The Denver Museum of Nature and Science

2001 Colorado Blvd., Denver, Colorado, 80205

Copyright © 2000-2009 by Mike Everhart

Page created 09/22/00; Updated 07/24/2009

|

The Denver Museum of Nature and Science 2001 Colorado Blvd., Denver, Colorado, 80205

Copyright © 2000-2009 by Mike Everhart Page created 09/22/00; Updated 07/24/2009 |

The Denver Museum of Nature and Science (formally the Denver Museum of Natural History) has a wonderful paleontology exhibit called "Prehistoric Journey. Colorado, like Kansas, was under a shallow inland seaway for many millions of years, but it also had a significant amount of time above water and thus has dinosaur remains, and other fossils of terrestrial origin. This page, however, will concentrate on the Cretaceous marine fossils on exhibit at the DMNS... to see the dinos and other interesting exhibits, you'll need to plan a visit to Denver.

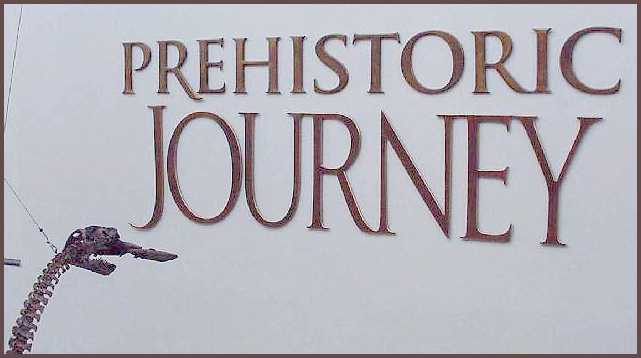

In my opinion, one of the more interesting areas in the Prehistoric Journey is what is referred to as the Kansas seashore.... the eastern edge of a vast ocean during the Permian Period (See remains of a Permian shark (Ctenacanthus) from Kansas HERE). Fossils from the Hamilton Quarry and Elmo Insect Beds of Kansas are well represented in the exhibit.

|

Part of the Kansas Seashore diorama, showing a stream valley leading down to the ocean. Fossils of many of these plants and animals are also on display in the Museum of Geology, Emporia State University, Emporia, KS. |

|

A reconstruction of a large Permian dragon fly (Meganeura, wingspread about 2 feet) in the Kansas Seashore diorama. More information about Kansas insect fossils is found on Roy Beckmeyer's webpage: Elmo, Kansas: The original Kansas/Oklahoma fossil insect lagerstatten. |

Besides the "Dancing T-rex" exhibit in the main entry, the Denver Museum has a number of dinosaur skeletons on display in the Prehistoric Journey, including a Stegosaurus family under attack by a hungry Allosaurus.

|

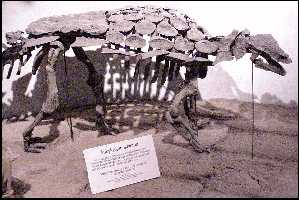

LEFT:I thought that the recently discovered throat armor on the mother Stegosaurus was rather

interesting. There were many other dinosaur skeletons in the Mesozoic exhibit. LEFT: Reconstructed skeleton of the Jurassic ankylosaur (Gargoyleosaurus parkpini) in the Denver Museum of Science and Nature. Note scutes dermal covering the head and upper body.) |

|

Invertebrates were major players in the ecosystem of the Western Interior Seaway. With the exception of the inoceramid clams, however, they are often poorly represented in the fossil record preserved in the Smoky Hill Chalk.

|

This is a large, well preserved specimen of Platyceramus platinus, the most commonly found inoceramid in the Smoky Hill Chalk. These bivalves grew to more than 4 feet across... giant clams by any standards. They are most closely related to modern oysters. |

|

A large slab of free swimming crinoids (Uintacrinus socialis) from the Mancos Shale in the Uinta Mountains near Grand Junction, CO. is included in the display. This species was discovered in 1870 during Professor O. C. Marsh's Yale Peabody Scientific Expedition to the West, and have been found in the Smoky Hill Chalk of Kansas. |

|

Crabs (Decapoda) were especially common along the Gulf Coast and the Mississippian Embayment. In some places in the Coon Creek Formation in western Tennessee they are literally preserved by the hundreds or thousands, possibly buried by a sediments from a major storm. This is a specimen of Avitelmessus grapsoideus from the Ripley Formation, Union County Mississippi (about 70 mya). Another specimen in the South Dakota School of Mines Museum of Geology is shown here. |

|

Nautiloids, ammonites, baculites, squid and other cephalopods were important links in the Late Cretaceous food chain. Their shells, however, generally dissolved before being fossilized. |

