Class

Osteichthyes (Bony Fish):

Bony

fish (including teleosts) were evolving rapidly at this time and beginning to produce the

variety of modern shapes and sizes that we see today. Some of the largest bony fish that

ever swam were in the Western Interior Sea during the Cretaceous Period and have left

abundant remains. Many times, however, only

the tail of the fish remains as evidence of the leftovers from a larger predator's

meal.

|

Most

of the remains that are found were from relatively large fish that must have been high in

the food chain. None of the smaller fish, which must have existed in great abundance to

support the other fish, mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, Pteranodons and

hesperornids are

well represented in the fossil record either because their skeletons were too small to be

preserved except under special conditions, and more likely, they were usually consumed by

larger predators.

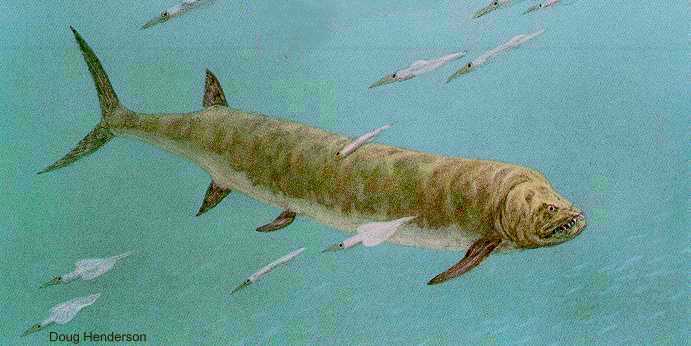

LEFT: Xiphactinus audax and

squid - Copyright © Doug Henderson; used with permission of Doug Henderson |

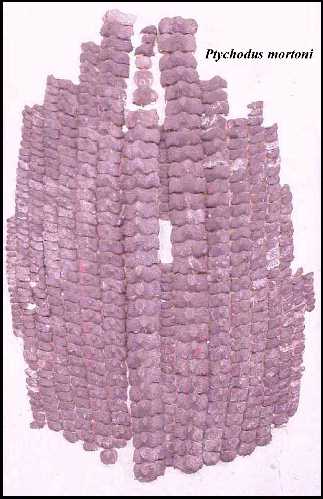

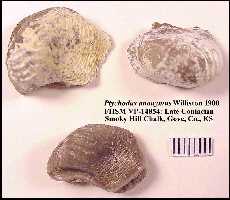

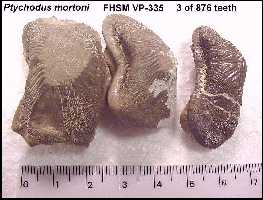

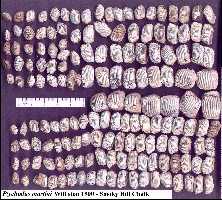

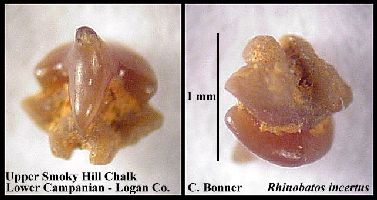

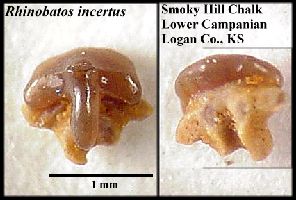

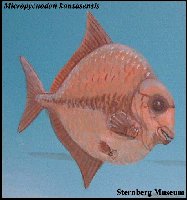

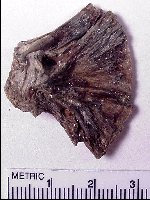

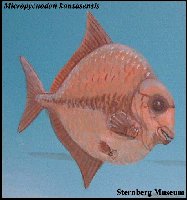

Micropycnodon kansasensis

Pycnodontids: Small

fishes, similar in many respects to the modern Parrot Fish, with crushing

teeth that look like small round pegs.

|

LEFT:

Apparently, this fish "nibbled" on the invertebrates that were attached to inoceramid shells at the bottom of the ocean,

although they are more commonly found and may have preferred much shallower water near

shore. Pycnodontids are found from the Early Cretaceous Kiowa Shale (Albian) through the

lower half of the Smoky Hill Chalk (Coniacian).

RIGHT:

A well preserved and fairly complete specimen of Micropycnodon kansasensis (KUVP

7030) in the collection of the University of Kansas. |

|

|

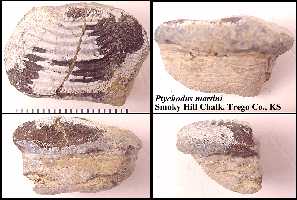

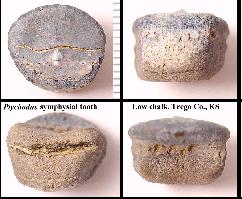

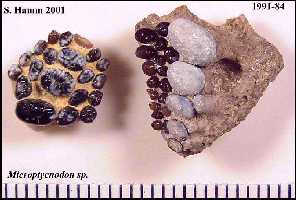

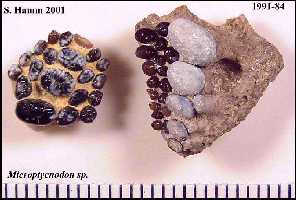

LEFT:

A photograph of two pycnodont jaw plates. The one at far left was found by Shawn Hamm; the

other was found by Pam Everhart in 1991. Two additional pictures of the right, lower jaw

of the 1991-84 pycnodontid (Micropycnodon) are here: (Photo 1; Photo

2)

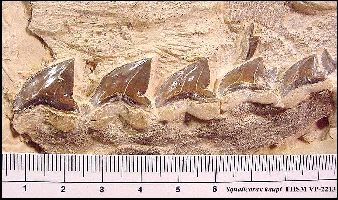

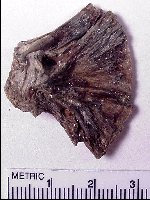

LEFT: A left

prearticular toothplate of a juvenile pycnodont

collected by Keith Ewell in 2004 from Trego County. The white color of some of the teeth

indicates oxidation of the enamel due to weathering. (Scale = mm) |

|

|

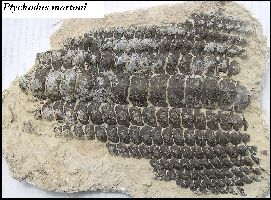

LEFT: A nearly complete specimen of Micropycnodon kansasensis

(KUVP 127042) in the collection of the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History

found by Laverne "Duffer" Mauck in southeastern Gove County in 1994 near

Hattin's Marker Unit 4. Head is to the left. RIGHT: A close up of the

spiky scales covering ventral side (keel) of this fish. The spines are made up of a enamel

like substance called ganoin which covers the scales and dermal bones of ganoid fish (Also

visible on the type and KUVP 7030) |

|

Lepisosteus sp. (Gars)

Gar

fish - A single, disarticulated specimen (KUVP 36243) was reported by Wiley and Stewart

(1977) from the lower chalk (Late Coniacian, zone of Protosphyraena perniciosa)

of Trego County, KS.

|

LEFT: FHSM VP-5114 -These large Lepisosteus sp. scales were

collected from the Kiowa Formation of Kiowa County and are Albian in age. Scales of Lepisosteus

sp. are also known from the Buildex Quarry in McPherson County, along with the teeth

of Lepidotes sp.

RIGHT:

Distinctive crowns of three teeth from the Lepisosteus sp. (KUVP 36243) remains described from Trego

County by Wiley and Stewart (1977). |

|

Division ?

Family Pachycormidae ?

