|

SOMETHING ABOUT PLIOSAURIDS AND

POLYCOTYLIDS

Copyright ©2001-2013 by Mike Everhart

Last revised 11/10/2013

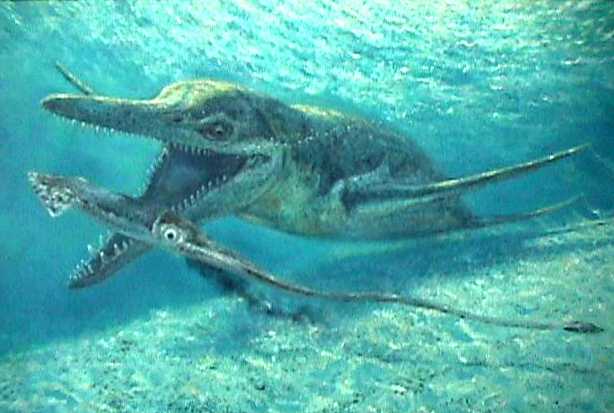

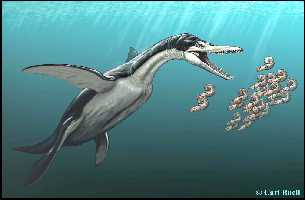

LEFT: "Brachauchenius and squid" -Copyright © Dan Varner; used with permission of

Dan Varner

July 3, 2003 - Translated into French

by Jean-Michel Benoit (Click on flag) |

Pliosaurid or Polycotylid?

Cretaceous plesiosaurs have been traditionally divided into two major

sub-groups; the long-necked, small headed "elasmosaurs" and the short-necked,

larger headed "pliosaurids." For a time, this was convenient for most purposes,

but it has become a somewhat arbitrary method of dividing the group since some of the

so-called "polycotylids" of the Late Cretaceous may be more closely related to

the elasmosaurs. The discussion of the systematics of plesiosaurs, however, is beyond the

scope of this article (see Carpenter 1996; and O'Keefe 2001; 2004, 2008 for a

further information).

On this this webpage, we will consider the pliosaurids to include the

large-headed, short-necked plesiosaurs, such as Kronosaurus and Brachauchenius

lucasi that became extinct about the Middle Turonian stage of the Late

Cretaceous, along with the polycotylid Trinacromerum bentonianum. Three

polycotylids, Polycotylus latipinnis, Dolichorhynchops osborni and D.

bonneri, lived during the latter part of the Late Cretaceous in the Western Interior

Sea

For information about plesiosaurs in general, and especially the long necked

variety, see the Something About Plesiosaurs webpage. Click

here for the latest information on Elasmosaurus platyurus.

For other Oceans of Kansas webpages about plesiosaurs, see: On

a dig for the New Jersey State Museum Plesiosaur; Completing

the Dig for the New Jersey State Museum Plesiosaur - 1992; We Dug Plesiosaurs-1998; Cincinnati

Museum Plesiosaur Dig in 1999; and the Styxosaurus snowii

elasmosaur at the South Dakota School of Mines. See also Ben Creisler's Plesiosaur Translation and

Pronunciation Guide for more information on plesiosaur names and their pronunciation.

How did plesiosaurs swim?? .... Consider the possibilities here: PLESIOSAUR SWIMMING --- Animations

on the Plesiosauria website by Adam Stuart Smith

PLIOSAURIDS:

Brachauchenius lucasi

| The only pliosaurid officially recognized from Kansas at

this time is Brachauchenius lucasi Williston 1903. A

few fragmentary specimens suggest one or more other species may have been present. In

Kansas, these short-necked pliosaurids are relatively rare, but are represented by two

excellent specimens, the largest of which is on exhibit at the Sternberg

Museum of Natural History. Also, see the Brachauchenius

webpage for more information. |

SYSTEMATIC PALEONTOLOGY

Order Plesiosauria, de Blainville 1835

Superfamily Plesiosauroidea, Welles 1943

Family Brachaucheniidae Williston 1925

Genus Brachauchenius lucasi Williston 1903 |

|

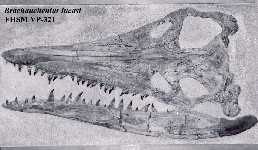

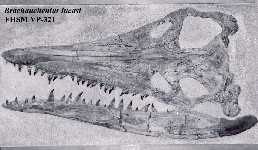

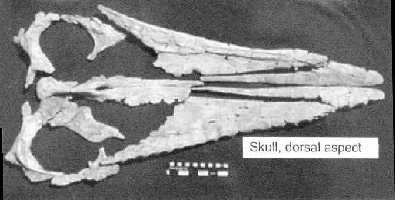

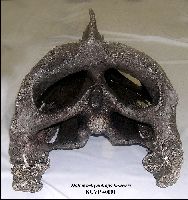

Certainly the largest of the Kansas pliosaurids is Brachauchenius lucasi. The holotype (USNM 4989) was

collected from the "Benton Formation" in Ottawa County, Kansas and was described

by Samuel Williston in 1903. A second specimen (UNSM 2361) was collected from the Eagle

Ford Formation near Austin, Texas, and described by Williston in 1907. The skull of a

third specimen (FHSM VP 321, shown here) is more complete and somewhat better preserved.

