|

Xiphactinus audax Leidy 1870

(...not Portheus molossus

Cope 1872)

Largest Bony Fish of the Late

Cretaceous Seas

Copyright © 2000-2013 by Mike Everhart - Last revised

08/01/2013

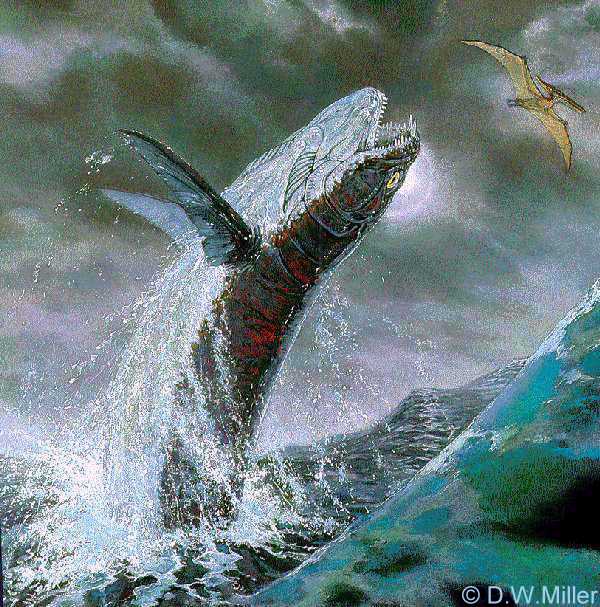

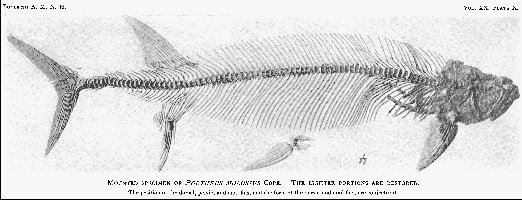

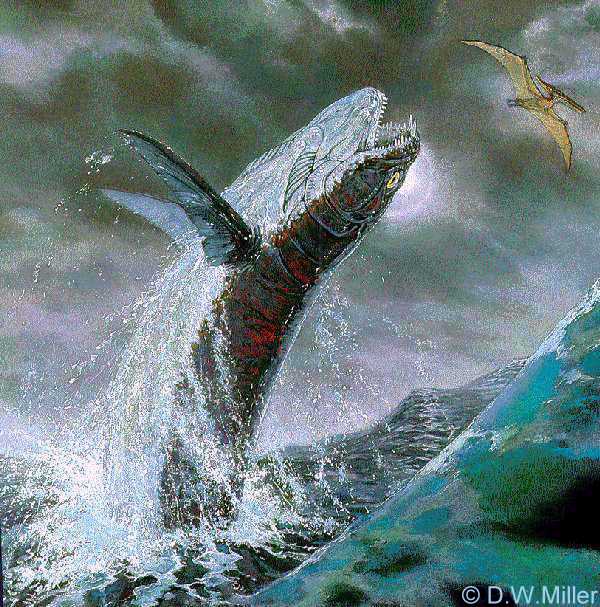

LEFT: This Xiphactinus audax

shown in mid-jump in a painting by D.W. Miller...

Note that the

jaws of the fish are about 8-10 feet above the surface of the water. That's BIG!! © D. W. Miller, used with permission. |

|

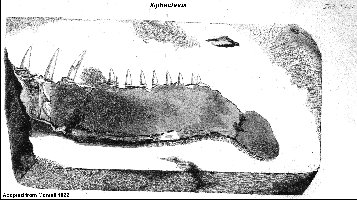

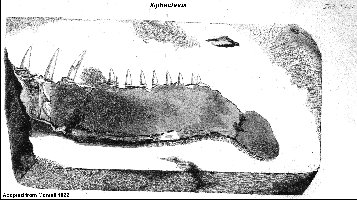

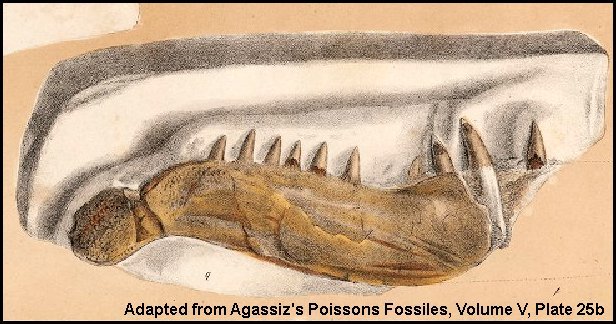

Recently I came across a figures in Mantell's 1822 work, The Fossils of South Downs

(LEFT) and a Mantell's 1833 Geology of the

South-East of England (RIGHT- reversed) that undoubtedly represents a specimen of

a small Xiphactinus. The total length of the jaw is given as about

5 inches. In the second book, he regarded the jaw as belonging to an

unknown reptile (See description below). A recent check with the

British Museum of Natural History indicates that the specimen is still

there and is curated as BMNH (OR)4066.

Note that this specimen was fully reported by O.P. Hay in 1898:

"The earliest reference which we have to any remains of

the genus of fishes usually called Portheus

is that found in Mantell's Geology

of Sussex, p. 241, P1. XLII, 1822. No systematic name is there

assigned to this fish. Later, Louis Agassiz, in his Poissons

Fossiles, vol. v, p. 99, referred to Mantell's description, and

refigured the materials (op. cit., PI. XXV b, Figs. I a, I

6),presenting at the same time additional figures of remains from the same

locality (Pl. XXV a, Fig. 3; P1. XXV b, Figs. 2, 3). All these he

included, with other remains, under the name Hypsodon

lewesiensis."

|

|

|

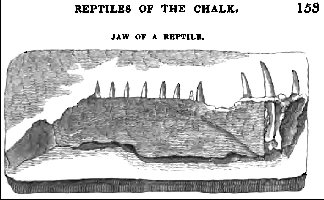

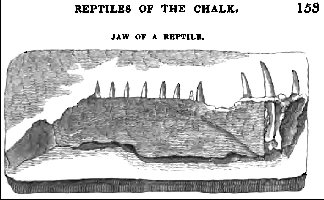

From

Mantell, 1833, p. 152-153:

"Undetermined

Reptiles. - A lower jaw, with twelve

smooth, pointed, slightly convex teeth, was figured

in the Fossils of the

South Downs

, as the jaw of a fish. There can scarcely admit of a doubt that it

belongs to a saurian animal: a figure is annexed. The original is

five inches long; the fangs of the anterior teeth, like those of

the crocodile, are hollow, fixed in sockets, and not attached to the jaw;

but their smooth polished surface, and flattened form, separate them most

decidedly from the animals of that family. The posterior teeth are affixed

to the edge of the jaw, a mode of dentature observable

in many kinds of fishes. The structure of a vertebra found with the jaw is

decidedly that of a fish, the conical cavities being very deep; and it

possesses the annular markings so constantly observable in the vertebrae

of fishes. A cylindrical bone was also found, but was too much injured to

allow of any correct inference being drawn from it.