Genus Protosphyraena Leidy, 1857

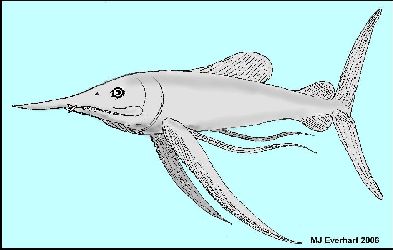

Protosphyraena:

A

large, fairly common fish that would have looked somewhat like a modern swordfish with a

sword-like beak and long, sickle shaped fins. They grew to large size. The pectoral fins

and shoulder bones are most frequently preserved as fossils of this genus, and in several

species the fins have a distinct saw toothed, leading edge. The genus includes: Protosphyraena

perniciosa (Cope, 1874); Protosphyraena nitida (Cope, 1872); Protosphyraena

tenuis Loomis, 1900; Protosphyraena gladius (Cope, 1873), and Protosphyraena

bentonianum (Stewart, 1898).

|

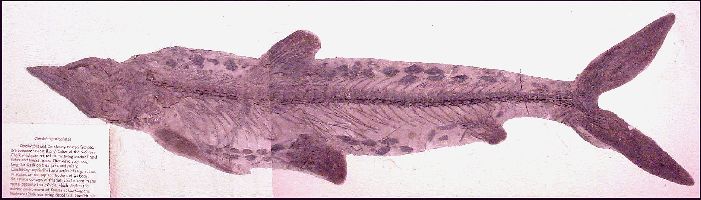

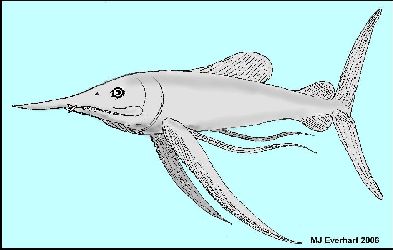

LEFT: This is the most

recent concept of what Protosphyraena may have looked like, based on the

first recovery of a nearly complete specimen. Although

lacking the anterior portion of the skull, it is the most complete specimen of Protosphyraena

ever found, and provides valuable information regarding the characteristics of this

fish. The fish is rather short for the size of it's long, saw-toothed pectoral fins and

large nearly vertical caudal fin. The pelvic fins are long and streamer-like, and emerge

just behind the pectoral fins.

RIGHT: The tail of a

Protosphyraena sp. specimen (KUVP 49419) in the University of Kansas

collection. Closer view HERE |

|

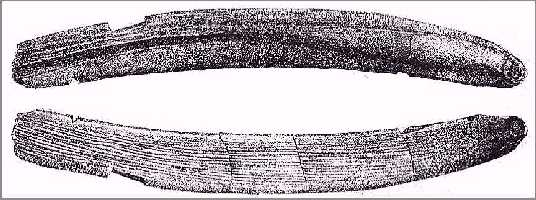

The

skull, with a sharp rostrum (nose) is also found preserved in the chalk and is readily

recognized by the flat, blade-like teeth. The anterior teeth in both jaws point

forward. The remaining skeleton was made up of poorly ossified bone and has not been found

preserved, except for the hypural bone of the caudal fin.

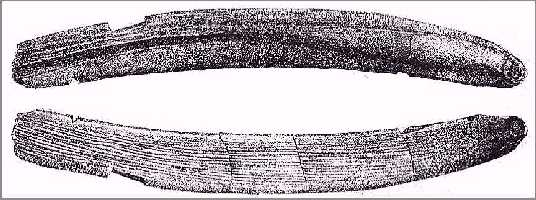

RIGHT:

The sharp snout of a Protosphyraena nitida skull (from Hay, 1903). These

relatively heavy pieces of bone are fairly common in the chalk. The heavy

scapulo-coracoid and pectoral fins are usually found preserved separately. |

|

Protosphyraena

perniciosa (Cope, 1874)

A large

predatory fish with long pectoral fins that had a sharp, serrated leading edge. Fins and

elements of the pectoral girdle are found most often. Found in lower 1/3 and extreme upper

portions of the chalk.

|

LEFT: A

complete set of Protosphyraena perniciosa fins (FHSM VP-80) that are on exhibit

in the Sternberg Museum, Hays, Kansas. These were collected in the lower Smoky Hill chalk

of Ellis County by George F. Sternberg. Each fin measures over 36 inches, and the complete

mount measures 77 inches with the scapulo-coracoid bones. (CLICK TO ENLARGE)

The

original name given to this fish by Cope in 1874 was Ichthyodectes perniciosus. He

did not recognize that it was in the genus Protosphyraena, named by Leidy in 1857. |

|

LEFT:

A complete skull of Protosphyraena sp. (FHSM VP-81) Probably P. perniciosa)

that is on exhibit in the Sternberg Museum, Hays, Kansas. This specimen was collected and

prepared by George F. Sternberg, and measures 15 inches from the base of the skull to the

tip of the rostrum. Note the forward facing teeth in both the upper and lower jaws. |

Protosphyraena

nitida (Cope, 1872)

|

LEFT:

Originally called Erisichthe nitida by Cope in 1873, Protosphyraena nitida was

a medium sized predatory fish with pectoral fins characterized by fine lines perpendicular

to the leading edge of the fin. Found in lower 1/3 of chalk. Mike

and Pam Everhart collected the only known complete

skull and fins of this fish. The specimen (LACM 129752) is now at the Los Angeles

County Museum of Natural History. |

|

LEFT: (EPC 1994-04) Protosphyraena nitida

fins do not have the jagged, saw-toothed edges found in P.

perniciosa. Instead they have fine grooves at right angles to the edge of the fin

(CLICK HERE FOR CLOSE-UP). |

|

LEFT: An associated partial skull and pectoral fin of

a very small (about 3 ft or 1 m) Protosphyraena nitida (EPC 2003-14) that I

collected in the lower chalk of southeastern Gove County (2003). This specimen is unusual

both for the small size and the association of a rostrum with a pectoral fin. The specimen

shows evidence of being scavenged by a shark, probably Squalicorax falcatus. |

Protosphyraena tenuis (Loomis, 1900)

A

medium sized predatory fish with sickle shaped fins characterized by a moderately serrated

leading edge. The serrations are not thickened in cross section as they are in P.

perniciosa. This species appears to replace P. perniciosa above the lower

1/3 of the chalk.

Bonnerichthys gladius (Cope, 1873)

|

LEFT: A very large but

relatively rare fish that is found in the upper 2/3 of the chalk. Pectoral fins are

massive in both length and thickness. This fish was recently determined not to a Protosphyraena

(swordfish). Little was known about the skull until recently, but now it appears to be a large filter feeder like Leedsichthys

from the Jurassic of England. It was redescribed and renamed by Friedman et al.

(2010). Protosphyraena gigas (Stewart, 1999) is a junior synonym of P.

gladius. |

Protosphyraena bentonianum

(Stewart, 1898)

This

species is a poorly known from the Lincoln Limestone Member of the Greenhorn Limestone

(Upper Cenomanian) that was described from a single specimen collected in Mitchell County

by S. W. Williston in 1897. More recently Keith Ewell and I have collected Protosphyraena teeth from below the contact

of the Dakota Sandstone and Graneros Shale in Russell County.

|

LEFT: Albin Stewart (1898, p. 27) described a new species of Protosphyraena

from the Lincoln Member (Upper Cenomanian) of the Greenhorn Limestone that had been found

by S. W. Williston in 1893 in southern Mitchell County. Stewart named the new

species Protosphyraena bentonianum. The specimen (KUVP 414) consists of a 20 cm (8

in) rostrum and several unidentifiable bone fragments. Although the type material

does not contain teeth, it is likely that the teeth in the photo at above left are also

from P. bentonianum. The inset is a close-up of the surface texture of the snout

which Stewart believed to be distinctive for the species. However, the same texture also

appears on Protosphyraena snouts from the Smoky Hill Chalk. Note

that the species name was first published as "bentonia" in 1898 by

Stewart, but then was noted to be a typographical error by Stewart (1900). |

|

LEFT: A recently collected (2005) specimen of Protosphyraena

perniciosa(?) / P. bentonianum from the Fort Hays Limestone of Jewell County

(private collection). Note the same surface texture on the snout as noted above. |

Subdivision Teleostei (teleost fish)

Family Ichthyodectidae

Ichthyodectids:

A

family of medium to very large, primitive bony fish; includes Gillicus, Ichthyodectes

and Xiphactinus.

|

LEFT:

All ichthyodectid fishes were covered with oval-shaped scales that were wider than they

were long. Sometimes these scales are preserved in the chalk, unassociated with other

vertebrate remains. The scale at left measures about 3.5 cm (1.5 in.) by 2 cm (the

anterior part of the scale is in the lower part of the picture). From the large size of

this scale, it is most likely from a Xiphactinus or an Ichthyodectes. |

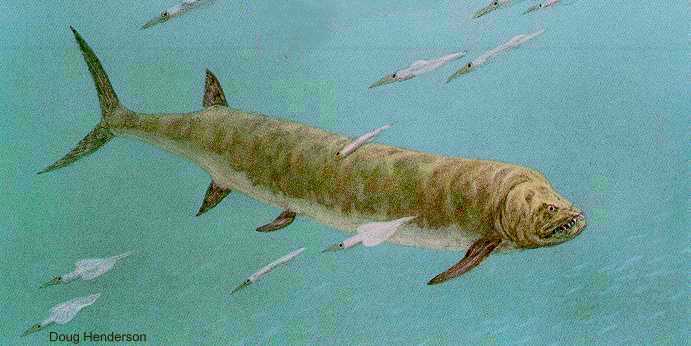

Xiphactinus audax:

Xiphactinus

was the largest bony fish of the Late Cretaceous, reaching lengths of nearly 20 feet.