It was collected by George Sternberg in October, 1950, from the Fairport Chalk member of

the Carlile Shale, in Russell County, Kansas, and is on display in the Sternberg Museum at

Fort Hays State University. This skull is about five feet (152 cm) in length along the

mid-line, and must have come from a creature that was truly huge. Additional pictures are HERE. |

|

LEFT: The partial skull of a Brachauchenius lucasi (UNSM

50136) specimen from an unknown locality in Kansas. Very similar in size and preservation

to FHSM VP-321 (above). RIGHT: A portion of the skull and a jaw with teeth of a Brachauchenius

lucasi specimen (UNSM 112437) from Mitchell County discovered in the Graneros Shale

during the construction of the Glen Elder Dam. Possibly the oldest known specimen of this

species. (Both specimens in the collection of the University of Nebraska State Museum) |

|

|

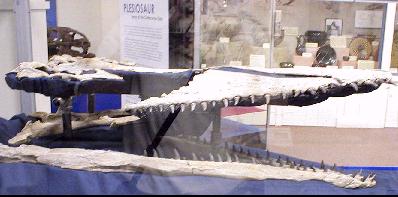

LEFT: Photograph (click to enlarge) of a recently discovered skull

and lower jaws of a Brachauchenius from the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area

in Utah. Skull is slightly less than a meter in length. This picture was part of a poster

presentation by David Gillette and Barry Albright at the 2003 Society of Vertebrate

Paleontology meeting in St. Paul, MN. |

|

LEFT: This a photo of the same Brachauchenius specimen now on

exhibit in the John Wesley Powell Memorial Museum in Page, Arizona. According to

Merle Graffam, who is the co-discoverer of the specimen, there are more than ten separate

finds of pliosaurids in Utah. All are from the Tropic Shale (Upper Cenomanian -

Lower Turonian) and are about 93 million years old. (Photo by Merle Graffam) |

|

LEFT: Here a giant pliosaur (Brachauchenius

lucasi) is about to make lunch of a small turtle similar to Desmatochelys. Brachauchenius was one of the last of the

pliosaurs and made it's final appearance in Kansas during the deposition of the Fairport

Chalk Member (middle Turonian) of the Carlile Shale. Dan Varner © painting courtesy of the Museum of Northern Arizona. |

|

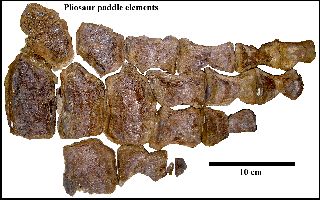

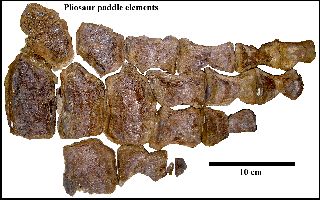

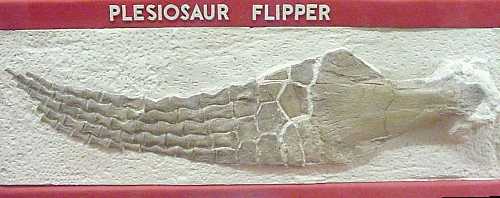

LEFT: A portion of the paddle of a

very large pliosaur (FHSM VP-13997) from the basal Lincoln Limestone Member of the

Greenhorn Limestone (Middle Cenomanian), Russell County, KS. The bones would have

come from a paddle that was about 2 m (6.5 ft) in length, and a Brachauchenius-like

pliosaur that was about 25 feet long. |

|

RIGHT: A large pliosaur tooth

collected from the upper Dakota Sandstone (Mid-Cenomanian) by Keith Ewell in 2004. The

tooth is most likely from Brachauchenius, and if so, would be the earliest report

of this genus anywhere. |

Kronosaurus:

Both Williston (1907) and Carpenter (1996) suggested that Brachauchenius

was closely related to Kronosaurus from the Early Cretaceous of Australia and to

the Jurassic pliosaurid, Liopleurodon.

|

According to local sources in

Australia, Kronosaurus queenslandicus

was discovered by a station owner named Ralph William Haslam Thomas. The remains were dug

up by the Harvard expedition after they were shown where it was on his 20,000 acre

property "Army Downs" near Hughenden in central Queensland, Australia. Mr.

