|

The 1999 Cincinnati Museum Plesiosaur

Dig

Copyright © 2000-2009 by Mike Everhart

Updated 02/13/2009

Looking west across the prairie near

McAllaster Butte in Logan County, Kansas. The dig site is in a large gully, just

right of center, below the truck. |

We will probably never know why or how the plesiosaur

died 80 million years ago. After death, its body may have sunk to the bottom

of the Western Interior Seaway for a short time. Then, as it decomposed, gases were

trapped inside the abdomen. Bloated by these gases, the plesiosaur was lifted back

to the surface where it probably floated for several days. Weighing several thousand

pounds, the large carcass would have attracted sharks who scavenged at the paddles and

other exposed flesh, but did little major damage. In the warm water, however, the

relentless efforts of bacteria and other micro-organisms swiftly destroyed the muscles and

ligaments that held the plesiosaur together. At some point, the abdominal wall

ruptured, releasing the trapped gases and the heavy body sank quickly to the mud bottom.

spilling ribs and gastroliths along the way. The impact was violent enough to tear

apart the skeleton even further, and to scatter some of the rib cage and other bones

across the sea floor. Small scavengers fed on the remaining flesh for some

time. The bones were slowly covered by fine sediments and were eventually buried

under hundreds of feet of shale. Millions of years later, the sea became shallower

and then disappeared all together as the land was lifted upward. The hundreds of

feet of rock that had buried the bones was slowly eroded away and the bones were finally

exposed to the light of day. ..... Of course, this is fiction..... we really don't know

what happened.

The dig on this plesiosaur actually started

four years ago in the spring of 1995 with the discovery of an articulated series of

plesiosaur caudal vertebrae eroding from the side of a steep slope in the Sharon Springs

Member of the Pierre Shale in Logan County, Kansas. This plesiosaur was

found by a young girl (Katie Swann) on a school field trip led by our friend, Pete Bussen. Other remains that have been found at

this site include a Platecarpus mosasaur, the

only Globidens remains (a shell crushing mosasaur)

ever found in Kansas, a concretion full of Baculites

maclearni [mclearni*], and other fragmentary remains

of marine reptiles and fish. More info on the Globidens can be found here; pictures of the Platecarpus skull can be found on

the Platecarpus Collection page of the Virtual Mosasaur Museum.

* Postscript: the proper spelling of the species

name, contrary to Cobban (1993), is mclearni; from B. mclearni Landes

1940

|

This is a 1995 picture of the caudal (tail) vertebrae of the

plesiosaur which had eroded out from the edge of a concretion in the Pierre Shale on the

steep side of a gully. Camera is facing to the east. |

|

A close up of several of the caudal vertebrae laying end to end

and still articulated. Scale is one foot. |

The discovery was made even more interesting by the fact that the first

plesiosaur to be discovered in the United States (Elasmosaurus platyurus) was

found by Dr. Theophilus H. Turner, just a mile to the south,

near McAllaster Butte, more than a hundred and thirty years earlier (1867). Turner was an

Army doctor stationed several miles to the southwest at Fort Wallace, at a time

when the U.S. Army was protecting the workers who were building the first transcontinental

railroad. The "rest of the story" on that particular specimen involved shipping

it by rail to E. D. Cope, the

famous paleontologist, in Philadelphia where it was quickly prepared and put on exhibit

.....with the plesiosaur's

head on the wrong end. Cope published several articles

describing this strange animal and Cope’s mentor, John

Leidy, was the first to point out the error. O. C. Marsh, Cope's

rival, later claimed that he had mentioned the error to Cope, and

said it was the reason that Cope hated him. This incident has been erroneously

blamed for what became the 'Great

Feud' between these two famous American paleontologists. However, the head was

quickly moved to its rightful place and the incident was largely forgotten until Marsh

raised the issue twenty years later (1890). The specimen has been in the collection of the

Philadelphia Academy of Natural

Sciences ever since.

|

The skeleton of Styxosaurus snowii, a long-necked

plesiosaur (Adapted from Buchanan, 1984) |

Pete identified the material as the remains of a plesiosaur and told the

landowners what had been found. Then he called David Parris with the New Jersey State

Museum to see if he was interested in digging the specimen. Dave, of course, was

very interested because plesiosaur skeletons are not all that common (a friend of ours at

the Denver Museum once said, half-seriously,

that they were so rare that a paleontologist is only entitled to find one in a

lifetime). By then, Pete had three or four to his credit.