These fish must have been the terror of the seas as far as anything smaller was concerned.

Nicknamed the "Bulldog" fish because of the upward thrust of it's lower jaw, the

fish would have been able to swallow very large prey, and this sometimes got them into

trouble.

RIGHT: Xiphactinus

audax and Gillicus |

|

A

number of complete specimens of Xiphactinus have been found with smaller

fish (Gillicus) inside. This could indicate that death was somehow caused by the

smaller fish but we will probably never know. The specimen shown above (FHSM VP-333 and

VP-334) is in the Sternberg Museum at Fort Hays State University and was collected by George F. Sternberg in 1952. Click on

the picture to see larger image. Xiphactinus page HERE.

|

While

the name Xiphactinus has been around since 1870, there has been considerable

confusion over which name is actually correct: Xiphactinus

audax (Leidy, 1870) or Portheus molossus (Cope,

1872). Joseph Leidy named the fish from a

fragment of a pectoral fin (USNM 52; at left) which was donated to the Smithsonian by Dr. George M. Sternberg a year before E. D. Cope gave the name of

Portheus molossus to a collection of several nearly complete specimens found near

Fort Wallace. Leidy won by virtue of being first to publish, but Cope's name was

more popular and is still in use in many collections of Cretaceous fish |

The

lower jaw of Xiphactinus audax (about 10 inches in length). The teeth of this

fish are very large and are generally unequal in size. |

|

The

vertebrae of Xiphactinus audax. These are the largest bony fish vertebrae found

in the Smoky Hill chalk and may reach 3 or more inches in diameter. The vertebrae

are spool-like, without ornamentation. This fish has no living relatives in today's ocean

but would probably have looked much like a modern tarpon.

Pictures

of two Xiphactinus audax vertebrae are HERE and

HERE (scale - mm)

|

|

The

pectoral fins of Xiphactinus were large and heavy, and were almost entirely made

of solid bone.

|

|

Ichthyodectes

ctenodon:

A

larger ichthyodectid fish with heavy jaws and small, equally sized teeth (see jaws below).

It grew to lengths of 8 to 10 feet and was a predator on smaller fish (see

Everhart, et. al., 2010). The complete

specimen (below) is a juvenile and is one of the smallest known reasonably

complete examples of this

species. (BELOW) Note that the bone on top of the head is the supraoccipital and was where

major muscles were attached.. it is NOT at horn or spike and

would not be visible in the

living fish.

|

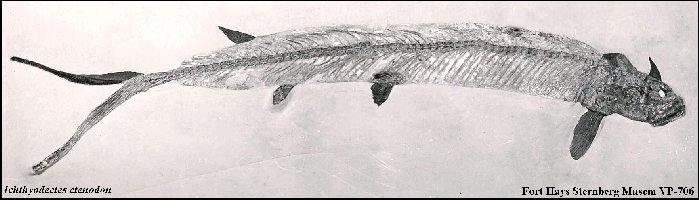

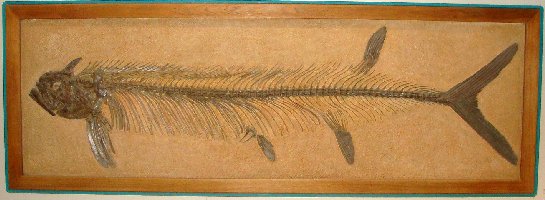

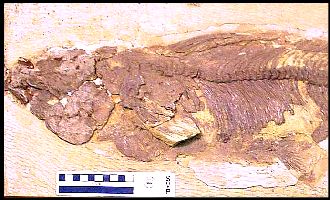

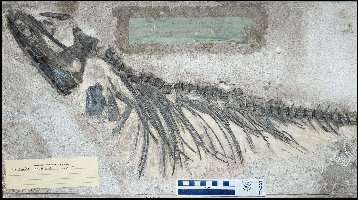

LEFT: USNM 12358 is one of the most complete

examples of Ichthyodectes ctenodon ever discovered. Only the tail is

restored. It was collected by George F. Sternberg and Myrl V. Walker in

1931 (GFS 4931). The dig was photographed and some of the photos are in

the archival collection of the Forsyth Library at Fort Hays State

University, Hays, Kansas. |

|

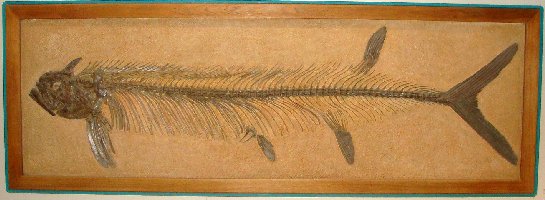

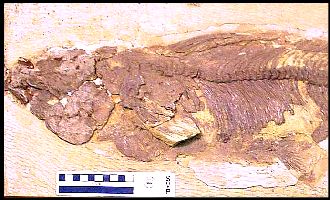

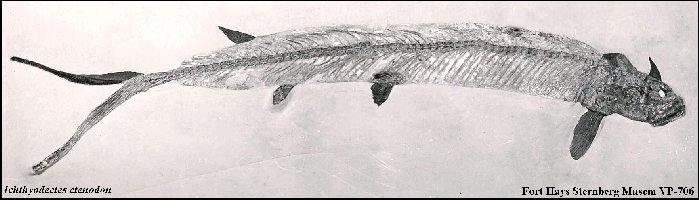

LEFT:

FHSM

VP-760 - About

49 inches long, collected by Marion Bonner in Logan County, KS - (Click here for skull).

Bardack (1965) notes that the fins and tail are restored and that

the "ventral

ends of pleural ribs are not preserved, giving

this fish an appearance of exaggerated length

in proportion to its depth." The spike on the head (supraoccipital) was added during preparation. (File photo, Sternberg

Museum of Natural History).

|

|

Vertebrae

are large, spool shaped, and without ornamentation. Ichthyodectes is very similar

to Gillicus in shape, but somewhat larger.

LEFT:

The skull of Ichthyodectes ctenodon in the Museum of Natural History at The

University of Kansas.

|

The

lower jaw of Ichthyodectes ctenodon showing the uniform size of the teeth. |

|

Gillicus

arcuatus

A

medium-sized, very elongate predatory fish with thin, blade like jaws having only a single row of very tiny teeth. These fish reached a

length of 5 or 6 feet and may have fed on plankton or other small food material filtered

from the water around them, but more likely ate smaller fish. Their remains are fairly

common. The genus was named by O. P. Hay (1898) in honor of Dr. Theodore Gill of the

National Museum (USNM - Smithsonian). It had originally been described in 1875 and

named Ichthyodectes arcuatus by E. D. Cope.

|

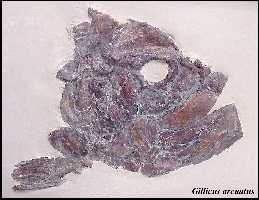

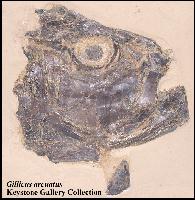

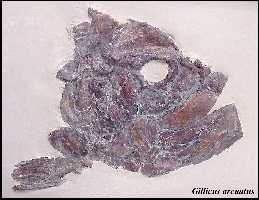

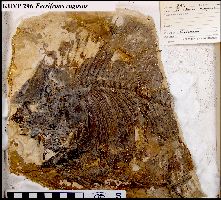

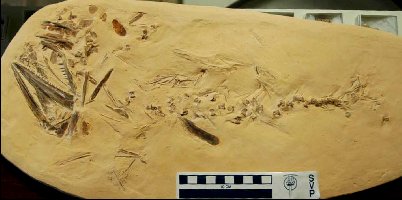

LEFT:

A fairly complete

specimen of Gillicus

arcuatus - FHSM

VP-420 - 1.3 m

|

|

|

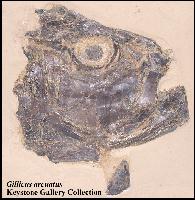

These

three Gillicus skulls were prepared by Chuck Bonner and are on exhibit in the Keystone Gallery, 25 miles south of Oakley, in

Logan County, Kansas. |

|

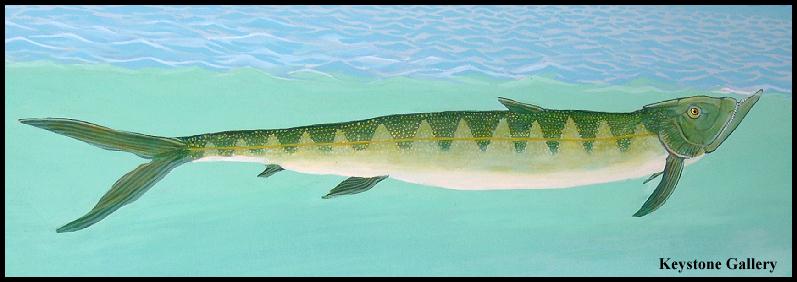

Saurocephalids (Saurodon leanus Hays, Saurocephalus

lanciformis Harlan and Prosaurodon pygmaeus

Loomis) - A medium sized predatory fish with a sword-like projection

from the lower jaw (pre-dentary). Teeth are small, equal-sized and blade shaped.

|

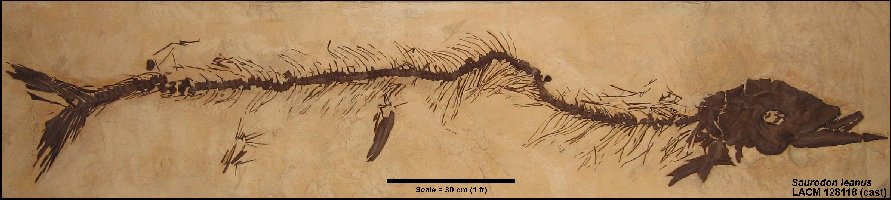

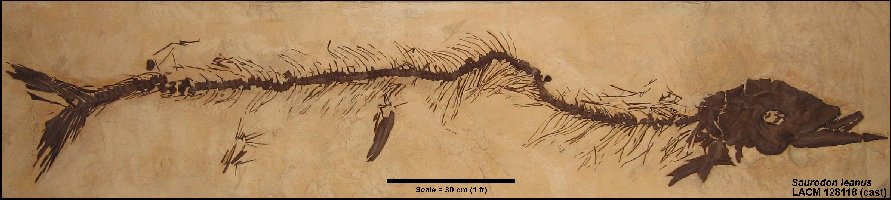

LEFT: One on the most on complete specimens of Saurodon

leanus known, this specimen was collected by Marion Bonner from

the Smoky Hill Chalk of Western Kansas and sold to the Los Angeles County

Museum of Natural History. This photos shows a cast of the specimen in the

Rocky Mountain Dinosaur Resource Center; a closer

view of the skull is here. (Photo by Anthony Maltese, used with

permission) |

RIGHT:

The skull of Saurodon leanus, showing the unusual extension of the lower jaw

(predentary).

The

type specimen of Saurocephalus lanciformis Harlan 1824 is the only surviving

fossil from the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1803-4. It was found in NW Iowa and is now

in the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (ANSP

5516).

See

also this historical paper: Harlan, R., 1824. On

a new fossil genus of the order Enalio sauri, (of Conybeare). Journal of the Academy

of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, Series 1, 3(pt. 2):331-337; pl. 12, figs. 1-5. |

|

|

LEFT: The skull of Saurodon leanus Hays in the exhibits of the

Sternberg Museum of Natural History. (FHSM VP-168) |

|

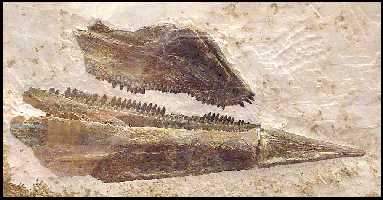

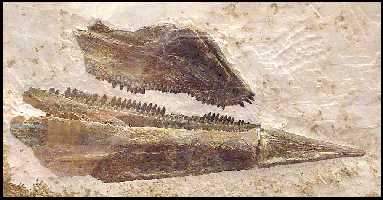

LEFT:

The lower jaws / predentary, and partial right upper jaw / premaxilla of Saurodon

leanus (V-968) from the Fryxell

Geology Museum at Augustana College in Rock Island, Illinois. The

partial lower jaw is 20.7 cm in length. This specimen was

collected in 1941 by George Sternberg (GFS 10841) from the Smoky Hill Chalk

in western Gove County along the Smoky Hill River. Sternberg

originally sold the specimen to the University of California Museum of

Paleontology where it was curated as UCMP 57555. It was subsequently

obtained by the Fryxell Museum in an exchange of specimens (Pers. comm.,

2012, Susan Kornreich Wolf, Associate Curator,

Fryxell

Geology

Museum

). Here is

a more recent photo. As

described by George F. Sternberg: "#10841 Saurodon: The left

upper jaw with premaxillae in place. Both [of] the lower jaws with

predentary in place. Total length 8 1/4". The inside of the upper

jaws shows with both lowers in place. A few teeth are missing. Size of the

slab 11" X 6". Bone and teeth good. A few teeth missing.

Unprepared." |

|

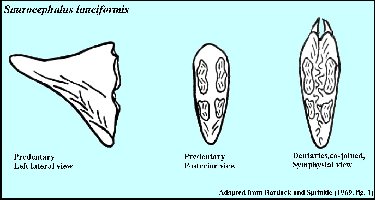

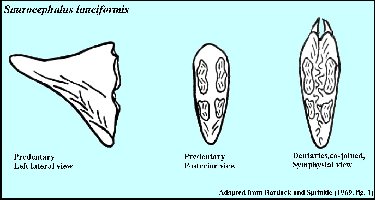

LEFT: The predentary of Saurocephalus lanciformis,

adapted from Bardack and Sprinkle (1969, fig.1), based on an unnumbered

specimen in the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University. Note

that the predentary is much smaller and shorter in S. lanciformis

than in S. leanus.

RIGHT: Two S. lanciformis predentarys from the upper chalk

(Early Campanian), Logan County, Kansas, in left lateral and posterior

view. |

|

Plethodids:

Bananogmius evolutus (Cope)

Pentanogmius

evolutus (Cope) is one a diverse family of plethodids from the Late

Cretaceous of Kansas. The remains of plethodids are a fairly common in the Smoky

Hill Chalk. The family Plethodidae includes the genera: Pentanogmius

(originally "Anogmius" evolutus,

then Bananogmius),

Niobrara, Zanclites,

Luxilites, Syntegmodus,

Bananogmius, Martinichthys,

Thryptodus, and Plethodus.

The species "Bananogmius evolutus"

was recently removed from the genus Bananogmius and renamed Pentanogmius

evolutus by Taverne).

A medium sized fish (4 to

6 feet) with a narrow, but deep body

(like an Angel Fish) and jaws that had small,

comb-like teeth. Most of the skeleton was bone and preserved well. A commonly found

fossil is the palatine bone from the roof of the mouth. These have a pebbled surface that

served as the base for hundreds of small, sharp teeth.

|

Pentanogmius

was a medium to large sized fish (4 to 6+ feet) with a

narrow, but deep body (somewhat like a modern Angel fish) and jaws

that had small,

comb-like teeth. Most of the skeleton was bone and preserves well. A

commonly found fossil is the palatine bone from the roof of the mouth.

These have a pebbled surface that served as the base for hundreds of

small, sharp teeth.

E.D.

Cope originally named the genus "Anogmius" in 1877, but

that genus name had already been used (e.g. pre-occupied).