The museum has several well preserved late Cretaceous fish specimens on display.

|

A very nice specimen of Cimolichthys, a barracuda-sized predatory fish. |

|

This is Gillicus, an ichthyodectid fish most commonly found inside the belly of Xiphactinus. |

|

Pachyrhizodus minimus (about two feet long) is a small predatory fish. This species is often found preserved as a complete fish, including stomach contents and scales. |

|

Xiphactinus audax is one of the largest bony fishes known. It is estimated that this species reached lengths of more than 20 feet. They were certainly large enough to compete successfully with the marine reptiles and sharks of the late Cretaceous. They were capable of swallowing large prey, but often are found with the remains of their last meal still inside. Read George F. Sternberg's 1946 description of this specimen (DMNH 1667) below: |

PORTHEUS MOLOSSUS WITH A 7 FOOT GILLICUS IN ITS STOMACHHORIZON: Niobrara Cretaceous chalk. Sp.- 12746 LOCALITY: 14½ miles south of Buffalo Park, Gove County, Kansas. On D. Robertson ranch in the deep yellow chalk layers. Description: A very fine 15’ skeleton with a Gillicus specimen in its stomach which covers a distance of 7’ from the distal end tail which is still between the gills of the big fish and the extreme front of the lower jaws which lie between the pelvic fin and the anal fin. The Gillicus lies upside down in the stomach of the Portheus and the vertebrate column is somewhat scattered. The specimen is on three separate slabs or frames which measure 5’ 3” long by 56” tall or wide by 4” deep. All three fit together perfectly and where the bone is missing they have been painted in. This specimen is not fully prepared. When finished the missing parts will be restored in plaster. Collected and prepared by G. F. Sternberg in the fall of 1946. |

|

Only one mosasaur shows up in the Prehistoric Journey display.... a Platecarpus wall mount suspended over what would have been its major food items... Cretaceous fish. Their collection includes several other mosasaur specimens, including a large Tylosaurus skull.... and this example of what happens when a small Tylosaur gets eaten by a large shark..... teeth are totally dissolved and the surface of the bone is etched. ... see also: Shark Bites |

|

A large Protostega marine turtle swims overhead. A closer view of the skull is here. Other views of a cast of this specimen are shown on the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History page. |

|

Two mounts of Pteranodon skeletons are included in the exhibit, including the one shown here in a walking pose. |

|

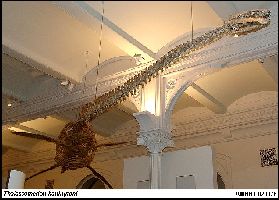

I've saved my favorite exhibit for last. The Denver Museum

has two casts of a large Cretaceous plesiosaur (elasmosaur) suspended gracefully overhead

in the main entryway of the museum. The original material (Thalassomedon

haningtoni Welles 1943: DMNH 1588) is in the museum's collection. Since

the museum has three levels accessible to the public, it is possible to see these two

spectacular specimens from above and from below at many different angles. Ken

Carpenter's excellent line drawings of the reconstructed skull, are also shown on my

Something about Plesiosaurs page. The original mount

of this skeleton (1950s-60s) is shown below:

....... so pardon me now as I over-indulge in a photographic essay about this wonderful exhibit. |

|

The two plesiosaurs are shown together, with one about to grab a bit of lunch while the other tries to steal a few bites for itself. DMNH 1588 is about 38 feet long and was found in the Graneros Shale of Baca County, Colorado. When living, it would have weighed several tons. The skull measures about 47 cm (19 inches) in length. |

|

A little closer view of the skull of this specimen. The small size and seizing teeth of plesiosaur skulls meant that they ate small prey; fish and soft bodied invertebrates. They also swallowed rocks (gastroliths) for use to either help digest their food or as ballast. Like many other elasmosaurs, this specimen was found with gastroliths. |

|

A view from directly under the skull, showing the interlocking teeth. The distance between the jaws at the back of the mouth is a practical limit to the size of the prey that this plesiosaur could swallow... in all cases, the prey was relatively small compared to the overall size of the plesiosaur. |

