|

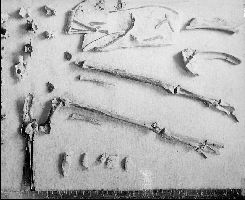

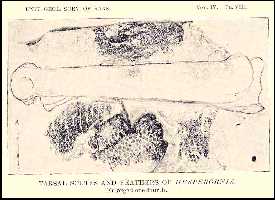

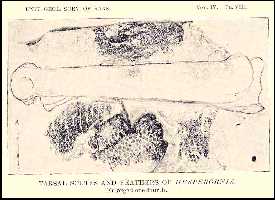

RIGHT: PLATE VIII.--- Photograph of scutes and feather impressions

of the tarsal region of Hesperornis specimen (KUVP 2287) published Williston in

the University Geological Survey of Kansas. Enlarged. S. W. Williston

(1898) wrote "A specimen now in the University Museum, collected by Mr. H. T.

Martin recently [1894, Graham County], is remarkable in showing the scuta of the

tarso-metatarsal region, together with the feathers. A photographic reproduction of this

part of the specimen is shown in Plate VIII. I have sketched in the tarso-metatarsal bone,

to show it's position. Indications of feathers are also seen on the back portion of the

head, and everywhere they appear to be more plumulaceous than the ordinary type of

feathers." (Williston, S. W., 1898. Birds. The University Geological Survey of

Kansas, Part 2, 4:43-53, pls.5-8.) See also Williston,

1898, On

the dermal covering of Hesperornis.

NOTE: KUVP 2287 was re-described by Larry Martin (1984) as the type specimen of

a new genus and species of hesperornithid bird, Parahesperornis alexi.

Martin, L.D.

1984. A new hesperornithid and the relationships of the Mesozoic birds. Kansas Academy of

Science, Transactions 87:141-150. |

|

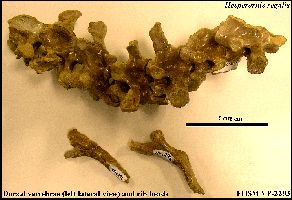

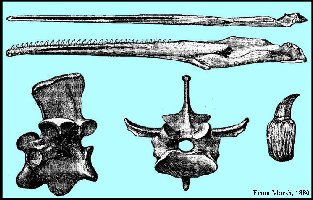

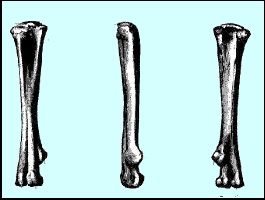

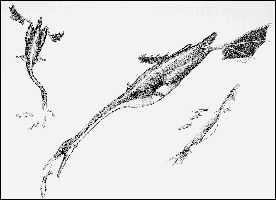

LEFT: The pelvis of the type of Parahesperornis alexi (KUVP

2287) in left lateral view. RIGHT: The femurs and tibiotarsi of KUVP

2287 |

|

|

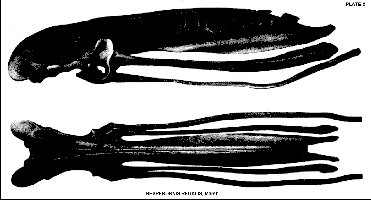

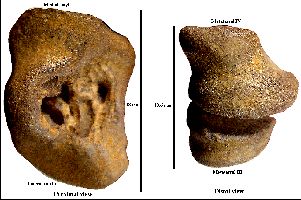

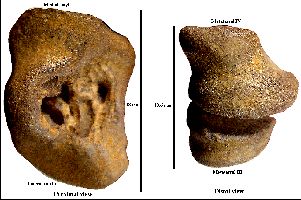

LEFT: The right tarsometatarsus of Parahesperornis sp.

(FHSM VP-17312) collected by Pete Bussen in the upper Smoky Hill Chalk (MU 22) of western

Logan County. This lower limb bone is about 9.7 cm in length and came from a medium-sized

swimming bird about the size of a modern cormorant. RIGHT: Proximal

and distal end views of the same specimen. The proximal end appears to have a possible

pathology that has destroyed the bone surface in the center of the joint.