LEFT:

DMNS 57159 - A large and nearly complete Pentanogmius evolutus

(Cope) discovered by Chuck Bonner in the Smoky Hill Chalk of western

Kansas. The tail is reconstructed.

|

|

LEFT:

The exhibit specimen of Bananogmius (Pentanogmius) evolutus (FHSM

VP-2182) in the collection of the Sternberg Museum. Although not fully displayed in this

photograph of the reconstruction, the fish had a large, sail-like dorsal fin. |

|

LEFT:

Bananogmius (Pentanogmius) evolutus FHSM VP-2117)

collected by Marion Bonner in the Sternberg Museum of Natural History. The caudal fin (tail) is

reconstructed. A close up view of the skull is HERE. A view of the teeth on the lower jaw

of another specimen is HERE. |

|

LEFT: The skull of a large Bananogmius

(Pentanogmius) evolutus - KUVP 27815 in left lateral view collected from the

Pierre Shale in 1971 by the Orville Bonner party. RIGHT: The type specimen of Bananogmius ellisensis, preserved

uncrushed in an ironstone concretion from the Blue Hill Shale Member of the Carlile Shale,

Ellis County, Kansas (Middle Turonian in age). |

|

Thryptodus:

Complete

skulls of this strange, "battering-ram" fish are found rarely in the chalk, but

mostly, only the rostrum at the tip of the skull survives. Unfortunately, the type

specimen from the Kansas Chalk was destroyed in Germany during World War II.

|

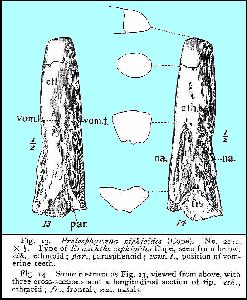

LEFT:

The skull of Thryptodus was heavily built, with a rostrum (the ethmoid bone) that

is very massive. Another unusual feature is the flat surface at the anterior

end. How was this fish using its head? Click HERE

for a drawing of the skull of Thryptodus zitteli (from Loomis 1900). In Kansas,

these fish are only found in the lower 1/4 of the Smoky Hill Chalk and apparently become

extinct by the end of the Coniacian stage (about 86 mya). |

Martinichthys:

These

fish are somewhat mysterious in that they are only known to occur in Kansas, and only in a

relatively narrow section of the chalk. There are only two partial skulls of these fish

known and few vertebrae. One of them (KUVP 497) is shown

here.

|

LEFT: The type specimen of Martinichthys brevis

(KUVP 497) in the collection of the Natural History Museum of The University of Kansas,

and the only known, reasonably complete skull of Martinichthys. This is the only

known publication of a picture of this skull since it was first described and published

with photographs in 1926 by C. E. McClung (A drawing of this skull was published by

Taverne, 2000). Note that there are five vertebrae associated with the skull.

(Scale = cm) |

|

LEFT: The skull of the type specimens of Martinichthys

ziphioides (KUVP 498) in the collection of the Natural History Museum of The

University of Kansas. There are 21 vertebrae associated with this specimen. (Scale = cm) |

|

These

fish are usually represented in the fossil record only by a hard, blunt nose or rostrum.

These rostra are often worn off at an angle as if the fish was using it to hammer at a

hard substrate such as shells. The teeth are very small and comb-like in appearance. These

fish only occur in a narrow zone in the lower 1/3 of the chalk. They are relatively rare

(found only in Kansas) and there are less than 85 examples in collections. Most of the

specimens are in the collections of the Sternberg Museum and the Museum of Natural History

at the University of Kansas.

LEFT:

FHSM VP-15567 - A recently discovered (2003), well-preserved Martinichthys brevis

rostrum from the lower Smoky Hill Chalk of Gove County, KS. |

Other

Plethodids:

Relatively

rare and unknown. These specimens are in the KU Museum of

Natural History:

|

LEFT: The skull of Ferrifrons rugosus

Jordan 1924 (KUVP 296), the anterior portion of a complete specimen (damaged). It was

almost 75 years later that this species was determined to be a plethodid (see Arratia and

Chorn. 1998. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 18(2): 301-314. The original specimen is

24.5 inches long and was collected by H.T. Martin about 4 miles northeast of Gove, in Gove

County, KS. |

|

LEFT:

Niobrara encarsia Jordon 1924 - This specimen was collected by H.T. Martin in

Trego County. Another view of the type specimen

(KUVP 179). |

|

LEFT:

Zanclites xenurus Jordon 1924 - This specimen was collected by H.T. Martin about 1/2

mile northeast of Gove, Gove County, KS. Another

view of the type specimen (KUVP 52) |

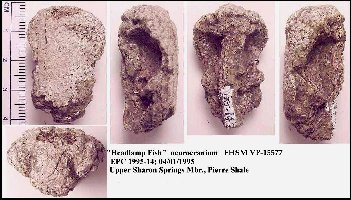

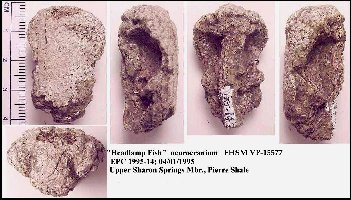

Aethocephalichthys

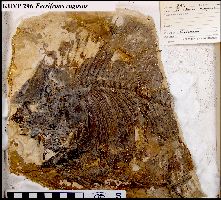

hyainarhinos

Headlamp

Fish: A very unusual fish that is known only from the highly fused neurocrania that

have been found in Mississippi, Kansas, South Dakota and New Zealand.

|

LEFT: The specimen shown at left is from the Pierre

Shale. It was found by Pam Everhart in 1995, and donated to the Sternberg

Museum in 2004 (FHSM VP-15577). However, at least one specimen is known from the Smoky

Hill Chalk in Gove County and is in the collection of the University of Kansas.

RIGHT:

FHSM VP-16466 is a new specimen collected in the Smoky Hill Chalk of Gove County, Kansas.

For

more information, see: Fielitz, C., Stewart, J.D. and Wiffen, J. 1999. Aethocephalichthys

hyainarhinos gen. et sp. nov., a new and enigmatic Late Cretaceous actinopterygian

from North America and New Zealand, pp. 95-106, 7 fig., in Arrantia, G. and Shultze, H-P.

(eds.), Mesozoic Fishes 2 - Systematics and Fossil Record. |

|

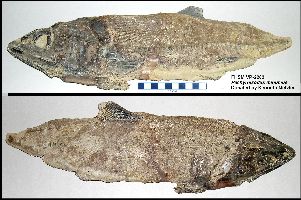

Order Elopiformes

Family Pachyrhizodontidae

Pachyrhizodontids

Larger

members of this genus have a heavy skull, with large, conical, curved teeth. The remains

of the jaws often have been mistaken for marine reptiles such as mosasaurs.

Pachyrhizodus

minimus

A small

predatory fish sometimes found complete with well preserved with scales and internal

structure.

|

LEFT: FHSM VP-326 - A very complete specimen in

the Sternberg Museum of Natural History; collected by G. F. Sternberg in Trego County in

1949 and described by H.W. Miller (1957): Intestinal casts in Pachyrhizodus,

an Elopid fish, from the Niobrara Formation of Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science,

Transactions 60(4): 399-401. |

|

RIGHT: FHSM VP-2282, a small Pachyrhizodus

minimus found by Ken Metzler in Ellis County (1968). |

Pachyrhizodus

caninus

A

medium sized predator, with long heavy jaws. The premaxillary of this species is

relatively easy to identify because it has one or two large fangs set inside the outer row

of teeth. Click here for photos of the skull and jaws of a very large Pachyrhizodus

caninus specimen (FHSM VP-2189) in the collection of the Sternberg Museum.

Pachyrhizodus leptopsis

A rare

species in the lower chalk, differentiated from P. caninus by the shape of the

teeth. While P. caninus teeth are round or oval in cross section, P.

leptopsis teeth are distinctly fluted.