Thomas apparently had known about a row of large vertebrae poking out of the ground for

many years prior to the Harvard expedition. He in turn informed the Harvard team of its

existence. When it was finally dug up, the specimen was shipped to the United States

in 86 cases weighing approximately 6 tons. The export permit states that the specimen was

transported the SS Canadian Constructor about the 1st of December 1932. (Shaw

Studio photograph). Click here for an older black and

white photograph. |

POLYCOTYLIDS:

Shortly after the discovery of Elasmosaurus

platyurus by Dr. Theophilus Turner (Cope, 1868) in Pierre Shale of Logan County,

Kansas, another "new" kind of plesiosaur was found in the upper Smoky Hill Chalk

"about five miles west" of Fort Wallace (Cope, 1871, p. 386). A land agent and

part-time fossil hunter named W. E. Webb, discovered the remains of a much smaller

plesiosaur that Cope (1869) called Polycotylus latipinnis (USNM 27678) from a

pelvic arch and twenty-one vertebrae. The genus name refers to the deep

"cupping" of the anterior and posterior surfaces of the vertebrae, a character

that was quite different from other plesiosaur vertebrae seen by Cope up until then.

Following Webb's discovery, two other species of short necked plesiosaurs were

found in Kansas. One, Trinacromerum, was discovered in the underlying "Fort

Benton" Formation, and was much older than Polycotylus. The other, Dolichorhynchops,

was also found in the Smoky Hill Chalk and lived at the same time as Polycotylus.

Trinacromerum bentonianum

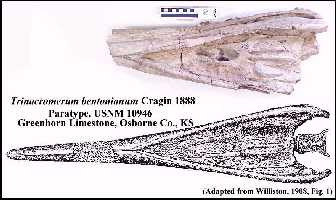

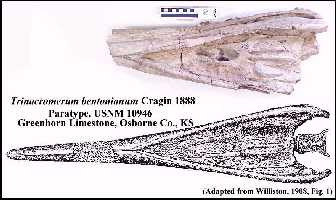

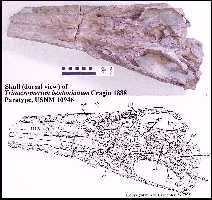

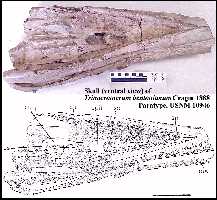

| Trinacromerum bentonianum Cragin 1888 was described from

two skulls (USNM 10945 -holotype and USNM 10946 - paratype) found in the (?) Fencepost

Limestone member of the Greenhorn Limestone (early Middle Turonian) in Osborne

County, Kansas. Carpenter (1996) assigned both Trinacromerum

and Dolichorhynchops to the Polycotylidae. |

SYSTEMATIC PALEONTOLOGY

Order Plesiosauria, de Blainville 1835

Superfamily Plesiosauroidea, Welles 1943

Family Polycotylidae, Cope 1869

Genus Trinacromerum Cragin 1888

Trinacromerum bentonianum Cragin 1888 |

|

The specimen at upper left is the paratype skull (USNM 10946) in

ventral view. The drawing shows it as figured in Williston 1908. I had the opportunity to

photograph it in the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL, during my visit there

in August, 2002. A larger image of Williston's Fig. 1 is HERE. |

|

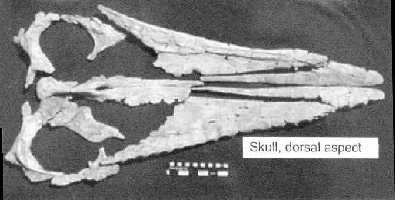

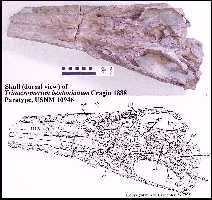

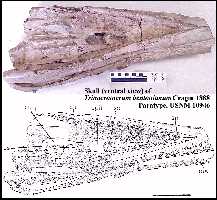

Carpenter (1996) figured the skull of Trinacromerum

bentonianum (USNM 10946 - paratype) in more detail than Williston. These figures are

from an early draft of the 1996 publication and are copyright © by Kenneth Carpenter;

used with permission of Ken Carpenter. LEFT: Dorsal view

RIGHT: Ventral view |

|

|

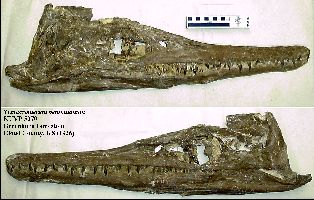

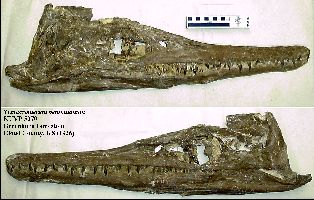

LEFT: A complete, articulated skull of Trinacromerum

bentonianum (KUVP 5070) in right and left lateral views. The specimen was

discovered in December, 1936, during the construction of a road-cut along U.S. 81 Highway,

south of Concordia (Cloud County), Kansas. This specimen was originally described in

1944 by Elmer Riggs and named Trinacromerum willistoni after S. W. Williston.