The posterior extremities of a lower

jaw of a reptile were found in the same block of chalk, with

portions of the upper and lower

maxillae bearing many teeth, and corresponding with those of the last

mentioned fossil; and fragments of other maxillae have since been

discovered: the materials at present in

my possession are, however, too

imperfect to admit of the zoological relations of these remains being

accurately determined." So

after identifying the specimen as the lower jaw of a fish in 1822, Mantell

changed his mind and decided it was actually the jaw of an unidentified

reptile in 1833. |

|

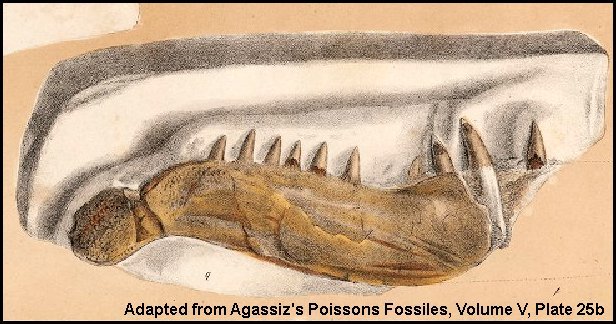

LEFT: But the story doesn't end there..

Louis Agassiz in Volume 5 of his "Recherches sur les Poissons

Fossiles" (1833-1845) published yet another drawing of the

specimen on Plate 25b, correctly regarded it as the jaw of a fish, and

gave it a name - "Hypsodon lewesiensis." (see page 99).

Newton (1877) revisited this specimen and others, and correctly

identified the specimen as "Portheus" then based on the

number of teeth in the premaxilla (5), gave it a new species name, Mantelli,

close to Cope's "P. lestrio" and "P.

Mudgeii" (see page 510).

The story was recounted again by O.P. Hay (1898) in his paper noting

that Xiphactinus Leidy was the senior synonym of Portheus

Cope (Observations on the genus of fossil fishes called by

Professor Cope, Portheus, by Dr. Leidy, Xiphactinus).

Bardack (1965) was the next to discuss the specimen in his "Anatomy and evolution of Chirocentrid

fishes." According to Bardack (p. 37), Agassiz had originally named the

specimen Megalodon in 1835, but upon finding the genus name

preoccupied, changed it to Hypsodon in 1837. He also notes

that the first Hypsodon species named by Agassiz is a

pachyrhizodid, not an ichthyodectid, so Leidy's genus is valid and has

priority. |

|

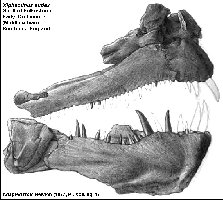

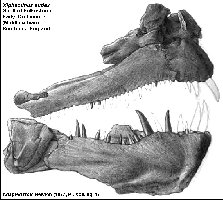

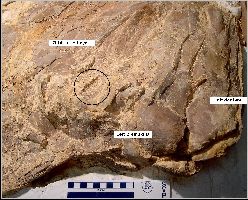

LEFT: The partial skull of an Early Cretaceous (Middle

Albian) Xiphactinus audax from southeastern England figured by

Newton (1877, p. 512, plate XXII, fig. 1):

Portheus

gaultinus, n. sp. PI. XXII. figs. 1-12.

Mrs.

Elizabeth Warne has recently enriched the

Museum

of

Practical Geology

by the presentation of a very fine specimen of Portheus, which was

obtained through Mr. E. Charlesworth, from the Gault of Folkestone. This

specimen includes the greater part of upper and lower jaws of both sides,

with a considerable portion of the brain-case and bones of the ethmoidal

region, also several vertebrae and fragments of bones which cannot be

identified. The generic relationship of this specimen to the American Portheus

cannot be doubted; specifically

it is so closely allied to P. lestrio, Cope, that one might at

first be inclined to refer it to that species; but, besides its much

smaller size, it exhibits certain peculiarities which prevent its

being regarded as the same. Each of the parts will now be considered

separately. |

Back to the Western Interior Sea....

After his 1871 trip to Kansas, E.D. Cope (1872a) was reported to

have said, "At a similar location on Fox Creek, M. V. Hartwell found the skeleton of

a very large fish, with "uncommonly powerful offensive dentition," probably of

the Saurodonts. He [Cope] names this Cretaceous species Portheus

molossus.

In a later report Cope (1872b) wrote, "The head was as long

or longer than that of a fully grown grizzly bear, and the jaws were deeper in proportion

to their length. The muzzle was shorter and deeper than that of a bull-dog. The teeth were

all sharp cylindric fangs, smooth and glistening, and of irregular size. At certain

distance in each jaw they projected three inches above the gum, and were sunk one inch

into the jaw margin, being thus as long as the fangs of a tiger, but more slender. Two

such fangs crossed each other on each side of the middle of the front. This fish is known

as Portheus molossus, Cope [a junior synonym of Xiphactinus audax

Leidy 1870]. Besides the smaller

fishes, the reptiles no doubt supplied the demands of his appetite."

"The Portheus, now swimming for life, was the foci of the

sharks that were coming to the attack from all directions. One would dive under the fish,

and receive, for his pains, a stroke from his powerful tail that would put him out of

commission; another would receive a thrust from the sword-like ray of the front fin.

Undaunted, others hurried up like a pack of wolves on a wounded deer. Though many were

wounded in the fray, our hero fish at last succumbed to numbers, who gashed his body with

their lance-like teeth, and the water was tinged with his life blood, until, weakened and

overpowered, he gradually ceased struggling. The sharks gathered to the feast. One,

however, was so badly wounded by the Portheus,

that he went to the oozy bottom with him. I have preserved in the Museum of the University

of Kansas a shark twenty-five feet long, and mingled with his remains were the bones of a Portheus, the evident result of such a combat …

“

Excerpted from Charles H. Sternberg's

"Hunting Dinosaurs on the Red Deer River, Alberta, Canada" (1917, p.

162). While the passage from C H. Sternberg's book is fiction, it is based on the

discovery of the remains (KUVP 247) of a large Cretoxyrhina mantelli (Ginsu shark)

that also contains the scattered bones of a large Xiphactinus as its last meal. The

specimen is on exhibit in the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History in Lawrence,

Kansas (below) |

|

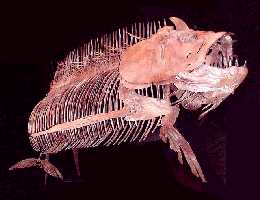

LEFT: Sometimes, the tables were turned and the hunter became the

meal. This is photograph of a disarticulated shark specimen (KUVP 247) at the

University of Kansas Museum of Natural History. The most interesting thing about the find

was the remains of a large Xiphactinus audax inside the shark when it died.