Order Elopiformes

Suborder Elopoidei

Family Apsopelicidae

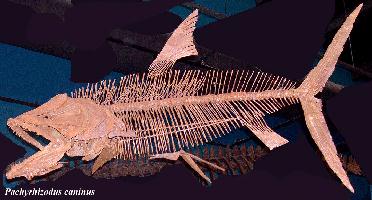

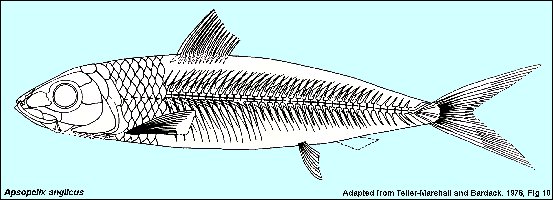

Apsopelix anglicus (Dixon 1850)

|

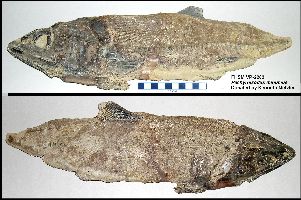

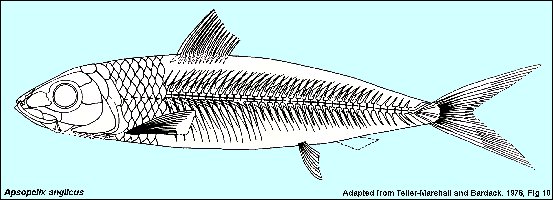

LEFT: Apsopelix

anglicus

(less than 1.5 ft) was a small, relatively uncommon fish from the Late

Cretaceous, with a wide distribution. It was first described by F. Dixon

in 1850. (adapted from Teller-Marshall and Bardack 1978, Fig. 10)

RIGHT:

The exhibit specimen at the Sternberg Museum. Apsopelix has been

collected mostly from the lower Smoky Hill Chalk in Kansas. Specimens are

usually preserved more or less complete, and often in 3-dimensions. Another

Sternberg specimen is here

|

|

|

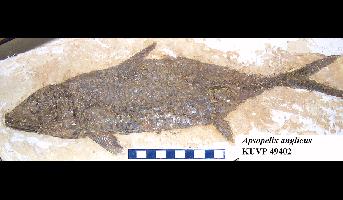

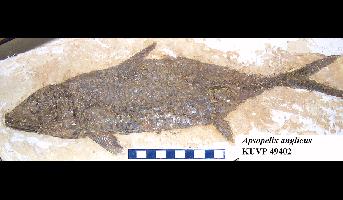

LEFT:

Apsopelix anglicus (FHSM VP-2056) - a mounted specimen in the

collection of the Sternberg Museum.

RIGHT:

An Apsopelix anglicus specimen (KUVP-49402) in the University of Kansas

collection. Collected by J. D. Stewart from Gove

County in 1997.

For

more information, see: Teller-Marshall, S. and D. Bardak. 1978. The

morphology and relationships of the Cretaceous teleost Apsopelix.

Fieldiana Geology 41(1):1-35.

|

|

Superorder Neoteleostei

Order Alepisauriformes

Cimolichthys nepaholica

Cimolichthys

was a common, small to medium size predatory fish. This species has a triple row of teeth

on the lower jaws and premaxillae, and no teeth on the maxillae. It also has very ornate

vertebra, similar to those of Enchodus, a related genus. In addition, in some

specimens, large scales or scutes are preserved along the lower portion of the body. This fish may have looked much like a modern barracuda

or freshwater pike. Based on two finds of Cimolichthys with the undigested

remains of their final meal still inside, it is known for certain that this fish fed on Enchodus

petrosus.

Enchodontids:

Fish in

the genus Enchodus were small to medium sized predators. Several species are well

represented throughout the chalk and are commonly found as fossils. The characteristic

that is most noticeable is the presence of large "fangs" at the front of the

upper and lower jaws.

|

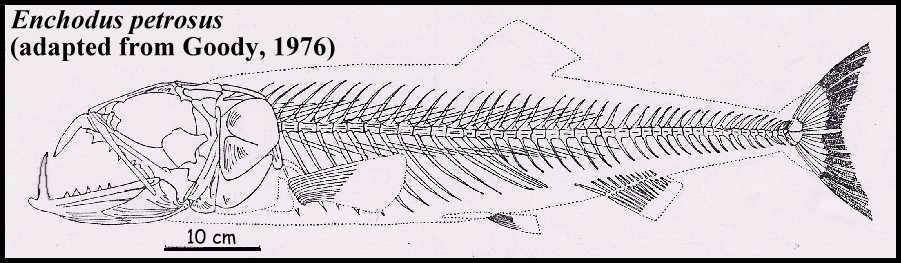

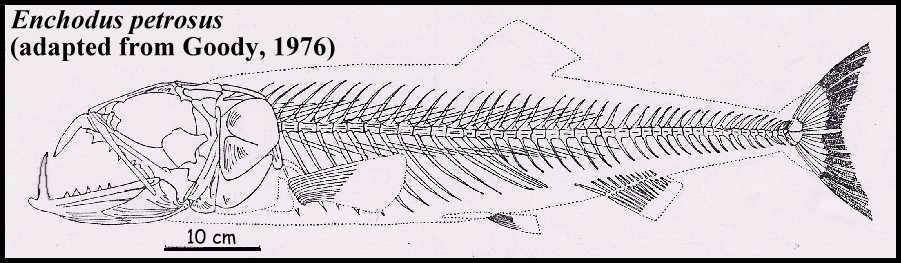

Above: A drawing of Enchodus petrosus showing the oversized

fangs which were typical of these fish. The upper fangs are slightly larger than the lower

ones. Note that when the jaws are closed, the large palatine fangs of the upper jaw are

between the large teeth on the lower jaws. This fish has also been called the

"Saber-toothed Herring" because of the appearance of these unusually large,

curved teeth. It is important to note, however, that Enchodus is not

related to Herrings and in fact, is a member of the same Order as modern Salmon. It is

possible that the fish may used it's unique teeth to feed on soft bodied animals like

squid (Tusotuethids). This genus of fish survived the end of the Age of Dinosaurs by

several million years and is well represented in the fossil record around the world. |

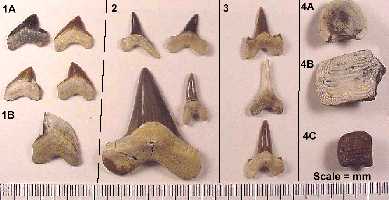

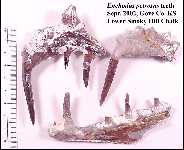

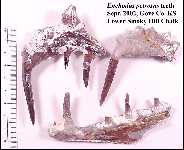

Typical

examples of Enchodus remains that are found in the Smoky Hill Chalk. Top row: Two

palatine bones with partial fangs; Bottom row: two lower jaws. |

|

Enchodus petrosus:

This

fish was the largest of the Enchodontids found in the Smoky Hill Chalk (Niobrara Fm) of

western Kansas.

|

LEFT:

This is a picture of a fairly complete and unusually large set of Enchodus petrosus

teeth found by the author in September, 2002. The fish would have been 4-5 feet

long. It is little wonder that they have been referred to (incorrectly) as the

"Saber-toothed Herrings" of the Cretaceous. They are more closely related to

modern salmon. |

Enchodus

gladiolus

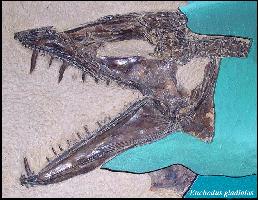

Another

small predatory fish, with elongated fangs on the lower jaws and the palatine bones of the

skull. E. gladiolus was a small sized predator, with palatine teeth that reached

two inches in length. Pectoral fins are long

and delicate, and may have given the fish the capability to 'fly' in a manner similar

to modern flying fish.

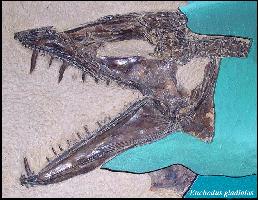

|

LEFT:

This specimen was found in the lower Smoky Hill Chalk by Pam Everhart and donated to the

New Jersey State Museum.

RIGHT:

The exhibit specimen of Enchodus gladiolus at the Sternberg Museum of Natural

History. It appears to be missing the palatine tooth at the front of the upper jaw. These

teeth were shed and replaced periodically as the fish grew larger and the length of the

jaws increased. |

|

Enchodus dirus - A small, relatively unknown species

of Enchodus.

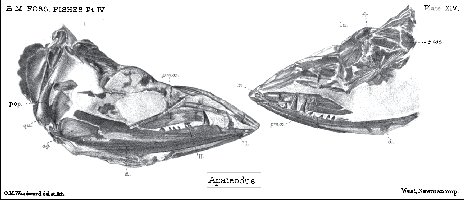

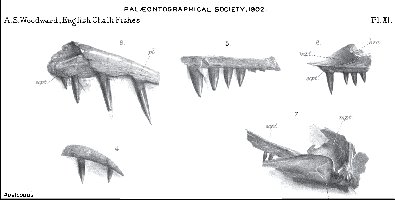

Apateodus - The genus Apateodus

(Teleostei: Aulopiformes) was

first described from specimens in the English Chalk by Woodward

in 1901. It is a medium sized bony fish that apparently had a worldwide

distribution in the Late Cretaceous, but is only known from a few specimens with

post-cranial material (also in Russia and India).