See: Bell, A. and Everhart, M.J. 2009. A new

specimen of Parahesperornis (Aves: Hesperornithiformes) from the Smoky Hill Chalk

(Early Campanian) of western Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions

112(1/2):7-14. |

|

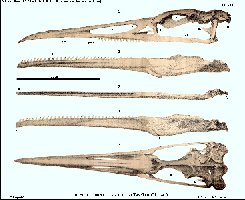

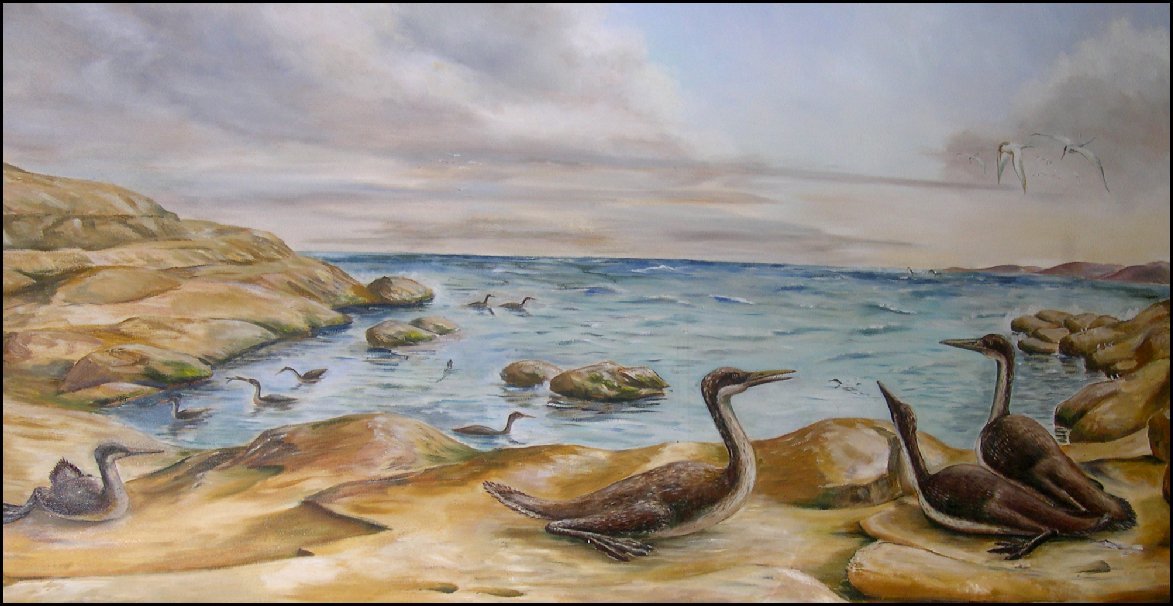

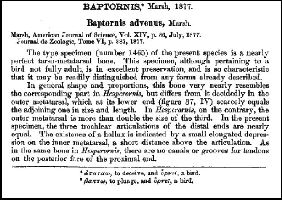

Baptornis varneri Martin and

Cordes-Person, 2007

| This new species of Baptornis was described by James

Martin and Amanda Cordes-Person from a specimen discovered some years ago by Dan Varner in the Pierre Shale of western South Dakota. Martin, J. E. and Cordes-Person, A. 2007. A new species

of the diving bird Baptornis (Ornithurae:

Hesperornithiformes) from the lower Pierre Shale Group (Upper Cretaceous) of southwestern

South Dakota. The Geological Society of America, Special Paper 427: 227-237.

ABSTRACT:

"Fossil

birds are relatively rare in Cretaceous deposits of the Northern Great Plains, so the

discovery of a large, new diving bird was unexpected. From marine deposits of the Niobrara

Formation in Kansas small diversity of birds was known, but until now the large diving

bird, Hesperornis was the only bird taxon

known from the Pierre Shale Group of South Dakota. The new discovery, a partial skeleton

of another diving bird, Baptornis, was secured

from the Sharon Springs Formation (lower middle Campanian) of the Pierre Shale Group in

Fall River County, South Dakota. The specimen is represented by vertebrae, pelvic

fragments, and lower leg elements that are similar to but much more robust than Baptornis advenus from the subjacent Niobrara

Formation. The new taxon is nearly twice the size of the Niobrara species, principally in

robustness rather than in length of elements. Overall, the specimen represents the first

occurrence of Baptornis from the Pierre Shale Group, represents a new species,

and indicates greater diversity of birds from the Pierre Shale Group than was previously

known."