In April, Dave came back to Kansas to look at the site and was met with a

freak snowstorm that dumped 6 or more inches of snow

on the area in the space of a couple of hours. He managed to see enough, however,

that he decided to arrange a dig, and the wheels were set in motion to work on the site in

August of that year.

As is normal for Kansas in August, it was very hot and very dry when Dave

Parris brought his field crew down from South Dakota. The remains were eroding from a

steep, south-facing slope and the nearest tree was half a mile away. Aside from the small

‘bench’ where the vertebrae and an associated concretion were exposed, there was

no place to stand on the shaley slope. The first order of the day was to carefully remove

the shale overburden from the top and either side of the concretion, and begin to

determine the extent of the find. Almost immediately, jumble of short ribs

(gastralia) and a few small stones (gastroliths) were found on the east side of the

concretion. This provided an indication that there was more of the fossil inside the hill,

and a preliminary idea that it was going to be somewhat disarticulated. (The bones of

the first plesiosaur that the New Jersey crew dug in 1991 were generally still

articulated). The other concerns at this point were which way the animal was laying, how

much might be there, and how much overburden was going to have to be removed to get to the

remains. Since the shale sloped steeply upward about 12 feet above the fossil, any digging

was going to require the removal of a lot of the overlying shale first.

|

Once the overburden was cleared off the exposed concretion, work

began on locating bones that were still in the shale. |

|

The first remains we found were lots of ribs from the belly of the

plesiosaur. In addition to the normal dorsal ribs that come off of the vertebrae,

plesiosaurs had three additional ribs (gastralia) that covered their belly. There

were also three gastroliths and a fish vertebra found in this area. |

|

These dorsal processes were all that remained of the caudal

vertebrae at the end of the tail. Those vertebrae had eroded out first, years

earlier and were either destroyed by weathering or buried under the loose shale at the

bottom of the slope. We looked but were unable to find them |

|

Katie (left) discovered this plesiosaur fossil on a school field

trip in 1995, and came out for both the 1995 and 1999 digs. She is standing behind

concretion #1, next to the spot where the caudal vertebrae were eroding out. The partial

pelvis of the plesiosaur is visible in the foreground. North is to the right. |

|

A picture of what is probably the right half of the pelvis of the

plesiosaur. The smaller bone to the lower right is the ileum. Scale is one meter.

Picture was taken while standing on top of concretion #1. North is to the

left. |

|

Ventral view of the pelvis of Elasmosaurus platyurus

Cope. (Adapted from Welles, 1962) |

|

Another view of the partial pelvis. Scale is one

meter. The other half was eventually found (1999) inside a nearby concretion. |

Time was short for the New Jersey crew since they had already been in the field

for several weeks. A exploratory cut was made about 10 feet wide and 6 feet deep into the

slope. More concretions and ribs were found. In mid-afternoon, a large piece of bone was

found and general work slowed as it was uncovered. The bone turned out to be half of the

plesiosaur’s pelvis, laid flat and in excellent condition. Based on the shape, David

tentatively identified the plesiosaur as an Alzadasaurus (now called Styxosaurus,

see Carpenter, 1999, citation below). This useful bit of information assured us that we

were working on a long-necked plesiosaur and not a short necked pliosaur (which are also

found in this formation). We had also cleared enough area by that time to give us a good

idea that the remains were going into the hill and we had a good chance of recovering more

of the animal. (The other possibility which we were afraid of was that the front end of

the animal had eroded out years ago and we were simply finding the last few pieces of the

skeleton).

The next day, caudal vertebrae and the half pelvis were jacketed and removed

along with several exposed bones. These included the dorsal spines of several caudal

vertebrae from the end of the tail that had apparently eroded away and were already lost.

Then the remaining material was covered and secured until the crew could return. As it

turned out, David was only able to return to the site one more time, in August of 1996.

Shortly after that, the New Jersey State Museum was host to the highly successful

"Russian Dinosaurs" exhibit and there just was not enough time for David to

break loose and come back to Kansas to finish the dig. Having waited 80 million

years to see the light of day, the bones of the plesiosaur would have to wait a few more.