A reasonable complete specimen (AMNH FF11560; Below) was collected by George Sternberg from Wildhorse

Canyon in SW Trego County in 1949 and sold to the American Museum of Natural

History.

|

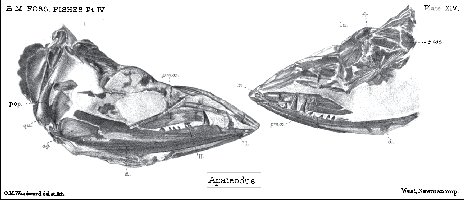

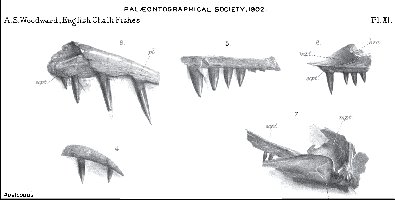

LEFT: From Plate XIV in Woodward, 1901, showing two

skulls of Apateodus.

RIGHT: From Plate XI in Woodward 1902, showing the teeth of Apateodus. |

|

|

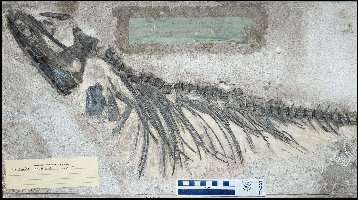

LEFT: Apateodus sp. (AMNH FF11560) - Description

reads: "Unidentified

fish skull and partial skeleton on plaster base 27 1/2" long by 14

1/2" wide. Locality Gove County, Kansas, about 2 1/2 miles due east

of Castle Rock. In Niobrara Cretaceous chalk. Found about 1949

by George F. Sternberg."

Photo by Matt Friedman; used with permission of Matt Friedman and the

American Museum of Natural History.

RIGHT: Closer view of the skull of AMNH FF11560. Photo by Matt

Friedman; used with permission of Matt Friedman and the American Museum of

Natural History.

|

|

|

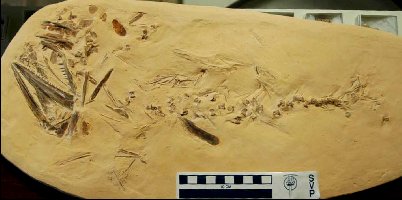

LEFT: A smaller specimen of Apateodus sp.

(KGM0031) collected by Chuck and Barbara Bonner from the upper chalk,

eastern Logan County, and displayed in the Keystone

Gallery, south of Oakley, Kansas. Detail

of the vertebral column HERE. The vertebrae appear to be very similar

to those of Enchodus or Cimolichthys. Photos by Matt

Friedman; used with permission.

RIGHT: Detail of the jaws of the Bonner specimen. The way that

the teeth are slanted forward in the jaws is unusual. Photo by

Matt Friedman.

|

|

|

LEFT: This specimen of Apateodus (CMC VP 6941) was

collected by a friend of mine (Pete Bussen) from the upper chalk in

western Logan County and donated to the Cincinnati Museum Center. The

photo shows both lower jaws. The large bone at the upper left is the

ceratohyal. The specimen was subsequently described as a new species (A.

busseni) by Fielitz and Shimada (2009). Photographed in 2003.

RIGHT: Detail of the dentary showing the characteristic blade-like

teeth that are inclined anteriorly. Close-up

HERE.

Fielitz, C. and Shimada, K. 2009. A new species of Apateodus (Teleostei:

Aulopiformes) from the Upper Cretaceous Niobrara Chalk of western Kansas, U.S.A. Journal

of Vertebrate Paleontology 28(3):650-658.

|

|

|

LEFT: Another portion of the specimen showing the

anterior portion of the vertebral column and the back of the skull of the

type specimen of Apateodus busseni (CMC VP 6941). Close

up HERE.

RIGHT: The base of the caudal fin of the type specimen of Apateodus

busseni (CMC VP 6941).

|

|

Family

Dercetidae

Dercidids

(Stratodus apicalis) - A relatively rare fish with a narrow, eel like body

and numerous small teeth. The picture at below left shows the long, slender vertebral

column of what had been a fairly complete specimen (EPC 1990-14) as found in the lower

Smoky Hill Chalk.

|

LEFT: The disarticulated skull and jaws of a

large Stratodus apicalis (KUVP 23) collected from Logan County by S. W.

Williston. RIGHT: Stratodus apicalis

specimen as found in the Late Coniacian Smoky Hill Chalk (Gove County). Head is to the

lower left in the photo. Hammer is 13 in / 33 cm. |

|

|

LEFT:

Vertebrae and jaw fragments from the specimen at above right.

RIGHT:

A close-up of the jaw showing the fine, comb-like teeth. (Scale = mm) |

|

Superorder Acanthopterygii

Order Beryciformes

Family Holocentridae Richardson (1846)

Genus Kansius Hussakof 1929

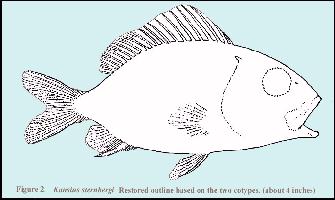

Kansius sternbergi

| Near the middle of the chalk, large Inoceramid

shells have been found with schools of small Holocentrid fish preserved inside. Sometimes

numbering in the hundreds, these fish were apparently trapped inside the shell when the

clam died and the shell closed. Although several new species have been found inside clam

shells, most have not yet been described. The remains of one species, Kansius

sternbergi (below), have been found inside and outside of clam shells. This unusual association was first noted by G.F. Sternberg in 1930 on

the basis of a group of "twenty or more" small fish discovered inside an

inoceramid clam shell in northern Trego County by M.V. Walker. The fish averaged 3.5

inches long (his SP-225-30). Sternberg also mentioned a similar discovery from the Smoky

Hill Chalk west of Webster, Kansas. These associations are most common in the early

Santonian, near Marker Unit 8. See also: Stewart.

J.D. 1984. Taxonomy, paleoecology, and stratigraphy of

halecostome-inoceramid associations of the North American Upper Cretaceous

epicontinental seaways. Unpubl. doctoral dissertation, University of

Kansas, 201 pp.

|

|

|

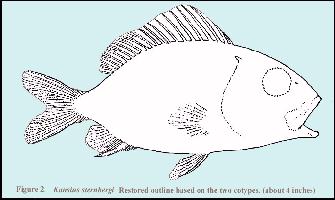

LEFT:

Kansius sternbergi - A small fish (about 3-4 inches) found rarely

in the Chalk. Drawing from Hussakof (1929). Pictures of the type specimen (FHSM VP-19) in

the collection of the Sternberg Museum are HERE and HERE.

RIGHT:

A more complete specimen of Kansius sternbergi (FFHM 1972-128) on an inoceramid

clam shell in the collection of the Fick Fossil and

History Museum, Oakley, KS. |

|

Superorder Paracanthopterygii

Order Polymixiiformes

Family Polymixiidae

Genus Omosoma Costa (1857)

Omosoma

garretti - Omosoma was described first from Europe and

the Middle East, but is found in greater numbers in the Smoky Hill Chalk (ibid., p. 357).

Other specimens have been collected in Gove County, but preservation of the skeleton,

especially the skull, is usually poor due to the small size. This small (4-7 cm) fish was

first described from Kansas by Bardack (1976) from specimens found in the inside of an

inoceramid shell from the Garrett Ranch in Trego County

|

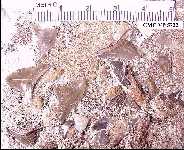

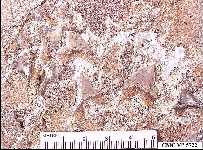

LEFT: An unusual slab of chalk collected from Gove County in 1975

containing part of a school of Omosoma garretti FHSM VP-5115) on exhibit at the

Sternberg Museum.

