|

A Field Guide to Fossils of the Smoky

Hill Chalk

Part 5: Coprolites, pearls, fossilized wood and

other remains.

Copyright © 2004-2012 by Mike Everhart

Page created 08/12/2004; Last Updated

09/09/2012

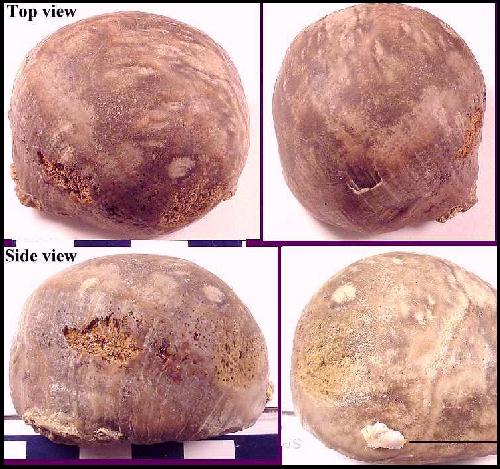

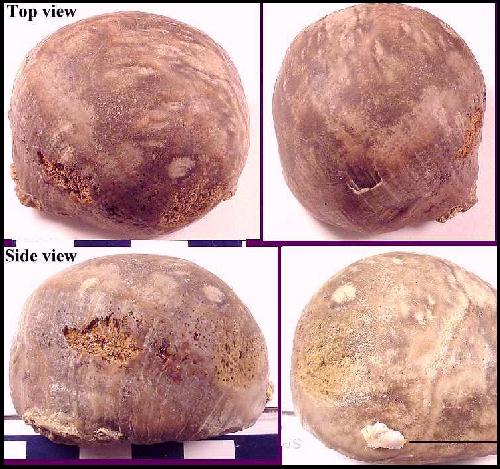

LEFT: Several views of a giant fossil

pearl found in the Smoky Hill Chalk, Gove County, Kansas (Click

to enlarge). The specimen is the size of half a golf ball. |

Continued from Part 4; Pteranodons,

Birds and Dinosaurs

F. OTHER KINDS OF SMOKY HILL CHALK FOSSILS:

1. Coprolites: The remains of feces / excreta are often found in the

chalk and sometimes contain well preserved vertebra and other fish bones. They are white

and chalky in appearance, and since they are composed largely of calcium phosphate, they

are more resistant to erosion than is the surrounding chalk. For more information, see my Coprolite webpage.

|

LEFT: A large shark or mosasaur coprolite found in the lower Smoky

Hill Chalk. The mass includes small pieces of bone and fish scales. RIGHT:

Shell coprolites - Small, compacted masses of oyster shell

fragments are found only in a limited zone in the lower 1/3 of the chalk. These appear to

be the coprolites from a fish or other predator that fed exclusively on oysters. At this

point, only the plethodid Martinichthys is a candidate. |

|

2. Fossilized Wood - Pieces of logs and branches floated out into the Western

Interior Sea where they became water logged and sank to the bottom.

Professor B. F. Mudge (1877, p. 283-284) was among the

first to note the presence of “an occasional fragment of fossilized wood.

… This wood was, in a few instances, bored before fossilization by some small animal.

This might have been done by the larva of an insect (a “borer”) when the tree

was living, or later by a teredo when the trunk floated in water. In either case it

shows that the Cretaceous vegetation was subject to the same enemies as that of the

present period. Some of this wood was in charred condition [carbonized] and would burn

freely. Other specimens were changed into almost pure silica, the cavities studded with

quartz. In one case a log, weighing about 500 pounds, had all conditions of the

transformation; a portion had the appearance of soft decayed wood, which crumbled in

handling, and other parts ringing like flint under a hammer. Occasionally specimens were

converted into chalcedony, but the annual growth of the wood distinctly remained. In a

single instance we detected the fibrous structure of the palm.”

The remains of a tree nearly 30 feet long were reported by Williston in 1897

from near Elkader, KS. Often flattened, the wood had become carbonized (or in some cases,

crystallized with calcium carbonate) and will burn poorly. Sometimes oysters and other

invertebrates attached themselves to the wood before it was covered by the bottom mud.

Most fossilized wood in the Smoky Hill Chalk is black in color but retains the grain of

the original wood. (NOTE

3. Pearls - Sometimes small round nodules are found attached to inoceramid

shells. They are the remains of pearls that were fossilized along with the clam shell. The

nacre or "mother of pearl" luster is not preserved in inoceramid

pearls. This is because the pearly, nacreous color associated with true

pearls is made up of a mineral called aragonite. In the Smoky Hill chalk, the aragonite is

not preserved. Inoceramid shells and pearls have lost the thin inner pearly aragonite

layer, and are solely composed of calcite. This also means that some kinds of shells, like

those of ammonites, were not preserved because they are composed entirely of aragonite. An

1940 article in the Hays Daily News noted that George Sternberg had donated 50 pearls from

the Smoky Hill Chalk to the Smithsonian Institution, and a scientific paper was published

on their occurrence (Brown, 1940).

|

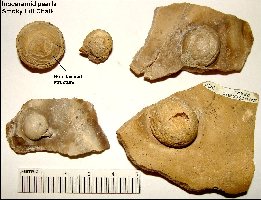

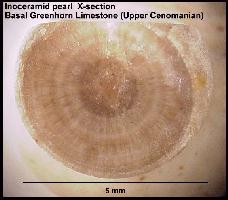

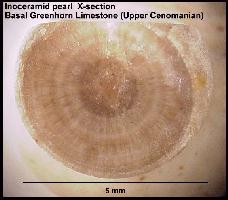

PEARLS FROM OTHER FORMATIONS

LEFT: Two small pearls (4-5 mm) from the base of the Lincoln Limestone Member

of the Greenhorn Limestone Formation (Upper Cenomanian) in Russell County, Kansas.