|

A view of the underside of one of the elasmosaur mounts..... showing the large, flat pelvic and pectoral girdles that are characteristic of all plesiosaurs. |

|

Plesiosaurs moved by using their large flat paddles as 'wings' or foils to fly underwater. Their ribs, gastralia (belly ribs) and plate-like pelvic and pectoral girdles made their bodies very stiff, providing the necessary rigidity to support this method of swimming. |

|

A view of the underside of the chest, showing the large, paired scapula and coracoid bones. |

|

A view of the underside of the hip area, showing the large, paired ischium and pubic bones. A picture of this specimen with the bones labeled is shown HERE. |

|

An overhead view of the shoulders of Thalassomedon haningtoni, showing the large paddles with their closely interlocking bones. |

|

An overhead view of the hips of the same specimen, showing how the vertebrae were connected to the pelvic bones. |

|

A overhead view showing the rear paddles and tail. |

|

A view of the right front paddle, showing the tightly interlocking bones of the lower arm (radius and ulna) and the wrist (Upper View / Lower View). Plesiosaurs exhibit a characteristic trait called 'hyperphlangy', meaning that there are many more bones in the 'fingers' than normal (humans, for instance, have 3 carpal bones in each finger; plesiosaurs may have 15 or more.) |

|

The crushed skull of DMNH-1588. Plesiosaurs are relatively rare as fossils and because of their small size and light construction, they are almost always crushed Slightly larger version (black and white). Compare this skull to a slightly larger one of the same species at the University of Nebraska State Museum: UNSM 50132 |

| Five views of the reconstructed skull and lower jaws of DMNH-1588 are shown below (Larger version in black and white): |

|

It is worth noting here that a cast of the Denver Thalassomedon is on display in the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York. Here are a few photos of the specimen as it is displayed overhead.

|

|

|

|

| LARGER VERSION HERE | LARGER VERSION HERE |

Click here for a primer on the anatomy of the plesiosaur skull.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thalassomedon haningtoni - "The Longest Neck in the Ocean".... a plesiosaur from Nebraska.

Other Marine Reptile References:Carpenter, Kenneth, 1999, Revision of North American Elasmosaurs from the Cretaceous of the Western Interior, Paludicola, 2(2):148-173

Cicimurri, D. J. and M. J. Everhart, 2001. An elasmosaur with stomach contents and gastroliths from the Pierre Shale (late Cretaceous) of Kansas. Kansas Acad. Sci. Trans 104(3-4):129-143.

Cope, E. D., 1868. Remarks on a new enaliosaurian, Elasmosaurus platyurus. Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Phil., 20:92-93. (for meeting of March 24, 1868) (First report of the plesiosaur, Elasmosaurus platyurus)

Cope, E. D., 1868. On a new large enaliosaur. Amer. Jour. Sci. ser. 2, 46(137):263-264. (Summary of Academy of Science article)

Cope, E. D., 1868. [On the structure of the vertebral column in Elasmosaurus]. Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Phil., 20:181. (for meeting of July 14, 1868)

Cope, E. D., 1869. (A resolution thanking Dr. Theophilus Turner for his donation of the skeleton of Elasmosaurus platyurus). Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Phil., 20:314. (Meeting of December 15, 1868)

Cope, E. D., 1870. On Elasmosaurus platyurus Cope. Amer. Jour. Sci., ser. 2, 50(148):140-141. (A response to Leidy's criticism)

Everhart, M. J. 2000, Gastroliths associated with plesiosaur remains in the Sharon Springs Member of the Pierre Shale (late Cretaceous), Western Kansas. Kansas Acad. Sci. Trans. 103(1-2):58-69.

Storrs, G. W., 1999, An examination of Plesiosauria (Diapsida: Sauropterygia) from the Niobrara Chalk (upper Cretaceous) of central North America, The University of Kansas Paleontological Contributions, (N. S.), No. 11, 15 pp.

Welles, S. P. 1943. Elasmosaurid plesiosaurs with a description of the new material from California and Colorado. University of California Memoirs 13:125-254. figs.1-37., pls.12-29.

Welles, S.P.1952. A review of the North American Cretaceous elasmosaurs. University of California Publications in Geological Sciences. 29:46-144. figs. 1-25.