Per Carpenter (1996), the original name is a junior synonym of T. bentonianum. The

lower jaw measures 74.5 cm (29 inches). RIGHT: The distal end of the

jaws in right lateral view. The specimen consists of a complete skull with

mandible, fifty vertebrae (fifteen cervicals including the atlas-axis), ribs, most of the

pectoral girdle, both pubes and the ischia (Riggs, 1944). |

|

|

LEFT: The back of the skull of Trinacromerum bentonianum

(KUVP 5070) in left lateral view. Riggs (1944) noted that it occurred "10 feet

below the Jetmore Chalk member in beds which, futher west of this area, have been

classified as the Hartland Shale member of the Greenhorn Limestone formation. Carpenter

(1996) reassigned the specimen to T. bentonianum, and Schumacher and Everhart

(2005) reviewed Rigg's locality and stratigraphic information and confirmed the age as

Late Cenomanian. RIGHT: The cranial portion of the skull in right

lateral view (top) and the posterior portion of the skull in right lateral view (lower).

|

|

|

LEFT: Part of the remains of a large Trinacromerum bentonianum

(FHSM VP-698) found by George Dreher in Ellis County, Kansas. The specimen was collected

by George Sternberg and M. V. Walker in June, 1956 from the Blue Hill Shale Member of the

Carlile Shale and is Middle Turonian in age. The specimen consists of a 3 m (10 ft) string

of vertebrae, attached ribs and some limb elements. The axis-atlas vertebrae was included,

but the skull was not found. Sternberg's description of this jacket says; "In the

articulated column, this section fits between section 2 and 3. This section contains

about 21 continuous vertebrae and a number of ribs. The section is about 50" long and

is the widest and largest section in the series. Packages #4 and #5 go with the section,

also some loose rock slabs with rib elements." |

|

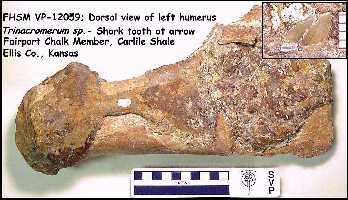

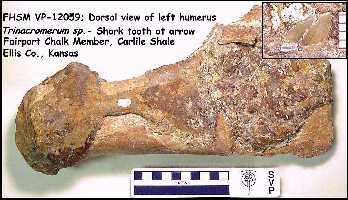

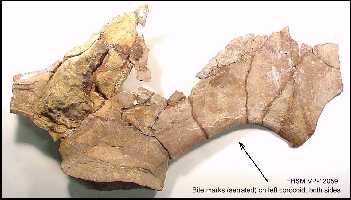

LEFT: A dorsal view of the left humerus of a Trinacromerum

bentonianum (FHSM VP-12059) in the Sternberg Museum collection, with an associated Squalicorax

falcatus tooth (inset). (Another bone here) RIGHT:

Shark bite marks on both sides of the left coracoid of VP-12059. (Fairport Chalk,

Ellis County, KS) |

|

|

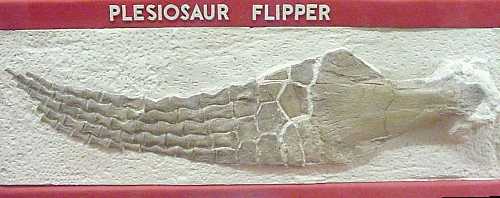

LEFT: The front paddle of another Trinacromerum bentonianum

(ESU 5000) that was found in the 1970s south of Wilson Lake in Russell County. The

locality is at the contact between the Greenhorn Limestone and the Fairport Chalk Member

of the Carlile Shale (early Middle Turonian). The paddle is about 1.1 m (43 in.) long Sadly,

however, the rest of the specimen was stolen from the dig site by unknown persons and was

never recovered. A single surviving paddle is on exhibit in the Johnston Museum of Geology,

Emporia State University, Emporia, Kansas. |

As an interesting side note (to me at least), the last known fossils of Trinacromerum

bentonianum in Kansas occur in the same rocks (Fairport Chalk and Blue Hill Shale

members of the Carlile Shale - Middle Turonian) as the first known remains of mosasaurs.

Polycotylus latipinnis:

| "[Cope] also explained, from specimens, the characters of a

large, new Plesiosauroid from Kansas, discovered by Wm. E. Webb,

of Topeka, which possessed deeply biconcave vertebrae, and anchylosed neural arches, with

the zygapophyses directed after the manner usual among vertebrates. The former was thus

shown to belong to the true Sauropterygia, and not to the Streptosauria, of which

Elasmosaurus was type. Several distal caudals were anchylosed, without chevron bones, and

of depressed form, while proximal caudals had anchylosed diapophyses and distinct chevron

bones. The form was regarded as new, and called Polycotylus latipinnis,

from the great relative stoutness of the paddle." E. D. Cope (1869). |

SYSTEMATIC PALEONTOLOGY

Order Plesiosauria, de Blainville 1835

Superfamily Plesiosauroidea, Welles 1943

Family Polycotylidae, Cope 1869

Genus Polycotylus Cope 1869

Polycotylus latipinnis Cope 1869 |

Polycotylus latipinnis was the second species of plesiosaur found in

Kansas. Cope (1875, p. 70) noted that the remains of the type specimen were found by

William Webb "about 5 miles WEST of Fort Wallace, on the plains near [the] Smoky Hill

River, Kansas, in a yellow Cretaceous limestone." The problem with this locality is

that there are no exposures of Smoky Hill Chalk 5 miles west of Fort Wallace. It is likely

that the locality is 5 miles east of Fort Wallace in the yellow Smoky Hill Chalk near the