Etymology: Named for Daniel

Varner who found the specimen, and for his notable contributions to paleontology in the

form of artistic renderings of extinct vertebrates. |

A very early Enaliornis-like bird from North America (The

oldest bird remains in the United States)

Enaliornis (Seeley, 1876) is a genus of hesperornithine birds from the

Early Cretaceous Cambridge Greensand of England. Two species have been described: Enaliornis

barretti and E. sedgwicki. Although remains are fragmentary and

incomplete, this is currently the oldest known hesperornithine. In June, 1979, two

fragments of a Enaliornis-like tarsometatarsus were surface collected from the

basal Lincoln Limestone Member of the Greenhorn Limestone in western Russell County,

Kansas. The limb bone would have come from a swimming bird somewhat smaller than Hesperornis

or Baptornis. The specimen was mentioned by Martin (1983) and Tokaryk, et al.

(1997) but was never fully described or figured. The English Enaliornis material

was re-described more recently by Galton and Martin (2002).

See: Everhart, M.J. and Bell, A. 2009. A hesperornithiform limb

bone from the basal Greenhorn Formation (Late Cretaceous; Middle Cenomanian) of north

central Kansas. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 28(3):952-956.

|

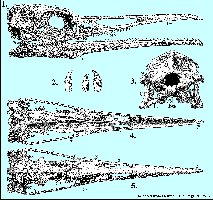

LEFT: Two views of the proximal and distal ends of the right

tarsometatarsus (FHSM VP-6318) of an Enaliornis-like bird from the basal

Greenhorn Limestone (Middle Cenomanian) of Kansas. This specimen represents the oldest

bird bone in Kansas and the United States, and is almost as old as the material

described from the Carrot River area in Saskatchewan, Canada by Tokaryk, et al., 1997, which is currently

the oldest bird fauna in North America. Their specimens also included an Enaliornis-like

bird. (Everhart and Bell, 2009) RIGHT: Four views of the distal end of

the specimen. The

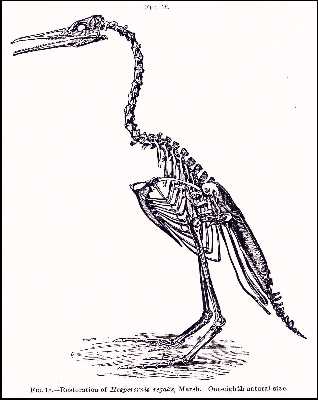

tarsometatarsus is a bone in the lower leg of birds. It is formed from

the fusion of several bones homologous to the ankle (tarsal) and foot (metatarsal) of

mammals. (See skeletal drawing of a Hesperornis leg HERE) |

|

References:

American

Ornithologists’ Union. 1910. Checklist of North American birds; 3rd edition. American

Ornithologists’ Union, New York, 430 pp.

Anonymous. 1891. Professor [D. W.] Thompson

on the systematic position of Hesperornis. Auk 8(3): 304-305.

Baird,

D. 1967. Age of fossil

birds from the Greensands of New Jersey. Auk 84(2): 260-262

Bell, A. and Everhart, M.J. 2009. A new

specimen of Parahesperornis (Aves: Hesperornithiformes) from the Smoky Hill Chalk

(Early Campanian) of western Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions

112(1/2):7-14.

Bell, A. and Everhart,

M.J. 2011. Remains of small ornithurine birds from a Late Cretaceous

(Cenomanian) microsite in

Russell County, north-central

Kansas. Kansas

Academy

of Science, Transactions 114(1-2):115-123.

Brodkorb, P. 1971. Origin and evolution of birds; pp. 19-55 in D. S. Farner and J. R. King (eds.), Avian Biology,

Volume 1, Academic Press, New York.

Bryant, L.J. 1983. Hesperornis in Alaska. PaleoBios 40:1-8.

Bühler, P., Martin, L.D. and Witmer, L.M. 1988. Cranial kinesis in the

Late Cretaceous birds Hesperornis and Parahesperornis. Auk 105 p.

111-122. (PDF of paper available on-line)

Chinsamy, A., Martin L.D. and Dodson, P. 1998. Bone

microstructure of the diving Hesperornis and the volant Ichthyornis from

the Niobrara Chalk of western Kansas. Cretaceous Research 19:225-235.

Cracraft, J. 1982. Phylogenetic relationships

and monophyly of Loons, Grebes, and Hesperornithiform birds, with comments on the early

history of birds. Systematic Zoology 31(1):35-56.

Cumbaa, S. L., Schröder-Adams, C.,

Day, R.G. and Phillips, A. 2006. Cenomanian bonebed faunas from the Northeastern margin,

Western Interior Seaway, Canada; pp. 139-155 in S. G. Lucas, and R. M. Sullivan (eds.), Late Cretaceous

vertebrates from the Western Interior. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science

Bulletin 35.

