|

BIRDS.

BY S. W. WILLISTON.

REMAINS of birds always have been and

always will be the rarest of vertebrate fossils. From the habits of the great majority of

species, together with the lightness and buoyancy of their bodies in the water, it is very

evident that, even where they are abundant, they will not often fall into such positions

that they will be fossilized. Although, with our present evidence, they first made their

appearance in geological history as far back as the Jurassic formation, scarcely two score

of valid species have thus far been discovered from the Mesozoic, and all of those, with

one or two exceptions, are from the Upper Cretaceous formations.

The famous Archaeopteryx, from the Jurassic of

Solenhofen, the earliest bird known, has long been renowned for its strange mingling of

reptilian and avian characters. With the wings imperfectly developed, there were long

reptilian fingers with claws, adapted for seizing and grasping. The jaws were provided

with well-developed teeth, and the tail was elongated as in reptiles, each individual

vertebra provided with a pair of long feathers.

The famous footprints of the Connecticut Triassic

sandstone were, for a long time, supposed to have been made by birds. More recent

discoveries of the remarkable reptiles known as Dinosaurs have shown that it was not only

possible, but very probable, that all of them were made by these animals and none by

birds.

From the Lower Cretaceous no bird remains are yet

known. From the Upper Cretaceous, aside from the footprints noticed below, the only

remains yet known in America are from the Green Sand of New Jersey, the Niobrara

Cretaceous of Kansas,

(43)

44

University of Kansas Geological Survey.

and the Fox Hills Cretaceous of Wyoming. Laopteryx, the supposed bird

from the Jurassic of Wyoming, was founded upon very incomplete remains, and is, in all

probability, not a bird, but a small Dinosaurian reptile.

Twenty species of birds have been described from the

American Cretaceous, the larger number of which are from the Kansas Cretaceous. Not a few

of these are based upon very slight material, and it is not at all improbable that future

fortunate discoveries will unite some of these and at the same time add new forms to the

number already known.

Bird remains, in Kansas, are, as elsewhere, among the

rarest of the vertebrate fossils. One is likely to search weeks, and even months, without

finding a single bone, even fragmentary. Among the thousands of specimens of vertebrates

that have been collected in Kansas, not more than 175 of birds, of all kinds, have

hitherto been discovered.

BIRDS OF THE NIOBRARA CRETACEOUS.

The first specimens of birds known from Kansas were

obtained by the expedition of Professor Marsh in 1870. In the following year a much more

complete specimen of a Hesperornis was obtained by

another expedition in charge of Professor Marsh, and, in 1872, still other specimens. By

far the most important specimen of these early years, if not the most important of all

those succeeding, as well as the one from which the discovery of the dentition was made,

was one discovered by the late Professor Mudge, and sent by him to Professor Marsh. It was

found by him near Sugar Bowl Mound, in northwestern Kansas, in 1872, and was first

described by Marsh in October of that year under the name Ichthyornis

dispar.

An incident related to me by Professor Mudge in

connection with this specimen is of interest. He had been sending his vertebrate fossils

previously to Professor Cope for determination. Learning through Professor Dana that

Professor Marsh, who as a boy had been an acquaintance of Professor

Mudge, was interested in these fossils, he changed the address upon the box containing

the bird

WILLISTON.]

Birds.

45

specimen after he had made it ready to send to Professor Cope, and sent it

instead to Professor Marsh. Had Professor Cope received the box, he would have been the

first to make known to the world the discovery of "Birds with Teeth." (See Addenda to Part I.)

During the succeeding years, the large collections of

birds from this state were made for Professor Marsh by Mudge, Brous, Cooper, Guild, F. H.

Williston, and the writer. Other bird remains have been obtained by Sternberg and Martin.

In the University of Kansas museum there are portions of some twelve or more birds,

including one specimen of a Hesperornis, much the most complete and perfect of any

hitherto discovered. They apparently do not represent any new species or new forms, though

not all agreeing with those described by Marsh.

In the present paper it is not worth while entering

into any detailed description of these forms, inasmuch as the very complete and richly

illustrated monograph of Professor Marsh26 must remain indispensable to all

those who wish to obtain more complete information.

The following list includes all the known species of birds from the Kansas

Cretaceous, based upon fossil remains:

RATITĘ - Odontolcę.

Hesperornis.

Marsh, Amer. Journ. Sci., III, 56, Jan., 1872.

H. regalis Marsh, Amer. Journ. Sci., III, 56,1872.

This species is the best known and the most common of

all the species from the Kansas Cretaceous. Practically the complete skeleton is known.

See pl. VI.