Smoky Hill River. According to O'Keefe (2004), the remains consist of

"vertebrae, an ilium, and metapodials at the Smithsonian (USNM 27678) as well as more

vertebrae and assorted phalanges housed at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH

1735). It is uncertain how the remains became divided among the two museums.

|

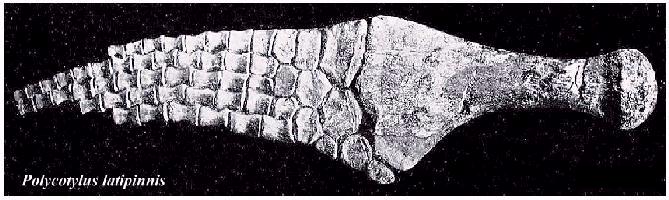

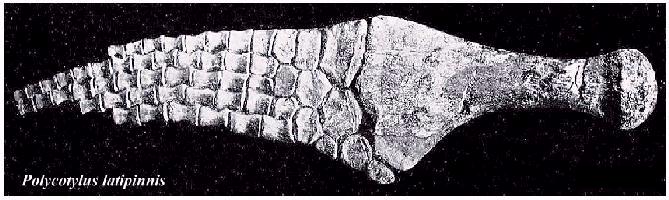

LEFT: A cast of the left rear paddle of Polycotylus latipinnis

(KUVP 40002), part of a nearly complete specimen collected from the Pierre Shale of South

Dakota in the 1970s. |

|

In 1903, Williston wrote "Some years ago, an excellent

specimen of a paddle of a plesiosaur (KUVP 5916) in the exhibit of the University of

Kansas Museum of Natural History) belonging in all probability to Polycotylus

latipinnis Cope was collected by Mr. George R. Allman of Wallace, Kansas, from the

upper Niobrara Chalk of the Smoky Hill River, east of Fort Wallace." Click here for more recent photo |

"The bones of the paddle were, for the most part, found in their natural

relations, but were separated in the collection of them. The radius and ulna of second

paddle, together with some of the smaller bones showed weathering, and doubtless had been

picked up from the surface. It has required but little trouble to fit into their

natural relations all the bones except the most of the phalanges, which, presenting no

lateral surfaces for articulation, could only be located from their other

characters."

Williston (1906, p. 233) noted that the "genus Polycotylus,

described by Cope in 1870 from a number of mutilated vertebrae and fragments of the podial

bones has remained hitherto much of a problem, and its characters have been very generally

misunderstood. Fortunately, there is an excellent specimen in the Yale Museum (No. 1125)

collected many years ago by the late Professor Marsh in the vicinity of Fort Wallace,

Kansas, from the Niobrara chalk, which I believe can be referred with certainty to the

type species P. latipinnis Cope. That it belongs to the genus Polycotylus

is beyond dispute, the vertebrae agreeing quite with the type as they do. This

species seems to be the most common one of the order in the Kansas chalk, and is

represented by several other specimens in the Yale Museum and by several specimens in the

University of Kansas collection."

Williston (1906, p. 234) went on to re-describe the species from what became the

"paratype" specimen - YPM 1125:

"Polycotylus. Teeth rather

slender, with numerous well marked ridges. Face with slender beak. Cervical vertebrae

twenty-six in number; dorsals twenty-eight or twenty-nine, inclusive of three

pectorals; all short and all of nearly uniform length. Chevrons articulating in a

deep concavity; all the vertebrae, and especially the cervicals, rather deeply concave,

and with a broad articular rim. Pectoral girdle with distinct clavicles, interclavicles,

and interclavicular foramen; the scapulae not contiguous in the middle. Coracoid with a

long anterior projection, united in the middle, back of the interglenoid bar, to the

posterior margin; a foramen on each side, back of interglenoid thickening. Ischia

elongated. Paddles with four epipodial bones all much broader than long."

|

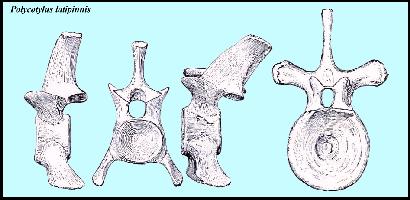

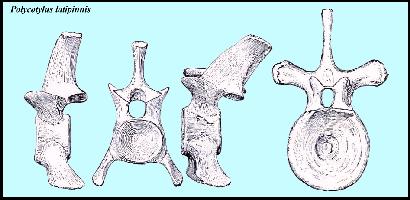

LEFT: Two cervical vertebrae of Polycotylus latipinnis

(YPM 1125) from the side and behind; and a dorsal vertebrae from the front. (Williston

1914, Fig. 34) RIGHT: A probable humerus and femur of Polycotylus

latipinnis (FFHM 1972.126.12f) in the collection of the Fick Fossil and History Museum, Oakley, KS. |

|

|

Dolichorhynchops osborni:

Note that these plesiosaurs were featured in the 2007 National Geographic

IMAX movie "Sea Monsters"

and in my book, "Sea Monsters - Prehistoric Creatures of the Deep." |

| Polycotylus latipinnis and Dolichorhynchops osborni

were the "end of the line" so far as the short-necked polycotylids were

concerned. Polycotylus is known only from fragmentary material, mostly

from the Smoky Hill Chalk, and more recently from Alabama (O'Keefe, 2004). The first two

examples of Dolichorhynchops osborni Williston 1903 were found by George

Sternberg in the Smoky Hill Chalk in Logan County, KS. Dolichorhynchops persists

into the Campanian and possibly the Maastrichtian (See Adams, 1997). A brief description of the skull of

Dolichorhynchops osborni as provided by Williston (1903:14) is repeated here:

"Head elongate, the facial region much attenuated; teeth nearly uniform in size,

small; prefrontal and postfrontal bones not joined; parietals extending into a high crest;

supraoccipital bones separated; internal nares small, included between the vomer and

palatine only; palatines broadly separated throughout; a large vacuity between the

pterygoids anteriorly; quadrate process of pterygoids short." |

SYSTEMATIC PALEONTOLOGY

Order Plesiosauria, de Blainville 1835

Superfamily Plesiosauroidea, Welles 1943

Family Polycotylidae, Cope 1869

Genus Dolichorhynchops Williston 1902

Dolichorhynchops osborni Williston 1902 |

|

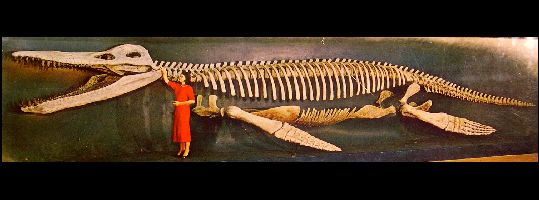

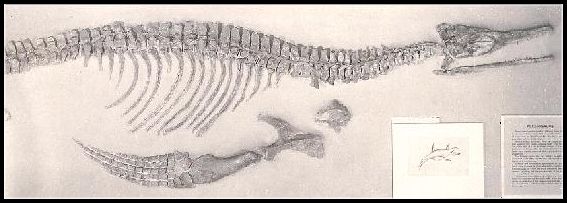

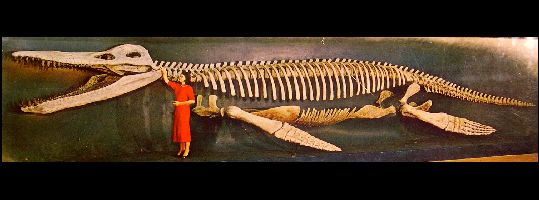

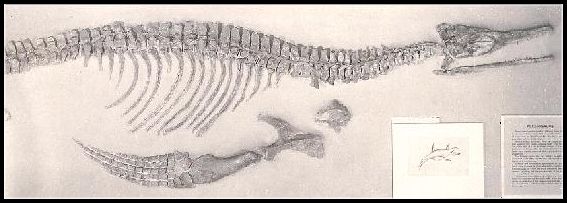

The mounted holotype of Dolichorhynchops osborni (KUVP

1300) at the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History, with a replica of the the

skull. Click for larger version of this picture and

click here for the 1946 version of this exhibit,

showing the original skull of the specimen. |

|

|

LEFT and RIGHT: Several closer views of the holotype specimen at

the University of Kansas. |

|

|

|

|

LEFT and RIGHT: These photos show a drawing published by Williston

(1903) and the skull of the specimen in the KU collection. |

|

|

|

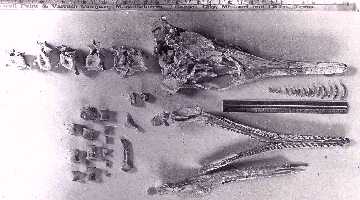

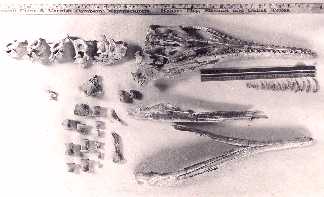

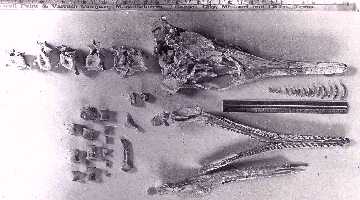

Rare pictures of a juvenile skull of Dolichorhynchops osborni found

by George F. Sternberg in 1926 in the Smoky Hill Chalk of Logan County, Kansas. George

also had the distinction of finding the type specimen (KUVP 1300, above) as a teenager in