RIGHT: A

detail from the Platyceramus platinus shell that the VP- 5115 specimen of Omosoma

garretti was laying on. |

|

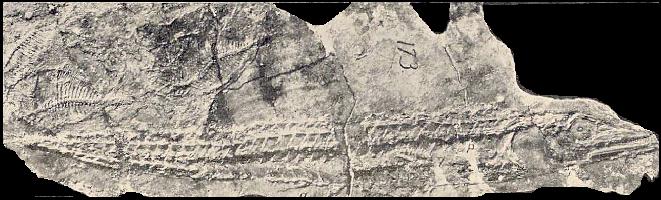

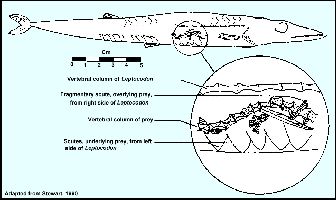

Leptecodon rectus

|

LEFT: A more recent (2004)

picture of the type specimen of Leptecodon rectus - KUVP 35, in the collection of

the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History. The specimen is laying on a piece of

inoceramid shell. |

|

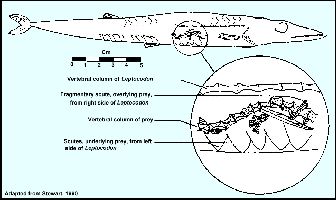

LEFT: It turns out that Leptecodon

was an accomplished predator... both of the known specimens included stomach contents...

the remains of a smaller Omosoma garretti was found inside the above specimen.

Figure adapted from Figure 5 in: Stewart, J. D., 1990. Niobrara Formation symbiotic fish

in inoceramid bivalves. p. 31-41 In S. Christopher Bennett (ed.), 1990 Society of

Vertebrate Paleontology Niobrara Chalk excursion guidebook. Museum of Natural History and

the Kansas Geological Survey, Lawrence, KS.

See also:Stewart.

J.D. 1984. Taxonomy, paleoecology, and stratigraphy of

halecostome-inoceramid associations of the North American Upper Cretaceous

epicontinental seaways. Unpubl. doctoral dissertation, University of

Kansas, 201 pp.

|

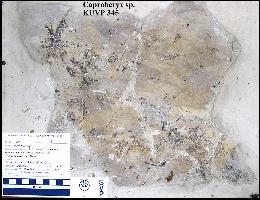

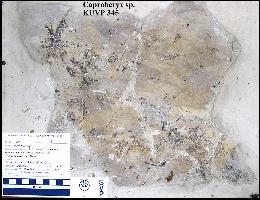

Caproberyx

sp.

|

LEFT: A section of inoceramid shell (Platyceramus

platinus) with the disarticulated remains of two or three small fish (Caproberyx

sp.: KUVP 345) inside. Collected by H. T. Martin from the Smoky Hill Chalk (Gove County)

in 1915. |

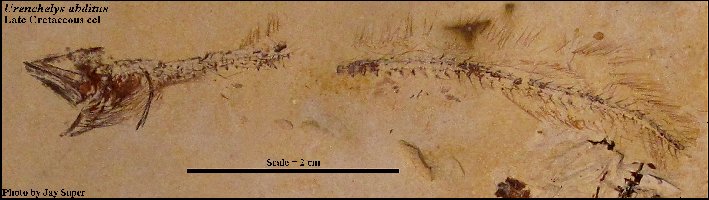

Order

Anguilliformes

Family Urenchelyidae

Genus Urenchelys

Woodward

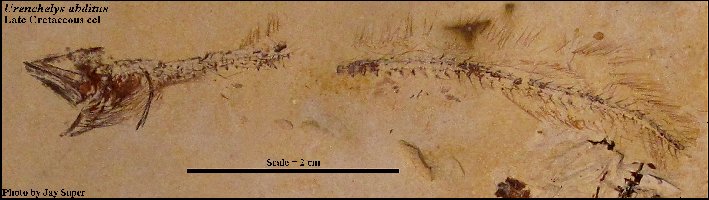

Urenchelys abditus, Wiley

and Stewart, 1981

|

LEFT: This is only the second specimen of a Urenchelys

abditus (a tiny, 3-inch long eel) ever collected from the Smoky Hill

Chalk of western Kansas. It was discovered inside a inoceramid clam shell

in southeastern Gove County in 2010 by Kris Super. It was first described

as a new species by Wiley and Stewart in 1981 (CLICK

TO ENLARGE):

Wiley, E.O. and J.D. Stewart. 1981. Urenchelys abditus,

new species, the first undoubted eel (Teleostei: Anguilliformes)

from the Cretaceous of North America. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology

1(1):43-47. |

Subclass Saurcopterygii

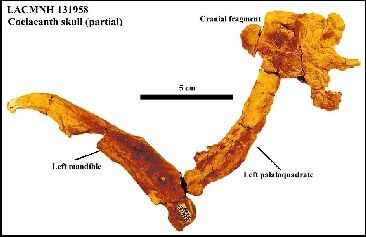

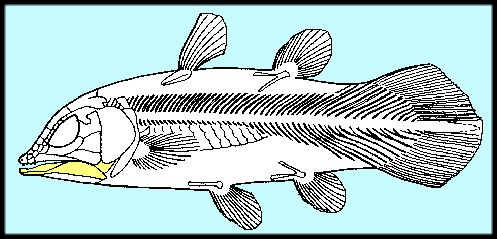

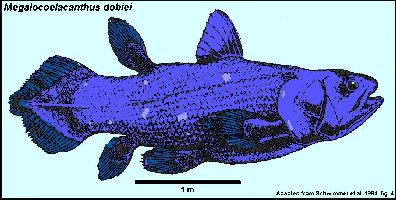

Coelacanths:

Until

recently, there were no coelacanths known from the chalk. Coelacanths are well represented

in the English Chalk (below RIGHT). The discovery of a partial skull by Pam Everhart in 1990

was the subject of a presentation (Stewart, J.D., et al. 1991) at the annual meeting of

the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, and also at the Kansas Academy of Science annual meeting in

1995 (Everhart, et al., 1995).

Since the original discovery, another set of fragmentary remains has been

collected (J. D. Stewart, pers. comm. 1994). In addition, recent discoveries of

the remains of a giant coelacanth in the Smoky Hill Chalk of Lane County, Kansas

have been assigned to a genus and species (Megalocoelacanthus

dobiei) first reported from Alabama by

Schwimmer et al. in 1994 (see also Schwimmer 2006). The latest report by Dutel

et al (2011) describes a fairly complete and well preserved skull in the

collection of the American Museum of Natural History.

Although coelacanths are a very old family of fish,

they are not extinct as once thought and are still present in the Indian Ocean near

Madagascar, and in the East Indies.

Coelacanth

References:

Dutel,

H., Maisey, J., Schwimmer, D., Janvier, P. and Clément, G. 2011. Giant

coelacanth Megalocoelacanthus dobiei from the Upper Cretaceous of

North America

and its bearings on the phylogeny of Mesozoic coelacanths. Journal of

Vertebrate Paleontology 31(Suppment to 3):103.

Everhart,

M. J., Everhart, P.A. and Stewart, J.D. 1995. Notes on the biostratigraphy of

a small coelacanth from the Smoky Hill Chalk Member of the Niobrara Chalk (upper

Cretaceous) of western Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions

14(Abstracts):20.

Schwimmer,

D. 2006. Megalocoelacanthus dobiei: Morphological, range and ecological

descriptions of the youngest fossil marine coelacanth. Journal of Vertebrate

Paleontology 26(Supplement to 3):122A.

Schwimmer,

D.R. 2009. Giant coelacanths as the missing planktivores in southeastern Late

Cretaceous coastal seas.

Geological

Society of America, 58th Annual Meeting, Paper No. 3-1 (abstract).

Schwimmer, D. R., Stewart, J.D. and Williams, G.D.

1994. Giant fossil coelacanths of the Late Cretaceous in the eastern United

States. Geology. 22:503-506.

Stewart, J.D., Everhart, P.A. and Everhart,

M.J. 1991. Small coelacanths from Upper Cretaceous rocks of Kansas. Journal.

Vertebrate Paleontology 11(Abstract, suppl. to 3):56A.

Rare

fish - There are several genera and species of fossil fish that are sometimes

represented only by few remains or even just a single specimen from the chalk. These

include: Trachichthyoides, Luxilites striolatus (KUVP 295),

Paraliodesmus, and Belonostomus.

References

on Sharks and Fish in the Western Interior Sea

Continued

on next page................................. A Field Guide to Fossils of the Smoky Hill Chalk: Part 3 - Marine

Reptiles

Credits

- Earl Manning and many others have provided me with information regarding the classification of fishes from the

Smoky Hill Chalk.

BACK TO INDEX