Note the large lower jaw, with teeth, in the upper center of this picture. Xiphactinus

ribs are also scattered among the shark vertebrae. The

skull of the shark (Cretoxyrhina mantelli) was preserved with dozens of

teeth still in place in the jaws. (Found by George Sternberg, 1908 and described by

Charles H. Sternberg in 1917 (see above note).

RIGHT: The left maxilla of a shark scavenged Xiphactinus

(KUVP 12011) with some of the many Cretoxyrhina mantelli teeth that were

discovered in association with the remains.

|

|

|

Xiphactinus audax, [Zy-fac-tin-us] or as it

is more commonly called, the "Bulldog Fish", was a species of very large

predatory fish that lived in the ocean during the Late Cretaceous. LEFT:

A detailed drawing by Prentice of the skull of Xiphactinus from volume 6 of the

University Geological Survey of Kansas (Stewart, 1900). LARGE FILE

RIGHT: The articulated skull of a large Xiphactinus audax in

our collection in right lateral view (scale = 10 cm). This specimen was found by my wife

in 1989 in Gove County. The skull was prepared out by Katie Conkling in 2007, including the discovery

of two Squalicorax falcatus teeth lying on the sagittal crest. (A view of

partially prepared left side of the skull is HERE) The

"Evil Eye" was added by her son, Mike.... |

|

|

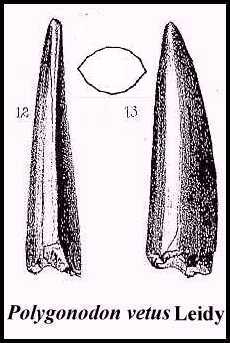

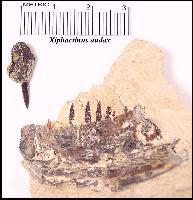

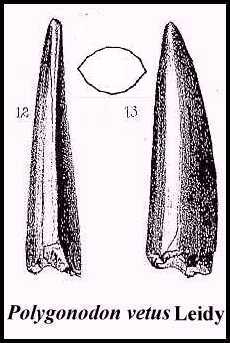

RELATED HISTORICAL NOTE: Leidy (1856) gave a

short description of a single tooth found in the Cretaceous marl of New Jersey and named

it Polygonodon vetus:

"Based on a specimen of the crown of a tooth found in the marl

(cretaceous) of Burlington County by L. T. Germain, Esq., Length three times

the breadth; transverse section elliptical; with trenchant borders; with six planes on one

side and seven on the other. Length 1½ inches, breadth ½ an inch. May be an incisor of Mososaurus

[sic]?"

Leidy (1865) described the tooth in greater detail and included three figures

(left) showing what it looked like in (12) posterior, (13) external view, and in cross

section. Still believing the tooth to be reptilian, he thought it "may have belonged

to Discosaurus or Cimoliasaurus, but the matter must be left for future

determination."

The tooth was later determined to be from a sister species of Xiphactinus

audax, raising the issue of which genus name should have priority... Polygonodon

Leidy 1856 or Xiphactinus Leidy 1870?

See Schwimmer, et al. (1997) for a more

detailed explanation. Most likely it will remain Xiphactinus. |

|

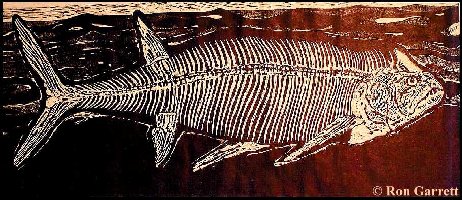

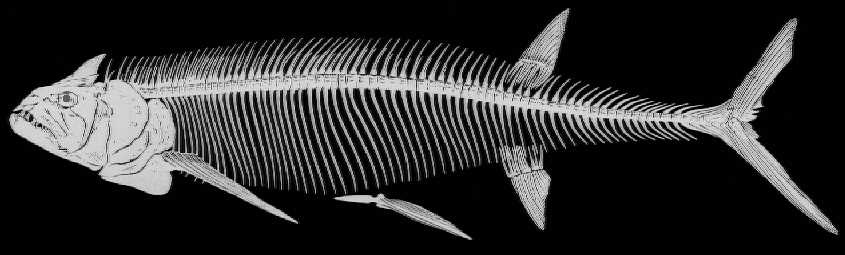

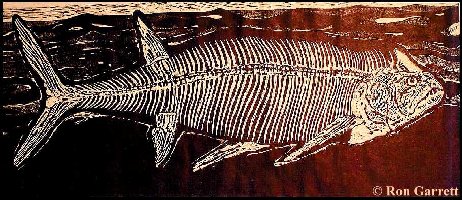

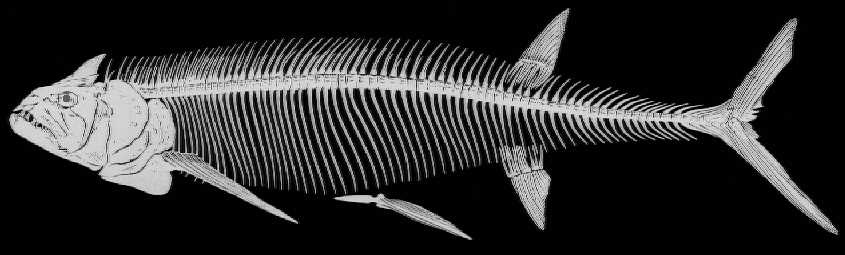

Although they were not closely related, a Xiphactinus

would have looked much like a modern Tarpon. The fish probably attained lengths of 18 to

20 feet, and some 'giant vertebrae' from marine deposits in Arkansas indicate that some

individuals that were even larger. Xiphactinus

audax painting and skeleton woodcut © Ron Garrett, used with permission of Ron Garrett |

|

|

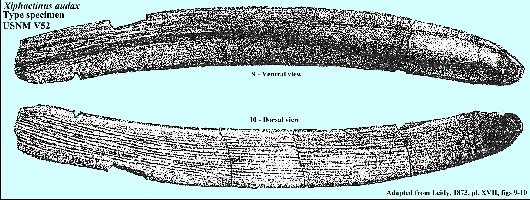

While the name Xiphactinus has been around since 1870,

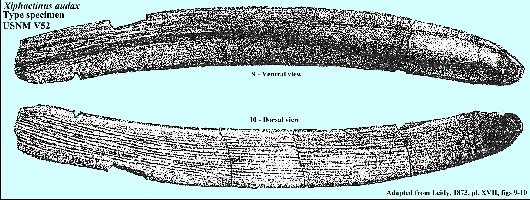

there has been considerable confusion over which name is actually correct? : Xiphactinus audax (Leidy, 1870) or Portheus molossus (Cope, 1872). LEFT:

In 1870, Joseph Leidy named the fish from a 16 inch (40.6 cm) long fragment of a pectoral fin ray (USNM V52), collected

by Dr. George M. Sternberg, more than a year before E. D. Cope

gave the name of Portheus molossus to a collection of several nearly complete

specimens found near Fort Wallace. Leidy's name is correct by virtue of being the

first to be published, but Cope's name was more popular and is still in use (incorrectly)

in many collections of Cretaceous fish. |

|

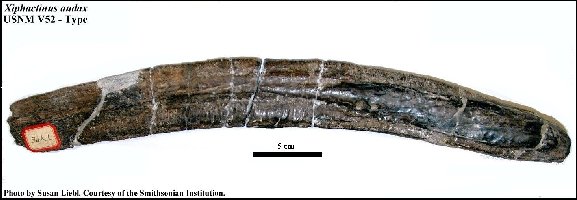

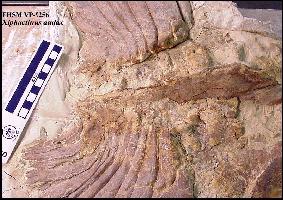

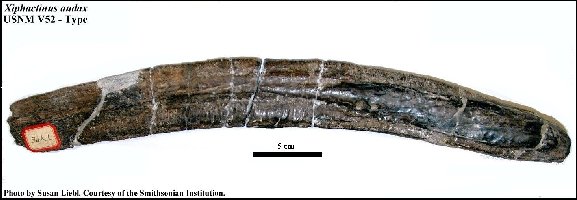

LEFT: A 2009 photo of the USNM V52 Xiphactinus audax type

specimen in ventral view. Photograph by Susan Liebl (Copyright © Susan

Liebl, used with her permission, and courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution, United

States National Museum, Washington, D.C). |

|

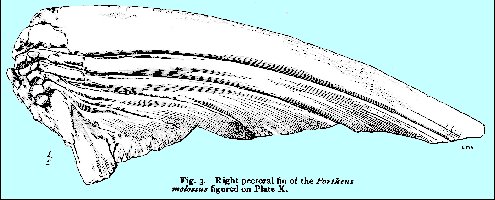

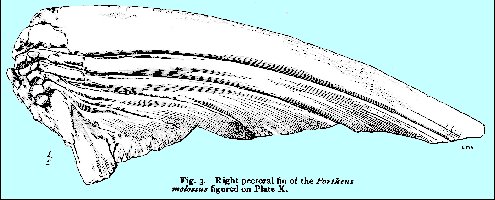

LEFT: The right pectoral fin (dorsal

view) of Xiphactinus audax from Osborn (1904). The specimen (above)

collected by Dr. Sternberg and used as the type species of Xiphactinus by Leidy

would have been the largest fin ray at the top of the figure.

Note here that prominent paleontologists like

Osborn were largely responsible for continuing the usage of the junior

synonym (Portheus molossus) even though it had been corrected

earlier by O.P. Hay (1898), and A. Stewart (1898). |

|

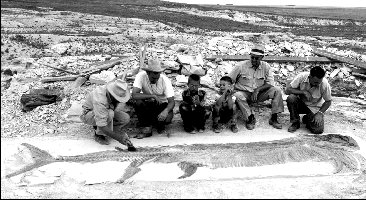

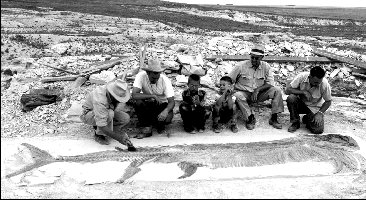

LEFT: The fossilized remains of these fish, especially skull fragments

and vertebrae, are fairly common in the Smoky Hill Chalk. Sometimes, the

skeletons are very complete, such

as this famous fossil of a "fish-within-a-fish" excavated by George F. Sternberg

in 1952 (George is on the far left in the picture). This specimen is about 13 feet long and is on permanent display in

the Sternberg Museum in Hays, Kansas. The six foot long, 'last' meal' is a related species

of ichthyodectid fish called Gillicus arcuatus.

George F. Sternberg was the

nephew of the Dr. George M. Sternberg who sent the original Xiphactinus

type specimen from Kansas to Dr. Joseph Leidy sometime before 1870. |

|

LEFT: The famous "fish-within-a-fish"

Xiphactinus audax specimen (FHSM VP-333) at the Sternberg

Museum of Natural History (Click picture to see much larger version (190 kb). The

stomach contents (a large Gillicus arcuatus) is curated as FHSM VP-334. The Xiphactinus

is just over 13 feet long. Contact me for a

copy (.pdf file) of Myrl V. Walker's account of the discovery and recovery of this famous

specimen: "The Impossible Fossil." It's an interesting historical account and a

great description of the "Sternberg method." |

|

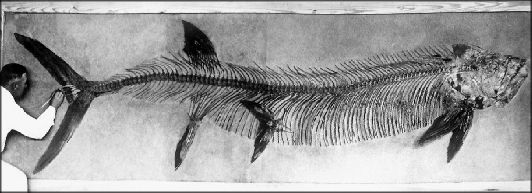

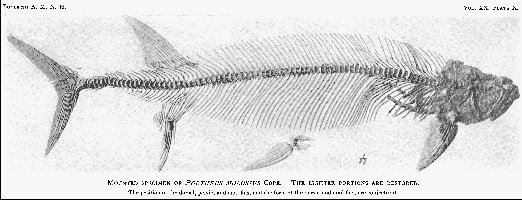

LEFT: Another specimen of Xiphactinus audax

(originally AMNH 32219; new number is AMNH FF 13102) collected

in 1901 by C.H. and G. F. Sternberg, and sold to the American Museum of Natural

History. (15 feet, 8 inches long; see Osborn 1904, Figure 1).

Note here that prominent paleontologists like

Osborn were largely responsible for continuing the usage of the junior

synonym (Portheus molossus) even though it had been corrected

earlier by O.P. Hay (1898), and A. Stewart (1898).