1900. See Everhart (2004) for the history of this specimen. Photos by

George F. Sternberg (Smithsonian archives). |

|

|

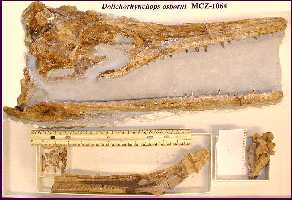

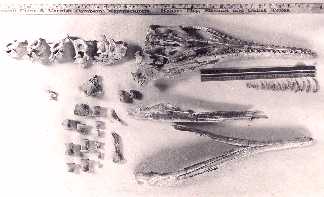

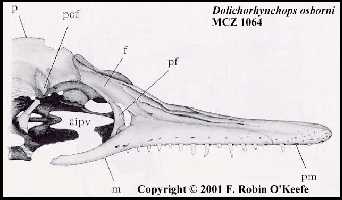

LEFT/ RIGHT: After being offered for sale to the Smithsonian and

the American Museum of Natural History, the specimen was mounted in plaster with just the

right side of the skull showing, and acquired by the Museum of Comparative Zoology

(MCZ) at Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. The specimen was curated as MCZ 1064. Photo by

George F. Sternberg (about 1926) - from the archives of the Sternberg

Museum. |

|

|

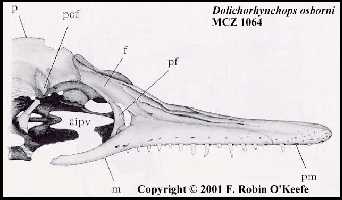

Unfortunately, the plaster mount hides most of the important

details of the skull from view. It was removed from the exhibit in the 1950s. The drawing

at left of the specimen was published recently by F. Robin O'Keefe and is used with

permission. (See: O'Keefe, F. R., 2001. A cladistic analysis and

taxonomic revision of the Plesiosauria (Reptilia: Sauropterygia). Acta Zool. Fennica

213:1-63.)

Also: O'Keefe, F. R. 2004. On the cranial anatomy of the

polycotylid plesiosaurs, including new material of Polycotylus latipinnis Cope,

from Alabama. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 24(2):326-340. |

|

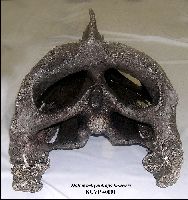

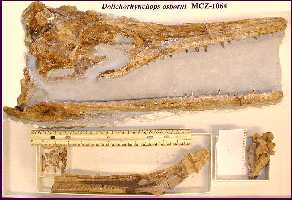

These recent pictures of MCZ-1064 were provided by Charles R.

Schaff, Curatorial Associate of the Museum of

Comparative Zoology and are used with his permission. LEFT: The

right side of the skull, and parts of the lower jaws

RIGHT: This photo shows the elements of the right rear paddle. The femur

is at the lower left, and an ileum (part of the pelvis) is at the upper right. |

|

Everhart, M. J. 2004. New data regarding

the skull of Dolichorhynchops osborni (Plesiosauroidea: Polycotylidae) from

rediscovered photos of the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology specimen. Paludicola

4(3):74-80.

ABSTRACT: The Dolichorhynchops osborni specimen (MCZ 1064) in the Museum of

Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, was the second of only

three nearly complete specimens of this species ever recovered from the Smoky Hill Chalk

Member of the Niobrara Chalk Formation (Upper Cretaceous). The remains were discovered by

George F. Sternberg in 1926 and later acquired by Harvard. Sternberg apparently mounted

the skull in a block of plaster that obscures many important details and limits its

usefulness. Recently re-discovered photos of the skull, included in correspondence sent by

Sternberg to Charles W. Gilmore in 1926, provide an excellent record of the original

appearance of this rare specimen. Measurements taken from these photographs are compared

with those published of other specimens of this species. |

|

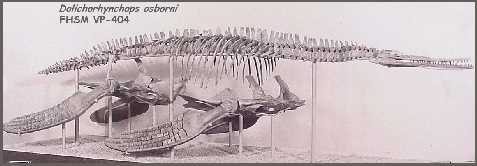

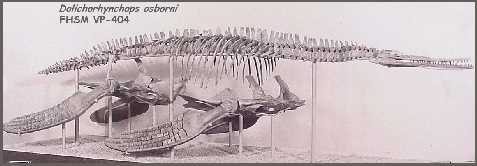

LEFT: A third, nearly complete specimen (FHSM VP 404, shown here

in right lateral view and below in 1960 vintage pictures) was found in Logan County by

Marion Bonner in October, 1955, and is currently on display in the Sternberg

Museum. View from the left side is HERE.

The specimen was described by Marion Bonner's son, Orville, in his 1964 Masters

thesis. See also Sternberg and Walker (1957).

In George F. Sternberg's records, there is a handwritten note that says.