RIGHT: A cross section of the larger pearl shown at left showing. the

concentric layers. |

|

4. Borings: Many invertebrates that were living in the inland sea

are represented indirectly by casts, burrows and other evidence.

|

In some cases, the damage done

by cirripids as they bored into inoceramid shells is preserved while the actual animal is

not. In addition, the bottom muds of the inland sea may have been relatively low in oxygen

and may have not supported large numbers of smaller invertebrates. There is still much

work to be done in defining the somewhat limited invertebrate community of the inland sea.

|

5. Burrows - Burrow structures from worms and other invertebrates

were not generally preserved in the soft mud of the inland sea but can be found indirectly

in some chalk strata. Currently, it is believed that the harder layers of chalk are

evidence of thorough mixing (bioturbulation) by bottom dwelling organisms. It is likely

that much of the evidence was simply not preserved due to the consistency of the mud and

other, adverse chemical conditions as such lower levels of dissolved oxygen.

6. Bentonites - These are the remains of the ash (usually rust red

in color) from volcanic eruptions that fell on the surface of the ocean. There are more

than 200 bentonites in the Smoky Hill Chalk, each of which represents the eruption of a

fairly large volcano (larger than Mt. St. Helens in May of 1980) to the west of present

day Kansas. Some are an inch or more in thickness. Hattin (1982) used several of these

bentonites as part of his stratigraphic marker units in the chalk.

7. Iron concretions: Iron concretions are found through out the

Smoky Hill Chalk, but most often in the lower one-third. These concretions can form in

many shapes and sizes and are composed primarily of iron sulfide (jarosite). In some cases

they may form around bits of inoceramid shell or other debris. When freshly exposed, they

are often shiny and exhibit various metallic colors on the surface. They tend to degrade

fairly rapidly into splintery marcasite when exposed to moisture and often shatter or

become piles of rust-red debris.

|

LEFT: The smaller, oval forms

are referred to as "pop-rocks" locally. They may be relatively smooth or

have a definitely rough, crystalline surface. Small cubical pyrite nodules are found at

some levels.

RIGHT: A large concretion formed on an inoceramid shell

fragment, and roughly shaped like an animal. |

|

8. Silicified chalk - Variously referred to as Smoky Hill or Niobrara

jasper, silicified chalk was formed after eroded and exposed chalk was covered

by the sand of the Ogallala Formation. Silica leaching from the sand

permeated the chalk and hardened it.

"Smoky

Hill jasper, also known as Niobrara, Graham, or Republican River jasper,

is derived from the Smoky Hill Formation of the Central Plains. This formation

outcrops over a fairly widespread area across Kansas, Nebraska, Colorado, and

Wyoming, although the highest quality chert-bearing deposits are limited

primarily to locations from west-central Kansas to southwest Nebraska (see

Hattin 1982). Smoky Hill jasper is a highly siliceous material that varies in

color from caramel to dark brown, tan, black, white, green, yellow, and red.

These materials frequently occur as flat, tabular cobbles banded with several of

the above colors. Concentrations of quarries have been located in Graham, Trego,

and Gove counties in Kansas (see Banks 1990:96; Stein 1997)." Excerpt from

pages 183-184 of Brosowske, S.D. 2005. The evolution

of exchange in small-scale societies of the Southern High Plains. Unpublished

Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Oklahoma, 526 pp.

"Nodular, usually

stratiform masses of chert occur within the Smoky Hill Chalk at several places,

e.g., at Locality 23, at several places in Graham County (Prescott, 1955, p.

47), and at Norton (Logan, 1897a, p. 220). At locality 24, the nodules reach

thicknesses as great as 15 cm (0.5 ft). Smoky Hill chert is associated with

highly weathered chalk and occurs in the uppermost part of the exposure.

According to Frye and Leonard (1949, p. silicification took place at the same

time as the silicification in adjacent Ogallala (Miocene and Pliocene) beds."

Excerpted from Hattin, 1982, p. 19.

"In

a few places the chalk beds carry large amounts of chert which seem to be

interstratified with the chalk. This is well represented at Norton, along the

Prairie Dog Creek. Northwest of town about a mile the chert is quarried to a

considerable extent. Plate XXVIII shows this, and Plate XXIX shows the same

chert capping a chalk bluff at the old mill, Norton." Excerpted from Logan,

1897, p. 220-221, Volume II of the University Geological Survey of Kansas.

"From

the bluffs south of the Smoky a large quantity of clayey limestone has been

brought to fill the well. I found in these pieces of rock very good specimens of

common opal. They are white and look like porcelain, and were formed by the

infiltration of siliceous springs into the cretaceous strata; the magnesia

contained in the latter caused the silica to assume the opaline rather than the

agate or chalcedonic form." Excerpted from From

LeConte 1868, page 11.

For additional background information on Kansas geology, Smoky Hill Chalk,

marine fossils of the Late Cretaceous and paleontology in general, see my Late Cretaceous

Marine references about Marine reptiles and Fish and other fossils.

BACK TO INDEX