Elzanowski,

A. and Brett-Surman, M.K. 1995. Avian premaxilla and

tarsometatarsus from uppermost Cretaceous of Montana. Auk 112(3):762-767.

Everhart, M.J. 2005. Oceans of Kansas - A Natural History of the Western Interior

Sea. Indiana University Press, 322 pp.

Everhart, M.J. 2011. Rediscovery

of the Hesperornis regalis Marsh 1871 holotype locality indicates an

earlier stratigraphic occurrence.

Kansas

Academy

of Science, Transactions 114(1-2):59-68.

Everhart, M.J. and Bell, A. 2009. A hesperornithiform limb bone from

the basal Greenhorn Formation (Late Cretaceous; Middle Cenomanian) of north central

Kansas. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 28(3):952-956.

Fox,

R.C. 1974. A middle Campanian, nonmarine occurrence of the Cretaceous toothed

bird Hesperornis Marsh. Canadian

Journal of Earth Sciences 11:1335-1338.

Fürbringer, M. 1888.

Untersuchungen zur Morphologie und Systematik der Vögel, zugleich ein Beitrag zur

Anatomie der Stütz – und Bewegungsorgane; Verlag von Tl.J. Van Holkema, Amsterdam, 1751 p.

Galton, P.M. and

Martin, L.D. (2002): Enaliornis, an Early Cretaceous Hesperornithiform bird from

England, with comments on other Hesperornithiformes. pp. 317-338 in Chiappe, L.M.

and Witmer, L.M. (eds.): Mesozoic Birds: Above the Heads of Dinosaurs. University

of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London.

Gingerich, P.D. 1973. Skull of Hesperornis and early

evolution of birds. Nature 243:70-73.

Gingerich, P.D. 1975. Evolutionary significance of

the Mesozoic toothed birds. Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 27:23-34.

Gregory, J.T. 1951. Convergent evolution: The jaws of Hesperornis

and the mosasaurs. Evolution, 5:345-354.

Gregory, J.T. 1952. The jaws of the

Cretaceous toothed birds Ichthyornis and Hesperornis. Condor

54(2):73-88, 9 figs., 1 table.

Heilmann,

G. 1926. Origin of Birds. H.F. &

B. Witherby, London, 208 pp.

Hieronymus, T.L. and Witmer, L.M. 2010. Homology and

evolution of avian compound rhamphothecae. Auk 127(3):590-604.

Lane, H.H. 1946. A survey of the fossil vertebrates of Kansas,

Part IV, The Birds, Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 49(4):390-400.

Marsh, O.C. 1872. Discovery of a remarkable fossil bird. American Journal of

Science, Series 3, 3(13): 56-57.

Marsh, O.C. 1872. Preliminary description of Hesperornis regalis, with notices

of four other new species of Cretaceous birds. American Journal of Science 3(17):360-365.

Marsh, O.C. 1873. Fossil birds from the Cretaceous of North

America. American Journal of Science, Series 3, 5(27):229-231.

Marsh, O.C. 1875. On the Odontornithes, or birds with teeth.

American Journal of Science, Series 3, 10(59):403-408, pl. 9-10.

Marsh, O.C. 1876. Notice of new Odontornithes. The American

Journal of Science and Arts 11:509-511.

Marsh, O.C. 1877. Characters of the Odontornithes, with notice of

a new allied genus. American Journal of Science 14:85-87, 1 fig. (Naming and

description of Baptornis advenus)

Marsh, O.C. 1880. Odontornithes:

A monograph on the extinct toothed birds of North America. U.S. Geol. Expl. 40th

Parallel (King), vol. 7, xv + 201 p., 34 pl. (Synopsis of American Cretaceous birds,

appendix 191-199)

Marsh, O.C. 1883. Birds with Teeth. 3rd Annual Report of the

Secretary of the Interior, 3: 43-88. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

Marsh,

O.C. 1893. A new Cretaceous bird allied to Hesperornis.

American Journal of Science 45:81-82.

Martin, J.E. 1982. The occurrence of Hesperornis in the

late Cretaceous Niobrara Formation of South Dakota. Proceedings of the South Dakota

Academy of Science 71(95-97).

Martin, J.E. and Cordes-Person, A.

2007. A new species of the diving bird Baptornis (Ornithurae:

Hesperornithiformes) from the lower Pierre Shale Group (Upper Cretaceous) of southwestern

South Dakota. The Geological Society of America, Special Paper 427:227-237.

Martin, J. E. and Varner, D. W. 1992.