2006 PHOTO HERE |

|

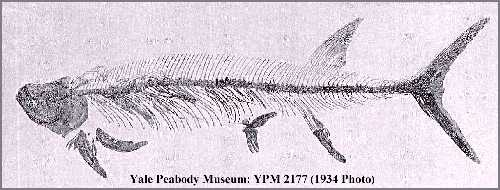

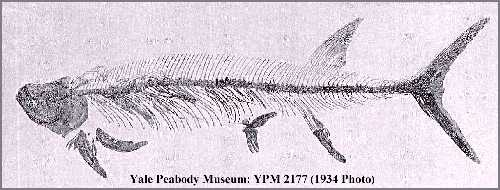

LEFT: Still another G. F. Sternberg specimen of Xiphactinus

audax. This one is in the Yale Peabody Museum collection. See Thorpe (1934). |

|

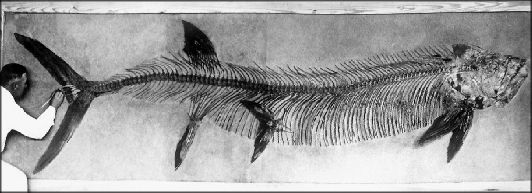

LEFT: This is the Xiphactinus audax specimen

(3.5 m) originally displayed in the museum at the Kansas State Teachers

College (now Fort Hays State University). It was collected by

G.F. Sternberg in 1926 on the south side of Twin Butte Creek in Logan

County. This specimen was sold to the University of Nebraska State Museum

in 1952 and then replaced with the current, much more famous "fish-within-a-fish" exhibit. RIGHT: A recent picture of

this same specimen (University of Nebraska State Museum: UNSM 1495).

Note that it also contains the remains of a last meal... another Gillicus. |

|

|

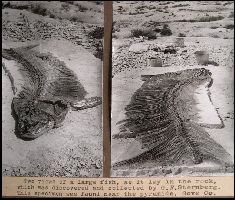

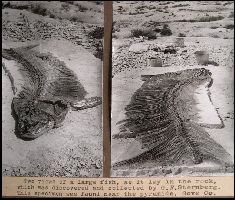

LEFT: Two views in the field of another Sternberg Xiphactinus collected

near Monument Rocks in Gove County - From the archives of the Fick Fossil and

History Museum, Oakley, Kansas. RIGHT: The "business end" of

15 foot long Xiphactinus audax collected and prepared by G. F. Sternberg in 1946

from Gove County, KS. You can see the caudal fin of a 7 foot long Gillicus just

behind the gills of the Xiphactinus. Although the smaller fish is partially

digested, the death of the larger fish probably occurred within hours of this last meal.

The specimen (DMNH 1667) is currently on exhibit in the Denver Museum of Science and Nature.

(See Rogers, 1991, p. 244-246) |

|

| Charles H. Sternberg (1922) reported that he had found a

remarkable skeleton of "Portheus." He noted that "it was preserved

from the pelvic fins to the end of the tail, and is the largest Portheus I have

seen. The spread of the tail fins is five feet. In 1918, my son Levi found a skull and

body part of a Portheus that is so near in size to this one that I have made a

composite skeleton of the two. It is sixteen feet long and will be, as I said, the

largest bony fish ever collected from the Cretaceous." |

|

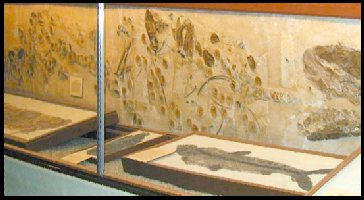

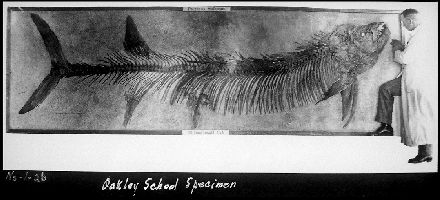

The Fick Fossil

and History Museum at Oakley Kansas has a large Xiphactinus audax

specimen that was found and prepared by G. F. Sternberg in 1926. It was originally

purchased by the town of Oakley for their public schools (Rogers, 1991). This specimen is

about 13.5 ft long. The fish is so large that I had to take four photographs to get

all of it into this composite photograph. |

|

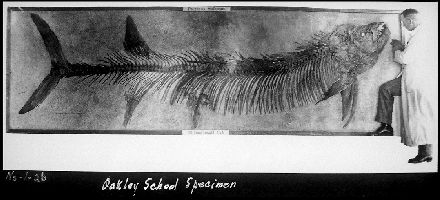

LEFT; G. F. Sternberg puts some final touches on the Xiphactinus

audax specimen he prepared for the Oakley School system. (Photo in the G.F. Sternberg

archives, Forsyth Library, Fort Hays State University) |

|

LEFT: G. F. Sternberg (at right, white lab coat) talks about this

specimen with students of the Oakley Public Schools about 1926 when it was acquired by the

the school for exhibit. (Photo in the G.F. Sternberg archives, Forsyth Library,

Fort Hays State University) |

|

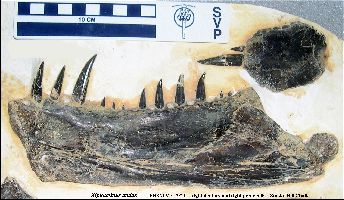

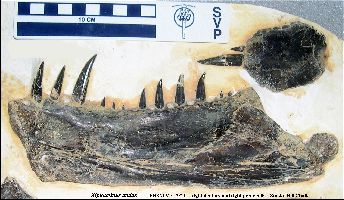

LEFT: Click the thumbnail for a better view of the business end of

the above specimen of Xiphactinus audax. The largest teeth are in the upper jaw

in two paired bones called 'premaxillae'. They are about three inches long and are conical

in shape for seizing prey. When the single large tooth was ready to be

replaced, there were two smaller teeth, growing one on reach side to take

over.

Unlike many large sharks of the period, Xiphactinus

was not capable of biting pieces off its prey and instead, swallowed them whole. This tended to get them in trouble, particularly when the prey

was large and struggling. A number of specimens have been found with large,

partially digested

fish still inside (most frequently Gillicus arcuatus, suggesting that the larger fish died while or immediately after

swallowing its prey.

|

|

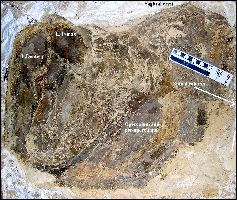

LEFT: The skull of another Xiphactinus audax in the Fick

Fossil and History Museum, Oakley, Kansas. Recently I found G. F. Sternberg's field

notes regarding the discovery, preparation, and disposition of this specimen:

"Oct.

28th, 1924 - Sp. 3 – Portheus molossus of Cope

Locality - 3/4 mile south of the locality of no. 2

Horizon – Cretaceous chalk

Collector – G. F. Sternberg

Description – Skull quite complete except for a small portion of the back part of the

gills. The left side of the skull is exposed and it is an individual which would be about

12 feet long. The bones are well preserved. Plaster is run in so as to appear the bottom

side. One section - size 32” x 35” x5” [Hand drawn picture here] As seen in

quarry of opposite side.