In 1998, while Glenn Storrs

and the Cincinnati Museum crew were working on another Pierre

Shale plesiosaur, the suggestion was made that he might contact David Parris and see

if arrangements could be made for the Cincinnati Museum to finish the dig on the New

Jersey specimen. David was most gracious in agreeing to Glenn’s proposal and plans

were made to re-start the dig in June, 1999. Which brings us to this year’s

Cincinnati Museum plesiosaur dig.........

Glenn Storrs and 5 volunteers from the Cincinnati area arrived in Wallace,

Kansas on June 20, 1999 with an eye on the sky. The weather had been cool and unseasonably

wet for June in Kansas. In fact, the wheat harvest was just barely started across the

State because fields were too wet for the combines. The group camped out at the roadside park in Wallace and got set to

spend as much time as was needed to recover the plesiosaur. The crew reached the dig

site on Monday morning and discovered that the protective burlap and dirt covering that

had been placed over the remains had ‘gone away’ sometime during the past three

years. Nothing was harmed, however, and work started on cleaning up the exposed area so

that plans could be made for the next stage of the dig. Using picks and shovels, the crew attacked the slope and began to enlarge the working

area, moving the loose shale further down the hill. Things were pretty slow going at

the start as everyone adjusted to working conditions. There was a lingering concern

that nothing else would be found, but additional bones were soon discovered going back

into the hill. Glenn was pretty optimistic that a major

portion of the plesiosaur was still there. The day ended with everyone tired, dirty, ready

for supper and some rest. (Photos in the above paragraph by team member, Tom

Bantel)

|

Day 2 (Tuesday) Tuesday began as a repeat of the first day, with

the crew using picks and shovels to tear off the side of the hill in order to get a larger

working area exposed. (Photo by team member, Tom Bantel) |

|

Late in the morning, Phil Collins, the property owner showed up to

view the progress and decided that he could help by bringing in a heavy duty front end

loader. By that time, everyone was more than willing to have some mechanical help with the

removal of the overburden. A couple of hours later, Phil returned with a very large

front loader and proceeded to dig a ramp down to the level in the shale where the fossil

was exposed. (Photo by team member, Tom Bantel) |

|

Even with heavy equipment on the job, it was still slow going. The

unweathered shale was tough and contained numerous hard concretions. Horsepower won the

battle, however, as tons of shale were pushed over the side of the hill. (Photo by

team member, Tom Bantel) |

Later, when Pete Bussen arrived at their camp, the group kidded him that they

had moved 30,000 cubic feet of dirt off the fossil that day. Pete, not knowing that they

had received a lot of help, decided that they had been out in the sun far too long. That

night, another volunteer, Richard Swigart, arrived all the way from Illinois to help with

the dig.

Day 3 (Wednesday) The landowner returned to finish the job with the high loader

and the dig crew began to work on the remaining 12 to 18 inches of shale overburden

above the fossil. Soon there were two parallel lines of concretions exposed, heading

generally to the north-northeast. The concretions on the east side seemed to be filled

with bones while those on the west did not. Glenn was happily locating and identifying

various parts of the plesiosaur; limb bones, vertebrae, ribs, etc. From all appearances,

the plesiosaur had been fairly complete when it hit the bottom.

Most of the bones were located in the general areas where they were expected to

be, but very few were articulated. The suspicion grew that this animal had bloated and

floated for quiet some time, and was beginning to fall apart before it came to rest on the

muddy bottom of the Western Interior Seaway. At the close of the day, the crew covered the

site with a tarp to protect the exposed bones.

|

"The Belly of the Beast" - This cropped picture of a

large elasmosaur mounted overhead in the Denver

Museum of Natural History provides a quick lesson in plesiosaur anatomy and shows the

approximate extent of the skeletal material recovered during the June, 1999 dig. The

interlocking gastralia provide a nearly solid shield of bone to protect the belly of the

plesiosaur. |

Angie, another volunteer from Kansas, Pam and I arrived in Oakley, Kansas

(about 30 miles from the dig) Wednesday evening. We were staying in a motel

during our time on the dig and not roughing it like most of the rest of the crew.

Years earlier, we had decided that it’s much easier to put up with the sun, the dirt

and the aching muscles when you have a shower, air conditioning, and a comfortable bed

waiting for you. That night, however, I was awakened several times by the sound made by

strong wind gusts as a major storm front moved through. I was concerned about the people

staying in tents, and what the rain was doing to the fossil, and to the dirt roads that we

had to travel to get to the fossil the next morning.