H. crassipes Marsh, Amer. Journ. Sci. XI, 509, June, 1876 (Lestornis).

This species was discovered by Mr. G. P. Cooper, and

collected by the present writer from the yellow chalk of Plum creek, in Gove County,

Kansas. It is peculiarly characterized by the presence of a rugosity on the posterior

outer side of the tarso-metatarsal, above

____________________________

26. Odontornithes; a Monograph of the Extinct Toothed Birds of North

America. By Othniel Charles Marsh. New Haven and Washington, 1880.

46

University of Kansas Geological Survey.

its middle, as though for a spur. The specimen, which comprises a considerable

portion of the skeleton, was first described as the type of the genus Lestornis.

Marsh, later, thought that the roughening might be a sexual character.

H. gracilis Marsh, Amer. Journ. Sci., XI, 510,1876.

This species, of smaller size than the preceding, is

known from the nearly complete skeleton, according to Marsh, but has never been adequately

described.

Baptornis.

Marsh, Amer. Journ. Sci., XIV, 86, July, 1877.

B. advenus Marsh, Amer. Journ. Sci., I. c., 1877.

The type specimen, upon which this species and genus

were based, was collected by a member of the writer's party in the yellow chalk. The

generic difference is chiefly based upon the small size of the outer metatarsal.

CARINATĘ - Odontotormę.

Ichthyornis.

Marsh, Amer. Journ. Sci., IV, 344, Oct., 1872.

I. dispar Marsh, l. c., 1872.

The type specimen of this species was discovered, as

already explained, by Mudge in 1872. It is, perhaps, the most complete specimen of this

group that has ever been found, and the first of any known birds that showed the presence

of teeth in the jaws. The teeth were first described as belonging to a reptile, by Marsh,

in the Amer. Journ. Sci. for November, 1872, under the name Colonosaurus mudgei.

The species is at present known from nearly the complete skeleton.

I. agilis Marsh, Amer. Journ. Sci., v, 230, 1873 (Graculavus).

This species was based on very imperfect material

discovered by Marsh in 1872, and has never yet been adequately described or figured, so

that its determination, save by comparison with the type, will be more or less doubtful.

WILLISTON .]

Birds.

47

I. anceps Marsh, Amer. Journ. Sci., III, 364, May, 1872 (Graculavus).

The type specimen, from the North Fork of the Smoky

Hill river, has never been figured.

I. tener Marsh, Odontornithes, p. 198, 1880, pl. xxx, f. 8.

Discovered by Mr. E. W. Guild, on the Smoky Hill

river, in 1879.

I. validus Marsh, Odontornithes, p. 198, ff. 11, 14.

Discovered by myself on the Solomon river, in 1877.

I. victor Marsh, Amer. Journ. Sci.,

xi, 511, June, 1876.

The type specimen was discovered by Dr. H. A. Brous on

the Smoky Hill river. Forty other specimens are referred by the author to the same

species.

Apatornis.

Marsh, Amer. Journ. Sci. v, 162, Feb. 1872.

A. celer Marsh, Amer. Journ. Sci., v, 74, Jan. 1872 (Ichthyornis).

The type specimen was discovered by Marsh in 1872. A

more perfect specimen was found later by my brother, Mr. F. H. Williston, in 1877.

___________________

The systematic position of the toothed birds from

Kansas is by no means yet settled. All ornithologists are, however, agreed that they do

not form a separate group, and the name Odontornithes is in consequence generally

abandoned. The value of the teeth is subordinate; they do not in themselves justify a

separate subclass.

Hesperornis regalis, the best-known species of

the genus, was a bird measuring about six feet from point of bill to the tip of the feet

when outstretched, or standing about three feet high. It was an aquatic bird, covered with

soft feathers, wholly wingless, the rudimentary wing bones doubtless being enclosed under

the skin, and not at all effective in locomotion. The legs were strong and moderately

long; the neck long and flexible. The bill was long, and was provided with small but

effective conical teeth set in the jaw firmly. Those of the upper jaws were few in number

and set in the back part, while those of the mandibles formed a complete series.

48

University of Kansas Geological Survey.

The jaws were united in front by cartilage only, permitting considerable

mobility, which was doubtless very serviceable in swallowing their prey, which must have

consisted of fishes caught by diving. The bones of the body were solid throughout, not

hollow, as in almost all living birds. The sternum had no keel, as in the flying birds and

those descended from flying birds, but was as in the ostrich. The vertebrae and skeleton,

aside from the teeth, were not unlike those of modern birds, and, were the skull .yet

unknown, would be unhesitatingly referred to the subclass to which the ostrich, cassowary

and rhea belong. A specimen now in the University museum, collected by Mr. H. T. Martin

recently, is remarkable in showing the scuta of the tarso-metatarsal region, together with

the feathers. A photographic reproduction of this part of the specimen is shown in pl.

