.

tooth (FHSM VP-16355) in labial (left) and lingual views that was found in situ

under the dinosaur vertebrae. Note the very weak serrations on the main cusp and the lack

of serrations on the posterior accessory cusp. These teeth are fairly common in the

lower chalk (below MU 9) and may represent an undescribed species. |

|

LEFT AND RIGHT: The site where the specimen was collected in the

lower chalk (Upper Coniacian) of Gove County, Kansas. The rock pick is about 16 inches (40

cm) long. Marker Unit 4 (Hattin, 1982) appears as a series of reddish-brown iron

concretions about a half meter under the specimen. This site is about a mile north of the

type locality of Niobrarasaurus coleii (FHSM VP-14855) and slightly higher in the

rock column (both Upper Coniacian). |

|

|

LEFT: For comparison, a series of distal caudal vertebrae (left

lateral view) from the type specimen of Niobrarasaurus coleii (FHSM

VP-14855) in the collection of the Sternberg Museum of Natural History.

RIGHT: Three caudal vertebrae from FHSM VP-14855 in left lateral and dorsal

view. (Scale = cm) |

|

|

LEFT: A juvenile nodosaur caudal vertebra (FHSM VP-16385) found by

Keith Ewell in 2004 in southwestern Trego County (Smoky Hill Chalk - Upper Coniacian). The

vertebra appears to be partially digested, most likely by a large shark. Approximately

life-sized. Keith is now the only person in 134 years to ever find the remains of

two dinosaurs in the Smoky Hill Chalk. |

|

EIGHTH DINOSAUR SPECIMEN FOUND IN THE SMOKY HILL CHALK (FHSM

VP-17229) LEFT: Over the Memorial Day weekend in 2007, Laura and Scott

Garrett were prospecting for fossils in the lower Smoky Hill Chalk (below Hattin's Marker

Unit 3 - Late Coniacian) of southwestern Trego County. Laura found an isolated anterior

caudal vertebra (near the base of the tail) from what appears to be a large ankylosaur,

most likely Niobrarasaurus coleii. Note that this vertebra is very

similar to, but much larger than, the one collected by Keith Ewell in 2004 (above). Laura

becomes the first woman (and only the 7th person) to ever collect dinosaur remains from

the Smoky Hill Chalk. The Garretts generously donated the specimen to the Sternberg Museum

of Natural History (VP-17229). The specimen comes from about 6 miles south of the site

where VP-16385 was collected in 2004, and from about 5 miles east of where the type

specimen of Niobrarasaurus coleii (VP- 14855) was collected in 1930. All are Late

Coniacian in age. |

|

LEFT: A remains of an isolated and partially digested dorsal

mosasaur vertebrae (FHSM VP-16356) in ventral, right lateral and dorsal views, that is

comparable in size to the hadrosaur caudal vertebrae above. In this case, however, the

vertebra was severely damaged by the digestive fluids and a tip of a shark tooth (circles)

remains embedded in the bone. Note the damage to the surface of the bone. The flattened

appearance is due mostly to post-mortem crushing. Click here for a close-up of the embedded Cretoxyrhina

mantelli tooth (FHSM VP-16357). |

Suggested references:

Brown,

B, 1916. Corythosaurus casuarius: Skeleton, musculature and epidermis.

Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 35: 709-716, pls. xiii-xxii.

Carpenter, K., D. Dilkes, and D. B. Weishampel. 1995. The

dinosaurs of the Niobrara Chalk Formation (upper Cretaceous, Kansas). Journal of

Vertebrate Paleontology 15(2): 275-297.

Carpenter, K. and Everhart, M. J. 2007. Skull of the ankylosaur Niobrarasaurus

coleii (Ankylosauria: Nodosauridae) from the Smoky Hill Chalk (Coniacian) of western

Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions, 110(1/2): 1-9

Cole, V. B. 2007.

Field

notes regarding the 1930 discovery of the type specimen of Niobrarasaurus coleii, Gove County, Kansas. Kansas

Academy of Science, Transactions 110(1/2): 132-134.

Eaton, T. H. Jr., 1960. A new armored dinosaur from the Cretaceous of Kansas.

University Kansas Paleontology Contri. 8:1-14, 2 fig. (Silvisaurus)

Everhart, M. J. 2003. First records of plesiosaur remains in the

lower Smoky Hill Chalk Member (Upper Coniacian) of the Niobrara Formation in western

Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 106(3-4): 139-148.

Everhart, M. J. 2004. Late Cretaceous interaction between predators and prey. Evidence of feeding by two species of shark on a mosasaur. PalArch,

vertebrate palaeontology series 1(1): 1-7.

Everhart, M. J. 2004. Notice of the transfer of the holotype

specimen of Niobrarasaurus coleii (Ankylosauria; Nodosauridae) to the Sternberg

Museum of Natural History. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 107(3-4): 173-174.