The occurrence of Hesperornis in the Late

Cretaceous Niobrara Formation of South Dakota. Proceedings of the South Dakota Academy of

Science 71:95-97.

Martin, J.E. and Varner, D. W. 1992.

The highest stratigraphic occurrence of the fossil bird Baptornis. Proceedings of the South Dakota Academy

of Science 71:167 (abstract).

Martin, L.D. 1980. Foot-propelled diving birds of the Mesozoic;

pp. 1237-1242 in Acta XVII Congress of International Ornithology.

Martin, L.D. 1983. The origin

and early radiation of birds. Chapter

9 (pp 291-338) in Bush, A. H. and

Clark, G. A., Jr. (eds.), Perspectives in

Ornithology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Martin, L.D. 1984. A new hesperornithid and the

relationships of the Mesozoic birds. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 87:141-150.

Martin, L.D.,

Kurochkin, E.N. and Tokaryk, T.T. 2012. A new evolutionary lineage of diving

birds from the Late Cretaceous of North America and Asia. Palaeoworld 21

(1):59–63.

Martin, L.D. and Bonner, O. 1977. An immature specimen of Baptornis

advenus from the Cretaceous of Kansas. The Auk 94:787-789.

Martin, L.D. and Stewart, J.D. 1996. Implantation and replacement of

bird teeth. Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 89:295-300.

Martin, L.D. and Tate, J., Jr. 1966. A bird with teeth. Museum

Notes, University of Nebraska State Museum, 29:1-2.

Martin, L.D. and Tate, J., Jr. 1976. The

skeleton of Baptornis advenus (Aves: Hesperornithiformes). Smithsonian

Contributions to Paleobiology 27:35-66.

Mudge, B.F. 1877. Annual Report of the Committee on

Geology, for the year ending November 1, 1876. Kansas Academy of Science,

Transactions, Ninth Annual Meeting, pp. 4-5. (discovery of Uintacrinus socialis

in Kansas, Pteranodon, sharks and birds.)

Rees,

J. and Lindgren,

J. 2005. Aquatic birds from the upper Cretaceous (Lower Campanian) of Sweden and

the biology and distribution of Hesperornithiforms. Palaeontology 48:1321-1329.

Reynaud, F. 2006. Hind limb and pelvis proportions of Hesperornis

regalis: A comparison with extant diving birds. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 26(3):115A.

Reynaud, F.N. 2006. Hind limb and

pelvis proportions of Hesperornis regalis:

A comparison with extant diving birds. Unpublished Masters Thesis, Fort Hays

State University, Hays, Kansas. 45 pp.

Seeley, H.G. 1876. On the British fossil Cretaceous birds. Quarterly Journal of the

Geologic Society of London 32:496-512.

Shufeldt, R.W. 1915. The fossil remains of a

species of Hesperornis found in Montana. Auk 32(3):290-284.

Shufeldt, R.W.

1915. Fossil Birds in the Marsh Collection of Yale University. Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and

Sciences 19:1-110, 15 pl.

Shufeldt,

R.W. 1915. On a restoration of the base of the cranium of Hesperornis

regalis. Bulletins of American

Paleontology 5:73-85, plates 1-2.

Snow, F.H. 1887. On the Discovery of a Fossil Bird Track

in the Dakota Sandstone. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 10:3-6

Sternberg, C.H. 1917. Hunting Dinosaurs in the Badlands of the

Red Deer River, Alberta, Canada. Published by the author, San Diego, Calif., 261 pp.

Thompson,

D’A. W. 1890. On the systematic

position

of Hesperornis. University

College, Dundee, Studies from the

Museum

of

Zoology

10:1-15, 17 figs.

Tokaryk, T.T., Cumbaa, S.L. and Storer, J.E. 1997.

Early Late Cretaceous birds from Saskatchewan, Canada: the oldest diverse avifauna known

from North America. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 17:172-176.

Townsend, C.W. 1909. The use of the wings and

feet by diving birds. Auk 26(3):234-248.

Walker, M.V. 1967. Revival of interest in the toothed birds of Kansas.

Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 70(1):60-66.

Williston, S.W. 1896. On the dermal covering of

Hesperornis. Kansas University Quarterly 5(1):53-54, pl. II.

Williston, S.W. 1898. Birds. The

University Geological Survey of Kansas, Part 2, 4:43-53, pls.5-8.

Williston, S.W. 1898. Bird tracks from the Dakota Cretaceous. The

University Geological Survey of Kansas, Part II, 4:50-53, Fig. 2. (Re-publication of

photograph originally published by Snow, 1887)