School collection no-1- includes this skull which when opened on right side proved to be

very fine." |

|

|

LEFT: The exhibit specimen of Xiphactinus audax in

the Hastings Museum, Hastings, Nebraska. Collected by G.F. Sternberg from

the Smoky Hill Chalk in southwestern Trego County, Kansas.

RIGHT: Another X. audax specimen in the collection of the University

of Nebraska State Museum. This one was collected by G.F. Sternberg

in 1931. |

|

|

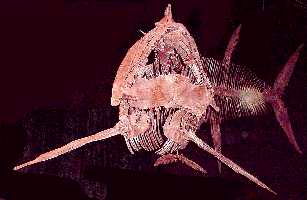

LEFT: The "exploded" skull of a relatively small Xiphactinus

(FHSM VP-2973) from the Smoky Hill Chalk collected by Marion and Orville Bonner in 1959.

This fish would have been only about 8 feet long when it died. Fish skulls often come

apart (explode) like this during decomposition. RIGHT: The very impressive lower

right dentary (medial view) and right premaxilla of the same specimen. |

|

|

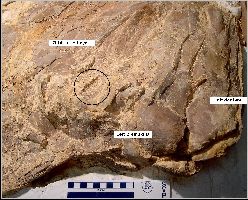

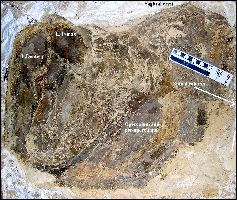

LEFT: Unusual preservation of a Xiphactinus audax skull

(FHSM VP-16440) in left lateral view. The specimen was collected in 2005 from the upper

chalk of western Gove County. The lower jaw is smashed backwards to the point that it is

nearly perpendicular to the vertebral column. This would suggest a high speed, head-first

impact with a sea bottom that was NOT soft mud. RIGHT: The same

specimen looking head on. Note that the large teeth in the lower jaws are pushed up

between the premaxillae and that the "facial" region of the skull, including the

orbit of the left eye has been crushed inward. HERE

IS a close-up of the front of the jaws. |

|

|

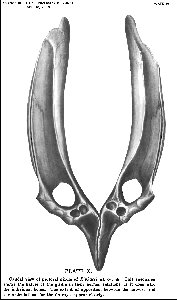

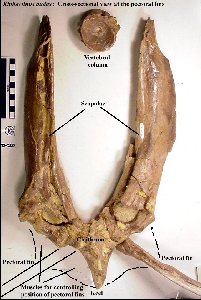

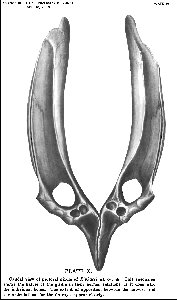

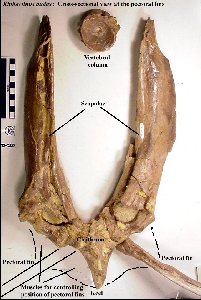

LEFT: The pectoral (shoulder) girdle of Xiphactinus

audax, shown in caudal (rear) view, adapted from McClung 1908 (Plate

X).

RIGHT: A similar girdle in my collection showing a cross-sectional

view of body of the fish at the shoulders and the relationship of the

vertebral column and the pectoral fins. |

|

|

LEFT and RIGHT: Two views of the vertebrae of Xiphactinus

audax. Large vertebrae like these are fairly common finds in the chalk. These

specimens are medium in size for Xiphactinus, about 5 cm (2 in.) in diameter and

3 cm. long, and probably came from a fish that was about 3 m (12 ft) in length. According

to Bardack (1965), Xiphactinus had an average of 85 vertebra. |

|

|

LEFT: In October, 2009, I chanced

upon the remains of a Xiphactinus in a road cut near Wilson Lake in Russell County,

Kansas. The specimen had originally been located by a friend of mine (Keith Ewell) about 5

years ago, so I cannot claim full credit for the discovery, but I had never known the exact location. The

ledge above my head is the Fencepost Limestone, used long ago for building stone and to

make stone posts like the one on the crest. There were very few trees in the

western part of Kansas at the

time it was settled (1870s-1890s). A dining room table-sized

chunk of this layer had fallen off and was standing vertically in the ditch to my right. I

wasn't very eager about tunneling in too far. Here I am using a hammer and

chisel to remove chalky layers of the Pfeifer Shale from above and below the fish vertebrae that were coming

straight out of the hillside. While the shale was fairly soft and easy to work, it was

difficult to remove because I kept sliding down the slope. (Dig pictures by Lee Garrison). RIGHT: These are the 3 vertebrae that I recovered from

the dig. The one that I discovered initially is on the left of the photo. The one at the

right was still articulated with at least one more vertebra. The remains come from a

medium sized Xiphactinus... probably 12-14 feet in length. Although Xiphactinus

is known to occur somewhat earlier than this discovery, this is the first specimen from

the Pfeifer Shale Member of the Greenhorn Formation. |

|

|

|

|

|

This Xiphactinus audax (ESU 1047) skull is on exhibit at

the Geology Museum at Emporia

State University, Emporia, Kansas. It had been bitten by a large Ginsu (Cretoxyrhina)

shark which left a calling card in the form for a broken tooth wedged in the third

vertebrae behind the skull. (See Shimada and Everhart, 2004) |

|

LEFT: This is a picture of a large Xiphactinus (BMNH P.

11125) in the British Museum of Natural History. The specimen was found by George

Sternberg and sold to the museum by Charles Sternberg. The picture was taken by the

parents of Charles Choguill, when they were in London in 1959-1960. According to Mr.