Day 4 (Thursday) When we got ready to leave that morning, the sky was still

cloudy and a light rain was falling. Figuring that there was not much need to hurry, we

got on the road to the dig shortly after 9:00 AM. About thirty minutes later, we pulled

off the highway at McAllaster Buttes, and took a brief

look at the dirt road leading to the site. It looked like a truck had ‘mudded’

it’s way out to the highway a few minutes earlier, but no one had driven in since the

rain. Then we drove into Wallace and the roadside park where everyone was camped.

They were still cleaning up from breakfast when we arrived. After greetings and

introductions were out of the way, we got to hear the various horror stories about how

strong the wind was and how much water got into the tents. Pete Bussen was there, too, and

said that the surrounding areas had gotten up to an inch and a half of rain. He was

optimistic that the road and the shale would dry out quickly, and not prevent us from

working at the site.

After spending an hour or so in the camp, and the nearby Wallace Museum (a nice

place to visit), we decided take a chance and see if we could get into the dig. We

convoyed out to the turn-off and headed down the dirt road. The first quarter mile or

so was still pretty slippery (as Pete had predicted) since it was built on a shale

base, but once we started down the hill on the other side, the road dried out quickly.

Several of the people in cars parked along side the road and walked in about 200 yards to

the dig site while Glenn and I drove our vehicles across the prairie and parked on the

flat ground above the excavation.

The first thing we noted was that there had been a pretty good rain on the

site. Fortunately, they had put a tarp down to protect the fossil the previous

evening. Even so, quite a lot of water (and mud) had accumulated around the remains.

We pulled off the tarp, then began draining puddles and cleaning up the mud flows. Nothing

was harmed, but the crew endured less than the best working conditions until later in the

afternoon when things began to dry out. Glenn gave the new crew members a quick summary of

where bones were exposed, and I provided the background for the location of the caudal

vertebrae and pelvic material that had already been removed. Then the real work started

and we began clearing shale from areas that were above the bone layer. A few more bones

were found but mostly the remains were clustered together along the axis of the eastern

group of concretions.

|

The day passed fairly quickly and we said ‘good-bye’ to

a couple who had to return to Cincinnati. Later in the afternoon, a photo-journalist (Fred

Solis) arrived to interview the dig crew and to take pictures for a news story he was

writing. The site was tarped again and we left the field about 6:30 PM. Angie also

had to leave to go back to her real job the following day, so we said ‘good-bye’

to her, too. (Photo by Angie) |

|

|

Here are four of Fred's

professional photographs of the dig (and me, for a change). They are slightly larger

(100kb) than other photos on this page and will take longer to load. Copyright ©

1999 by Fred Solis. |

|

|

|

Things were more than just a little muddy after we pulled the

tarp off Thursday morning. Here Glenn Storrs gets down to the dirty job of cleaning

mud off the the exposed bones. |

|

This picture of dorsal ribs and gastralia shows what got wet and

what didn't. |

|

Who said field work isn't glamorous? Glenn certainly seems to be

enjoying the mud. Hmmmmmm......... looks just like a famous scene from

"Jurassic Park". |

|

This picture was taken while I was standing on the last

concretion in the main (east) series, looking southward toward original concretion #1 that

contained the caudal vertebrae. |

|

Four years older now than when she discovered the plesiosaur,

Katie and her dad watch as the crew cleans up the working area after the rain. |

|

Mud and wet shale are puddled around two of the cervical vertebrae

found near the middle of the east line of concretions. |

|

A good view of the dig site from the bottom of the gully to the

south. We had set a up an awning on top of the hill to provide a little shade.

It was a nice idea, but the wind came up about noon and threatened to blow the little tent across the State line into Colorado. |

Day 5 (Friday) Fred Solis wanted to take some early morning pictures of the

site, so I drove him and his daughter, Erin, to the site about 7:30 AM. We were concerned

that there were too many clouds for good pictures when we left the motel, but as we went

further west, the sun broke through and we figured that he get the conditions he wanted

for the shoot. When we walked into the site, however, we found that we had not planned on

part of the hill being between us and the sun. We uncovered the site and Fred took some

other shots while we waited for the sun to creep over the hill. With our mission

completed, we went back into town for breakfast. Expecting to meet the rest of the crew

coming into the site, we did not leave a note to explain why the remains had been

uncovered. It did create an interesting mystery for them until we returned to admit our

guilt.