Everhart, M. J. 2005. Bite marks on an elasmosaur (Sauropterygia;

Plesiosauria) paddle from the Niobrara Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) as probable evidence of

feeding by the lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli. PalArch, Vertebrate

paleontology 2(2): 14-24.

Everhart, Michael J. 2005. Oceans of Kansas - A Natural

History of the Western Interior Sea. Indiana University Press, 320 pp.

Everhart, M. J. and K. Ewell.

2006. Shark-bitten dinosaur (Hadrosauridae) vertebrae from the Niobrara Chalk

(Upper Coniacian) of western Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions, 109

(1-2):27-35. (copies available on request in .pdf format)

Everhart, M. J. and S. A. Hamm. 2005. A new nodosaur specimen

(Dinosauria: Nodosauridae) from the Smoky Hill Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) of western Kansas.

Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 108(1/2): 15-21.

Gudger, E.W.

1949. Natural history notes on tiger sharks, Galeocerdo tigrinis, caught in

Key West, Florida with emphasis on food and feeding habits. Copeia 1949: 39-47, pl. 1-2.

Liggett, G. A. 2001. Dinosaurs to Dung Beetles: Expeditions

through time - A guide to the Sternberg Museum of Natural History. Sternberg Museum

of Natural History, Hays, KS. 127 p.

Liggett, G. A. 2005. A review of the dinosaurs from Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science.

Transactions 108(1/2): 1-14.

Lull, R. S., and Wright, N.E. 1942. Hadrosaurian dinosaurs of North America.

Geological Society of America Special Paper 40, xii + 242 p., 90 figs., 31 pls.

Hamm, S. A. and M. J. Everhart. 2001. Notes on the occurrence of

nodosaurs (Ankylosauridae) in the Smoky Hill Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) of western Kansas.

Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 21(suppl. to 3): 58A.

Hattin, D. E. 1982. Stratigraphy and depositional environment of the Smoky Hill Chalk

Member, Niobrara Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) of the type area, western Kansas. Kansas

Geological Survey Bulletin 225, 108 pp.

Marsh, O. C. 1872. Notice of a new species of Hadrosaurus.

American Journal of Science, Series 3, 16: 301.

Marsh, O.C. 1890. Additional characters of the

Ceratopsidae, with notice of new Cretaceous dinosaurs. American Journal of

Science, Series 3, 39(233): 418-426, with pls. v-vii.

(The renaming of Hadrosaurus agilis to Claosaurus agilis)

Mehl, M. G. 1931. Aquatic dinosaur from the Niobrara of western

Kansas. Bulletin of the Geological Society of America 42: 326-327.

Mehl, M. G. 1936. Hierosaurus coleii: a new aquatic dinosaur from the Niobrara

Cretaceous of Kansas. Denison University Bulletin, Journal of the Scientific Laboratory

31: 1-20, 3 pls.

Parmenter, C. S. 1899. Fossil turtle cast from the Dakota epoch. Kansas Academy of

Science, Transactions 16: 67.

Schwimmer, D. R. 1997. Late Cretaceous dinosaurs in eastern

U.S.A.: A taphonomic and biogeographic model of occurrences. Dinofest International,

Proceedings of a Symposium sponsored by Arizona State University, p. 203-211.

Schwimmer, D. R., J. D. Stewart, and G. D. Williams. 1997. Scavenging by sharks of the

genus Squalicorax in the late Cretaceous of North America, PALAIOS, 12:71-83.

Schwimmer, D. R., G. D. Williams, J. L. Dobie, and W. G. Siesser. 1993. Late Cretaceous

dinosaurs from the Blufftown Formation in western Georgia and eastern Alabama. Journal of

Paleontology 67: 288-296. (remains from marine sediments)

Shimada, K. 1997. Paleoecological relationships of the late

Cretaceous lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli (Agassiz). Journal of

Paleontology. 71(5): 926-933.

Shimada, K. and G. E. Hooks, III. 2004. Shark-bitten protostegid turtles from the Upper

Cretaceous Mooreville Chalk, Alabama. Journal of Paleontology 78(1):205-210.

Sternberg, C. H. 1909. An armored

dinosaur from the Kansas chalk. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 22: 257-258.

Stewart, J. D. 1990. Niobrara Formation vertebrate stratigraphy. Pages 19-30, In Bennett,

S. C. (ed.), Niobrara Chalk Excursion Guidebook, The University of Kansas Museum of

Natural History and the Kansas Geological Survey.

Varricchio, D. J. 2001. Gut contents from a cretaceous tyrannosaurid; Implications for

theropod dinosaur digestive tracts. Journal of Paleontology 75(2):401-406.

Wieland, G. R. 1909. An armored saurian. American Journal of Science 27: 250-252. (March)

Wieland, G. R. 1909. A new armored saurian from the Niobrara. Contributions to the Peabody

Museum, XIX: 250-252

Wieland, G. R. 1911. Notes on the armored Dinosauria. American Journal of Science 31:

112-124.