Choguill, this specimen and other Kansas fossils were no longer on exhibit when he visited

the BMNH in 1971. More recently (10/2007), Matt Friedman indicated that it was currently

on display in the Earth Gallery (the old Museum of Geology). RIGHT:,

George Sternberg uncovers the skull of another Xiphactinus (Photo provided by

Charles Choguill). |

|

The following is

a note written in regard to the above specimen (Sternberg, 1917, p. 11-12) and includes

Charles Sternberg's annotations of a story in the London Illustrated News:

"In 1911, I

sent George to western Kansas with a party to collect in the Chalk, and with wonderful results; for though I

had secured four skeletons of the famous Tarpon-like fish of the Cretaceous, named Portheus

molossus by Cope, he succeeded in finding the most complete skeleton known to science,

now mounted in the British Museum of Natural History, in London. Mr. Pycraft has pictured

it in the London Illustrated News for March 1, 1913. "The giant to which I refer

now" (he says) , "has been dead a very long while, a million years or so [over

5,000,000 - C. H. S.]. Its remains in a most extraordinary state of preservation, will be

found in the Geological Gallery. Measuring just fourteen feet in length, it must have

weighed between four and five hundred pounds [a thousand likely. - C. H. S.]. It was

obtained from the chalk of Kansas, and has quite a

remarkable history. It was found by Professor Sternberg, who has achieved a world-wide

fame for his discovery of fossil fish and his quite amazing skill in digging his finds

from the rock in which they are embedded. The specimen was found [by George F. Sternberg],

exposed at the surface of the ground, and was much the worse for wear and tear of wind and

rain and sun. But Professor Sternberg was equal to the occasion. For just as there are two

sides to every question, so there are two sides to every fossil. The resourceful

discoverer determined to get at the other side of this very stale fish; for the exposed

side was useless. Accordingly he covered it with a thick layer of plaster of Paris and

when this was set he proceeded to dig out the fossil from the bed of chalk. This

accomplished, he cut away the rock from the specimen, and eventually succeeded in exposing

the whole fish." [The underside at least.- C. H. S.]" The

specimen is described by Woodward 1913 - Click

here for Woodward's Plate XXIII. |

Click here

to see pictures of a dig

done by Triebold Paleontology on a very large (17 ft - 5.2 m) Xiphactinus that I

found in in 1996 in Gove County, KS. This specimen is on exhibit in the North American Museum of Ancient Life

in Lehi, Utah and elsewhere with the traveling "Savage Ancient Seas©"

exhibit. In September, 2003, I examined a beautiful, completely articulated specimen

that had been found by a private collector in Trego County. It would have been 17

feet long but was missing the front part of the skull.

| This specimen shown above is certainly the largest example of

this species ever mounted and may the the largest complete specimen ever found. In

her book on the Sternberg fossil hunters, Rogers (1991, p. 250) mentions that George

Sternberg had found specimens as long as seventeen feet (5.1 m), but they were not

complete. The remains also included stomach contents consisting of a partially digested Gillicus. |

|

Although we know that Xiphactinus grew to be very large as

adults, we know very little about them as juveniles. So far as I am aware, there are no

juvenile specimens of this species in the Sternberg, or University of Kansas collections.

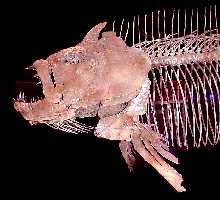

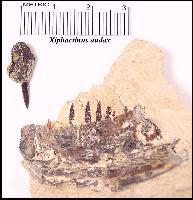

At LEFT and RIGHT are two views of a very small specimen of Xiphactinus audax

that I collected in 1999. It still needs to be prepared, but consists of one premaxilla

and both of the dentarys which are preserved together. When alive, this fish would have

only been about 30 cm (12 in) long. The single tooth in the premaxilla measures 8

mm, compared with 65+ mm in a large adult. Until these little guys grew up, they

were food for everything larger than they were... very few made it. |

|

|

This nearly complete Xiphactinus specimen was discovered

and prepared by Chuck Bonner. It is on exhibit in the Keystone Gallery, 25 miles south of Oakley in

Logan County, Kansas. This fish must have bloated after death and then was contorted into

this unusual shape. |

Click

here for Gary Staab's wonderful paleo-art on YouTube--- Creating a 3-D Xiphactinus

sculpture for the Hastings Museum, Hastings Nebraska.

Click here to see pictures of the 3-D mount of a

large Xiphactinus audax in the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History

at the University of Oklahoma.

Click

here for a webpage about the discovery of a much earlier Xiphactinus

(Cenomanian-Turonian) in Iowa.

|

LEFT: Head on view of the lower jaws between the

premaxillae of the first Xiphactinus audax reported from South

America (Venezuela).

RIGHT: Vertebrae of the same specimen. (Photos courtesy of Jorge Carrillo-Briceño)

See: Carrillo-Briceño, J., Alvarado-Ortega,

J. and Torres, C. 2012. Primer regristro de Xiphactinus

Leidy, 1870 (Teleostei, Ichthyodectiformes) en el Cretácico de América

del Sur (Formación La Luna, Venezuela). Revista Brazileira de

Paleontologia 15(3):327-335.

|

|

Other

Oceans of Kansas webpages on Late Cretaceous fish:

Field Guide to Sharks and Bony

Fish of the Smoky Hill Chalk

Sharks:

Kansas Shark Teeth

Cretoxyrhina and Squalicorax

Ptychodus

Chimaeroids

Bony Fish

Pycnodonts and Hadrodus

Plethodids:

Pentanogmius

Martinichthys

Thryptodus

Bonnerichthys

Protosphyraena

Enchodus

Cimolichthys

Pachyrhizodus

Saurodon and Saurocephalus

Xiphactinus

Suggested References:

Agassiz, J.L.R. 1833-1845. Recherches sur les Poissons Fossiles.

Neuchàtel and Soleure, Volume V, i-xii, 1-460l; Vol. V Atlas, Plates A-M,

1-64.

Bardack, D. 1965. Anatomy and evolution of Chirocentrid

fishes. University of Kansas Paleontological Contributions, Article 10, 88 pp. 2 pl.

Carrillo-Briceño,

J., Alvarado-Ortega, J. and Torres, C. 2012. Primer regristro de Xiphactinus

Leidy, 1870 (Teleostei, Ichthyodectiformes) en el Cretácico de América del Sur

(Formación La Luna, Venezuela). Revista Brazileira de Paleontologia

15(3):327-335.

Cope, E.D. 1871. On the fossil reptiles and fishes of the

Cretaceous rocks of Kansas. Art. 6, pp. 385-424 (no figs.) of Pt. 4, Special Reports, 4th

Ann. Rpt., U.S. Geol. Surv. Terr. (Hayden), 511 p. (Cope describes and names Portheus

molossus)

Cope, E.D. 1872a. On Kansas vertebrate fossils.

American Journal of Science, Series 3, 3(13):65.

Cope, E.D. 1872b. On the geology and paleontology of

the Cretaceous strata of Kansas. Preliminary Report of the United States Geological

Survey of Montana and Portions of the Adjacent Territories, Part III - Paleontology, pp.

318-349.

Cope, E.D. 1872c. [Sketch of an expedition in the

valley of the Smoky Hill River in Kansas]. Proc. Amer. Phil. Soc. 12(87):174-176.

Cope, E.D. 1872d. On the families of fishes of the Cretaceous

formation in Kansas. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 12(88):327-357.

Hay, O.P. 1898. Observations on the genus of fossil fishes called by

Professor Cope, Portheus, by Dr. Leidy, Xiphactinus. Zoological Bulletin 2(1):

25-54.