We got back to the site later that morning and found a place on the ground to

continue with our share of the digging. Bored with this activity, Pam went off around the

next hill on her own search for fossils. A little later, someone noticed that she was

waving to get my attention from about a hundred yards away. This usually means she’s

found something new and wants me to come see it. I was ready for a break and to stretch my

cramped legs for a while, so I grabbed my tools and slid down the hill. When I got closer

to Pam, I found out that she had slipped on some loose shale, fallen and twisted her

ankle. Barely able to hobble on one leg, she managed to get back to a spot where she could

be seen from the dig. I went back to our van and drove it around to where she could get

in. While she could deal with the pain, she was obviously not going to be doing much

moving around. We got her comfortable in the van and I went back to the dig.

The landowners (Phil and his wife, Debbie) arrived at the site a little later

to check on progress. Things had dried up enough that Phil thought he could take off

another layer of the shale, so he fired up the front loader and we all took a break to

watch. He was able to cut off some of the material, but there were some soft spots that

were still too wet for him to drive over. After he finished, we broke out the portable

jack hammer and took turns cutting through the shale on the north side of the fossil, one

layer at a time.

We were really hoping to find signs of the neck and head of the animal in this

area, but it turned out to be virtually empty of bones. The rest of the day was spent

cleaning and localizing the remains that we had found. It was pretty hot and humid that

afternoon, and everyone was more than ready to leave the site by 6:00 PM.

|

The shale eventually dried out and we resumed cleaning up with

brushes. Here Richard Swigart watches as Glenn examines a bone near the center of

the specimen. |

|

Phil Collins came by again and helped the cause by removing

another couple of feet of shale off the north side of the dig. While most of the

detailed work had to be done with small tools and brushes, it was really nice to have some

heavy equipment around to get us down to the working level. Thank you, Phil!! |

|

"Nothing runs like a Deere, John Deere, that is." From left to right,

Katie, her mother, Debbie Collins, Pete Bussen and Jim Clark watch as Phil Collins moves

another bucket load of shale. |

|

Richard Swigart (with shovel), Katie's dad, and Glenn Storrs watch

the high loader from the other side as it removes part of the hill. |

|

A view of the dig with a little less shale on top. At this

point, the ground was still too wet to go further. |

|

Catching the photographer at work. Fred Solis is taking a

picture of Glenn Storrs doing some serious work with the portable jack hammer while Jim

Clark makes an effort to get out of the picture. See Fred's story here. |

|

The ribs were piled together without any apparent order.

With five pieces to each set of ribs, a plesiosaur dig can encounter a lot of rib bones! |

|

Caution! Man with power tool! The portable jack hammer

was a real labor saver on this dig, allowing us to quickly cut through 6 to 10 inches of

shale at a time. |

|

Richard Swigart and Jim Clarke prepare to clean up the site at the

end of the day. Glenn kept telling us that "A clean dig is a happy dig" as

we shoveled and swept away the debris of the day before covering the remains for the

night. |

|

Feel the heat!! This picture was taken late in the afternoon

on Friday, looking toward the northeast. The temperature was about 95 degrees (F),

there was no wind, and we were sweating buckets! |

Day 6 (Saturday) At the restaurant, we met another volunteer (Steve

Johnson) and another photo-journalist (Ron Williams), both of whom are from Kansas. There

were no clouds in the sky when we arrived on the site and it was pretty apparent that it

was going to be a typical Kansas summer day. The worst part about it was that there was no

wind blowing and the heat was pretty oppressive. Although the wind did pick up a bit later

in the afternoon, we were pretty well ‘steamed’ by the time we covered the dig

that evening. Ron Williams did his thing, filming the dig site and interviewing the crew

through the morning hours.

My first job on the site that morning was to explore along the edge of the

concretion that had been nearest to the half pelvis that we had found in 1995. These

paired bones are large and heavy, and it is not likely that they would be found widely

separated. I dug around and under the concretion without finding anything and began to

wonder what had happened to scatter the remains of this animal so completely. Later that

afternoon, Glenn walked by where I had been working and asked "What’s

this?" as he pointed to a large piece of exposed piece of bone. Sure enough, I had

found the other half of the pelvis that morning and had not been able to see it against

the similar color and texture of the concretion around it. Embarrassing as it was for me,

I was glad that the piece was where it was supposed to be. I can always claim it was the

change in the lighting that made it more visible.

We broke for lunch with the consensus that we had exposed most of the bones

that were there and that it was time to document the locations and start picking them up

for packing.