VIII. I have sketched in the tarso-metatarsal bone, to show its position. Indications of

feathers are also seen on the back portion of the head, and everywhere they appear to be

more plumulaceous than the ordinary type of feathers.

In pl. VI is shown the restoration of Hesperornis

regalis, after Marsh, together with figures of the jaws and of the teeth (pl. VII) It

may be added that the birds were of a low degree of intelligence, as proven by the small

size of the brain.

Ichthyornis was as different from Hesperornis

as a dove is from an ostrich. While in Hesperornis the wings were rudimentary and

the breast-bone without a keel, in Ichthyornis the wings were large and powerful

and the keel well developed. All the members of this group were small, none perhaps much

larger than a dove. The bones were hollow, as in most recent birds. The jaws had teeth,

like those of Hesperornis, and the birds doubtless fed upon fishes or other small

animals. The most peculiar character was, however, the structure of the vertebrae. In all

recent birds, as also in Hesperornis, the vertebrae have a peculiar articulation,

which permitted ample flexure in all directions. The articulation is what is called

reciprocal motion, or the saddle-shaped articulation, found, for instance, to a moderate

extent in the vertebrae of the human

WILLISTON.]

Birds.

49

neck. In this articulation the end of the centrum has the surface concave in

one direction and convex in the other, corresponding to similar but reversed concavity and

convexity in the adjacent surface of the contiguous vertebrae. In Ichthyornis this

peculiarity was almost wholly wanting, the two ends of the centrum being nearly alike and

gently concave in the middle. This concavity is not nearly so deep as in fish vertebrae,

but is nevertheless of that type, which suggested the generic name from ichthyos,

fish, and ornis, bird. In other respects Ichthyornis did not differ notably from

the common flying birds of the present time. Among recent birds the tern seems to approach

Ichthyornis most closely, due, doubtless, to similar modes of life. In pl. VII

will be seen the vertebrae and jaws of Ichthyornis, after Marsh.

Because Hesperornis was a swimming bird and Ichthyornis

a bird of powerful flight, skimming over the waters after the manner of the petrel, they

have been more subject to fossilization than the strictly land-inhabiting birds were.

Certainly there were many other species and genera of birds in existence at the time when

these lived, since the great difference between the two forms could not have been attained

without the development of many other forms. Of these, however, we have very few or no

remains. Whether all birds contemporary with them were toothed or not it is impossible to

say, but the probability is that they were.

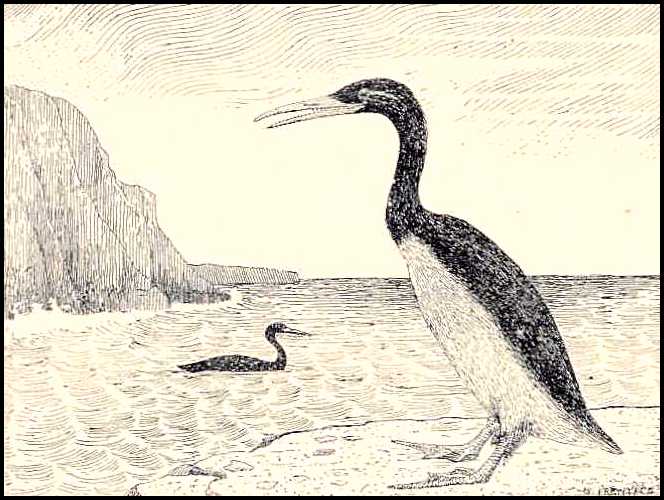

In pl. V a restoration of Hesperornis as in

life is shown, as drawn by Mr. Prentice, under my direction. Of course the coloration is

largely conjectural; it is that indicated by living birds of similar habits.

EXPLANATION OF PLATES.

PLATE V.-Life restoration of Hesperornis

regalis Marsh. Drawn by Sydney Prentice.

PLATE VI.-Skeleton of Hesperornis

regalis Marsh. After Marsh.

PLATE VII.-Figs. 1, 2, jaws of Ichthyornis

dispar Marsh, twice natural size; 3, 4, cervical vertebra of same, twice natural size;

5, 6, mandible of Hesperornis regalis Marsh, half natural size; 7, 8, vertebra of

same, natural size; 9, tooth of same, much enlarged. All after Marsh.

PLATE VIII.- Photograph of scutes and

feather impressions of the tarsal region of Hesperornis species, from a specimen in

the University of Kansas museum. Enlarged. |