Hay, O.P. 1898. Observations on the genus of Cretaceous fishes called by

Professor Cope Portheus. Science, 7(175):646.

| Hay was quoted: "Professor O.P. Hay made some 'Observations on

the genus of Cretaceous Fishes, called by Professor Cope Portheus' discussing the

osteology of the genus at some length and particularly the skull, shoulder girdle and

vertebral column. He said that in many respects it resembled the Tarpon of our Southern

coasts, although possessing widely different teeth, and undoubtedly belonged to the

Isospondyli. The conclusion reached that Cope's Portheus is identical with the

earlier described genus Xiphactinus of Leidy. (Since the paper was read, the

author has learned that Professor Williston has reached the same conclusion.)" |

Leidy, J. 1856. Notices on remains of extinct vertebrated animals of New

Jersey, collected by Prof. Cook of the State Geological Survey under the Direction of Dr.

W. Kitchell. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 8:221.

(printed in 1857 - Naming of Polygonodon vetus, a sister species of Xiphactinus

audax, and Ischyrhiza mira Leidy)

Leidy, J.

1865. Cretaceous reptiles of the United States. Smithsonian

Contributions to Knowledge 14(6):1-135, pls. I-XX. (Three figures and a more detailed

description of the tooth of Polygonodon (Xiphactinus) vetus Leidy 1856)

<EM>

Leidy, J. 1870. [Remarks on ichthyodorulites and on

certain fossil Mammalia.]. Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Phil. 22:12-13. (The naming of Xiphactinus

audax from a fragment of a pectoral fin found

by Dr. George M. Sternberg (then an Army Surgeon serving in

Kansas) in the chalk of western Kansas --- this paper pre-dates Cope's 1872

description of Portheus molossus by over a year).

McClung, C.E. 1908. Ichthyological notes on the Kansas

Cretaceous, I. Kansas University Science Bulletin IV 235-246, pls. x-xiii, 10

text-figs.

Newton, E.T. 1877. On

the remains of Hypsodon, Portheus and Ichthyodectes from British

Cretaceous strata, with descriptions of a new species. Quarterly Journal

of the Geological Society of London

33:505-529, Pl. XXII.

Osborn, H.F. 1904. The great Cretaceous fish Portheus molossus Cope.

Bull. Mus. Nat. Hist. Vol. 20, Art. 31, pp. 377-381, pl. 10. [AMNH

32219]

Rogers, K., 1991. A dinosaur dynasty: The Sternberg fossil hunters,

Mountain Press Publishing Company, 288 pages.

Schwimmer, D.R., J.D. Stewart, and G.D. Williams, 1997. Xiphactinus

vetus and the distribution of Xiphactinus species in the eastern United

States. Journ. Vert. Paleo. 17(3):610-615.

Shimada, K. and M.J. Everhart.

2004. Shark-bitten Xiphactinus audax (Teleostei: Ichthyodectiformes) from the

Niobrara Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) of Kansas. The Mosasaur 7, p. 35-39.

Sternberg, C.H. 1917. Hunting Dinosaurs in the Badlands of the

Red Deer River, Alberta, Canada. Published by the author, San Diego, Calif., 261 pp.

Sternberg, C.H. 1922. Field work in Kansas and Texas. Kansas Academy

of Science, Transactions 30(2):339-348.

Stewart, A.

1898. A contribution to the knowledge of the ichthyic fauna of the

Kansas

Cretaceous.

Kansas

University Quarterly 7(1):22-29, pl. I, II. (Portheus Lowii sp.

nov., Daptinus broadheadi sp. nov., Saurocephalus dentatus

sp. nov., Protosphyraena bentonia sp. nov., and Protosphyraena sp. nov.)

Stewart, A.

1898. Individual variations in the genus Xiphactinus Leidy. Kansas

University Quarterly 7(3):115-119, pl. VII, VIII, IX, X. (Stewart has a short

note on page 115 acknowledging that Xiphactinus Leidy 1870 has priority

over Portheus Cope 1872)

.

| Stewart placed a short note on page 115 acknowledging that Xiphactinus

Leidy 1870 has priority over Portheus Cope 1872."Xiphactinus

audax Leidy (Proc. Acad. Sci. Phila., 1870, p. 12) has been shown to the a synonym of

Saurocephalus Cope (U.S. Geol. Surv., Wyoming, etc. 1872, p. 418). In a letter to Prof. Mudge, dated October 28, 1870, which

will shortly be published in the fourth volume of the Kansas University Geological Survey,

Cope refers it to Saurocephalus thaumas (Portheus thaumas Cope). After

carefully comparing the description and figure of the pectoral spine of X. audax

I was led to the same conclusion; and as the genus Portheus was not made known by

Cope until 1871 (Proc. Am. Phil. Soc., 1871, p. 173), according to the rules of

nonclamature Xiphactinus should have priority." |

Stewart, A.

1899. A preliminary description of the opercular and other cranial bones of Xiphactinus

Leidy.

Kansas

University Quarterly 8(1):19-21, pl. X-XI.

Stewart, A. 1899. Notice of three new Cretaceous fishes, with remarks on the

Saurodontidae Cope. Kansas University Quarterly 8(3):107-112. (Xiphactinus, Protosphyraena

gigas and Empo [Cimolichthys])

Stewart, A. 1900. Teleosts of the Upper Cretaceous. The

University Geological Survey of Kansas. Topeka 4:257-403, 6 figs., pls. 33-78.

Stovall, J.W. 1932. Xiphactinus audax, a fish from the Cretaceous of

Texas. University of Texas Bulletin No. 3201:87-92, 1 pl.

Thorpe, M.R. 1934. A new mounted specimen of Portheus molossus Cope.

American Journal of Science, 5th series, 28(164):121-126, 2 fig.

Walker, M.V. 1982. The Impossible Fossil. University Forum, Fort Hays State

University 26: 4pp.

Walker, M.V. 2006. The impossible fossil - Revisited. Kansas Academy of

Science, Transactions 109 (1/2), p. 87-96. (.pdf copies available on

request).

Woodward, A.S. 1913. On a new specimen of

the Cretaceous fish Portheus molossus, Cope. The Geological Magazine

10(12):529-531, Pl. XVIII.

For younger readers, see also:

Cutchins, J. and G. Johnston. 2001. Giant Predators of the Ancient Seas.

Pineapple Press, Inc. Sarasota, Fl. 64 pp.

Adapted from an image of Xiphactinus audax

at the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History.

Used with permission.

Photo by Judy Cutchins © 2001 - A 17 foot long

Xiphactinus in the Savage Ancient Seas exhibition, Fernbank Museum of Natural History,

Atlanta, GA.

BACK TO INDEX