That afternoon, we rolled out sheets of plastic over the remains and used magic

markers to show where the bones and concretions were located. This created a permanent

record for the dig and, in addition to the pictures and drawings that had already been

done, helps to document the locations and spatial relationships between the various bones.

Once we had everything marked on the plastic, we began to take the bones up one at a time,

assigning a number to each was we moved through the site. The bones were wrapped in

aluminum foil and packed away for their journey back to Cincinnati. By the end of another

long day (7:00 PM), we had the site pretty much cleared of the smaller ribs and limb

elements, and Glenn had begun to apply plaster jackets to the concretions where bone was

exposed.

|

Find the bone......... This is a picture of the east side of the

#1 concretion. I had spent thirty minutes clearing the shale away from the

concretion in an attempt to find the other half of the pelvis. |

|

Steve Johnson digging shale in the area where we anticipated

finding the head and the rest of the neck. We came up empty in our search and hoped

that it was somehow included in the concretions that contained most of the rest of the

animal's skeleton. |

|

Still looking but not finding. Plesiosaur skulls tend to be

very rare in the fossil record, in part because of their relatively small size and light

construction. The two bones under the meter stick are probably the scapulas that

help support the front limbs. |

|

Not a good picture, but at least an attempt to show the paddle

bones that laid in a jumbled pile on the west side of the northern most concretion.

(Hint: the bones are hour glass shaped) |

|

A good picture of two of the cervical vertebrae laying near the

middle of the specimen. The one on the left is sitting on its end, while the one one

the right is laying on its side. |

|

Back to concretion #1... now you can see the bone, can't you?

Glenn Storrs found it late in the afternoon after I had missed seeing it that

morning ........... (its the lump coming out on the right hand side of the picture. |

Day 7 (Sunday) This was to be Pam’s and my last day on the dig since I had

to return to work on Monday. The field crew had dwindled to Glenn, Jim, Richard, Steve and

myself, and I felt bad about leaving without finishing the dig. To make matters worse,

Richard and Steve were also leaving and the bulk of the heavy work of removing the

concretions the following week would fall to Glenn and Jim. The day was really nice with a

breeze, heavy clouds and temperatures in the low 60s. When we removed the tarp, we found

that Tony, the Night Watch-Toad (Bufo woodhousii)

was still there and on the job. I never figured out where he went during the hot,

day-time hours, but he was always on the job when we got to the site in the morning.

We worked as quickly as we could to free up the concretions and to locate any

additional bones that were resting beside them. Just before noon, I started taking notes

on the stratigraphy of the site (job’s not done until the paperwork is finished). The

find was conveniently located between a couple of bentonite layers, near the top of the

Sharon Springs member. We would be able to measure downward from the contact with the

overlying Weskan member and have good documentation on the stratigraphic location (and

age) of the plesiosaur. We had lunch and wrapped up our part of the dig about 2:00 PM, and

got on the road for the 5 hour trip back home.

|

Looking to the south at the dig site after all of the smaller

bones had been removed and packed away. The labels on the picture indicate the

general locations of various parts of the plesiosaur. |

|

The stratigraphy of the site looking north from the bottom of the

gully. The surface was defined by large septarian concretions and there were

prominent bentonites about 3 meters above and below the specimen. The specimen was

found about 10 meters below the contact of the Sharon Springs member with the Weskan

member of the Pierre Shale (late Campanian, Zone of Baculites mclearni,

approximately 80 mya). |

|

Another view, looking north at the dig site as it appeared

on Sunday, June 27, showing the extent of the overburden that had to be removed. A

wench was used to pull the jacketed concretions up the slope to the truck. |

|

Pete Bussen shares a few stories as Richard Swigart clears the

shale from the concretion containing most of the shoulder bones of the plesiosaur. |

|

Glenn gets plastered! Although the concretions were very

solid, they were given partial jackets of burlap and plaster to protect the exposed bones

that were inside. Preparation of the remains will be more difficult than usual for

the Pierre Shale because the concretion is harder than the bone. |

|

Enclosing a fossil in a protective jacket of plaster and burlap is

a process that probably dates back to the days of Cope and Marsh. While other

methods have been tried, plaster jackets are still regarded as the most practical in the

field by most paleontologists. |

|

"Okay, guys, now pay attention..... this will be on the

test," says Glenn while Jim Clark and Steve Johnson stay focused on other duties. |

|

Just a little advertisement for the Cincinnati Museum of Natural

History. It has been a real pleasure to work with Glenn Storrs and his crew the last

couple of years. A big Kansas thank you to the volunteers who came all the way from

Cincinnati, and to the Oceans of Kansas crew (Angie, Richard and Steve), who helped with

the dig. |

|

"Hey, put that camera down!" says Mike, "I'm

supposed to be the one taking pictures on this dig!" Too late, but the

photo does show our nifty and very official Cincy-99

Dig T-shirt. |

| Days 8-11 (Monday-Thursday) Glen Storrs and Jim Clark finished up

the dig on Wednesday, June 30, finding a few more bones and most of a complete paddle as

they removed and jacketed the concretions. With the help of Pete Bussen and his vintage Ford tractor the following

morning, they loaded up the specimen into two trailers for the long drive back to

Cincinnati. Jim drove straight back while Glenn dropped by our home for a brief overnight

visit. After a hot meal, a soft bed, and a shower, we sent him on his way with some

home-baked chocolate chip cookies the following morning. Now all we have to wait on is for

the preparators to do their magic with the specimen and show us what we all worked so hard

to obtain. Hopefully, it won’t take a long time to get the plesiosaur into a

presentable form. If you are in the Cincinnati area, be sure and stop by Glenn’s

place downtown (the Cincinnati Museum of Natural

History and Science) and take a look at his collection of Kansas fossils. (Styxosaurus

skull KUVP 1301)>> |

|

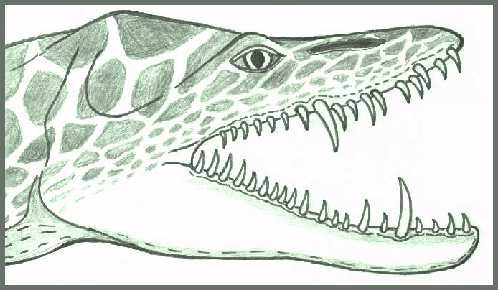

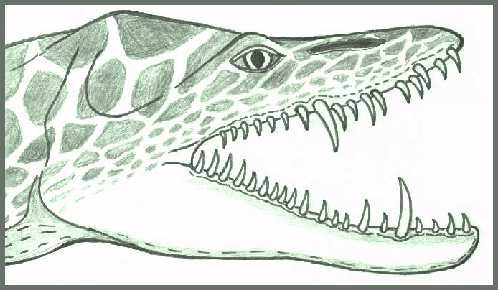

"Styx", the official Oceans of Kansas

Paleontology mascot for the 1999 Cincinnati Museum plesiosaur dig. (From the skull of Styxosaurus snowii in the Museum of Natural History at the University of Kansas,

Copyright © 1999 by Mike Everhart)

FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT

PLESIOSAURS

Kansas plesiosaurs (Updated 2007)

Where the elasmosaurs roam....

Prehistoric Times (#53, April, 2002)

Plesiosaur Stomach Contents- 2001

Plesiosaur Gastroliths -2000

"We Dug Plesiosaurs" - with

the Cincinnati Museum in 1998

Completing the dig with the New Jersey

State Museum -1992

On a Plesiosaur dig with The New Jersey

State Museum -1991

A webpage about Plesiosaurs

(Elasmosaurs)

A webpage about Pliosaurs (short-necked

plesiosaurs)

Plesiosaur References: A listing of

publications related to plesiosaurs

A list of references in my library about

mosasaurs and plesiosaurs.

Plesiosauria

Translation and Pronunciation Guide

Richard

Forrest's listing of plesiosaur specimens and literature

Also, you

can visit Ray Ancog's Plesiosaur FAQ Page (Frequently Asked Questions)

Reference: Carpenter, Kenneth, 1999, Revision of North

American Elasmosaurs from the Cretaceous of the Western Interior, Paludicola, 2(2):148-173

Credits: The drawing of the plesiosaur at the top of the page was adapted

from Kansas Geology, Rex C. Buchanan, Editor, University Press of Kansas, 1984 and

is used with permission of Rex C. Buchanan. The background image is from a photo of the

mounted specimen of Thalassomedon haningtoni at the Denver Museum of Natural History,

Copyright © 1999 by Mike Everhart.

BACK TO THE OCEANS OF KANSAS PALEONTOLOGY

INDEX PAGE