"Plesiosaur Trinacromerum osborni presented 12-12-55 by the collector,

M.C. Bonner and son Orville, Leoti, Kans. to the College Museum." |

|

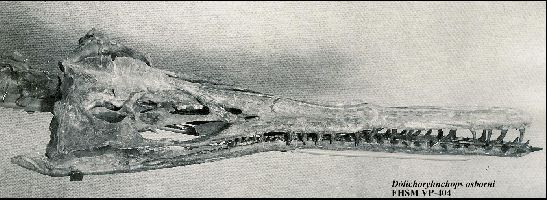

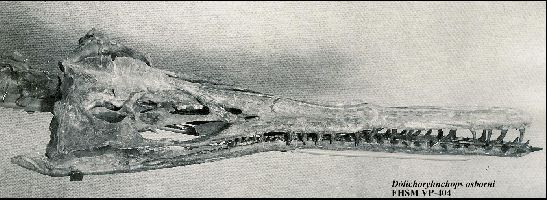

LEFT: A 1950s photo of the skull of Dolichorhynchops

osborni in right lateral view. The skull is long and narrow. It is also lightly

constructed and is almost always found severely crushed. The skull of this specimen in the

Sternberg Museum is about 16 inches long (51.3 cm), and probably came from a fairly young

individual. The skull of a larger individual

(KUVP 40001) found in Wyoming was over 3 feet (98 cm) long. Photo from the Sternberg

Museum of Natural History. NEW (12/2007) -

Detailed photographs of skull. |

|

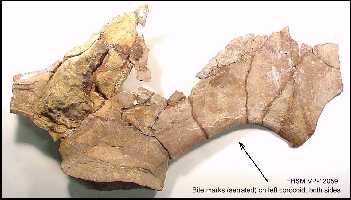

LEFT: This photo shows a left lateral view of the pelvis (pelvic

girdle) and a portion of the posterior dorsal vertebrae of the FHSM VP-404 specimen. Note

that the pelvic girdle is only attached to the vertebral column by two slender shafts of

bone.. the ilia... |

|

Plesiosaur paddles (podials) are composed of five 'fingers' with

as many as fifteen bones per digit. The upper bone of the podial is the humerus (front) or

femur (rear) and the lower limb bones (and wrist or ankle) are greatly reduced in number

and function. These elements were held tightly together to form a rigid, wing shaped

paddle or 'airfoil'. By moving these paddles in a coordinated 'figure-eight' pattern, the

animal was more or less able to 'fly' swiftly though the water, much like a modern

penguin, in pursuit of it's prey. |

Below are two sets of drawings of polycotylid skulls from the

draft of a paper by Kenneth Carpenter (Denver Museum of Natural History)......"A

Review of Some Short Necked Plesiosaurs from the Cretaceous of North America". These

drawings are copyright © by Kenneth Carpenter, and used with the permission of Kenneth

Carpenter.

|

Left lateral view of the skull of Dolichorhynchops osborni

(FHSM VP 404) in the Sternberg Museum, Fort Hays State University, Hays, KS. Click on

picture to see a dorsal and ventral view of the skull, and a dorsal view of the mandible

(110 kb .jpg file). Scale = 10cm. Copyright © by Kenneth Carpenter. NEW (12/2007) - Detailed photographs of skull. |

|

LEFT: A left latero-dorsal view of the skull of a juvenile Dolichorhynchops

osborni (UCM 35059) at the University of Colorado Museum at Boulder, CO. Click

on skull to see dorsal and ventral views (84 kb .jpg file). Scale = 10 cm. Copyright © by

Kenneth Carpenter. The specimen consists of a partial skeleton of a

young individual from the Sharon Springs member of the Pierre Shale in Niobrara County,

Wyoming, and provides the most complete skull of a juvenile member of this species. |

When I visited the Field Museum in Chicago in 2002, I photographed

another specimen of Dolichorhynchops osborni (UNSM 50133) that was on loan from

the University of Nebraska State Museum. The pictures below show the top of the skull and

the back of the skull. A close-up of the anterior portion

of the jaws is shown here

Two of the largest polycotylid specimens known from the Western Interior Sea

(KUVP 40001 and 40002) were collected in the Sharon Springs Member of the Pierre Shale in

South Dakota and Wyoming. KUVP 40002 is a nearly complete skeleton, lacking most of the

skull.

|

LEFT: A left lateral view of the reconstructed skull of Dolichorhynchops

bonneri (KUVP 40001) from the Pierre Shale of South Dakota. The new species was

described by O'Keefe in 2008. RIGHT: The same skull in posterior view.

SEE MORE ABOUT THIS SPECIMEN HERE |

|

|

LEFT: An oblique, left posterio-lateral view of the reconstructed

skull (KUVP 40001). RIGHT: The skull as mounted on the reconstructed

skeleton of Dolichorhynchops bonneri in the Rocky Mountain Dinosaur Research

Center. |

|

|

LEFT: One of the two

polycotylid propodials (USNM 9468) recovered from inside the rib cage of a Tylosaurus

proriger from the chalk of Logan County, Kansas (either a humerus or femur) by Charles

Sternberg and sons. Note partially digested appearance. See Everhart, M. J. 2003.

RIGHT: The second of two propodials

recovered by Sternberg, even more severely damaged by stomach acids.

FOR MORE ABOUT THIS SPECIMEN, CLICK HERE

Note that the discovery of this

specimen was the focus of the 2007 National Geographic IMAX film - Sea Monsters |

|

|

LEFT: The femur (16 in / 40 cm long) of a very large Dolichorhynchops

osborni that was collected in 1992 from a concretion near the top of the Sharon

Springs Member of the Pierre Shale in Logan County. My wife, Pam, discovered this

specimen while the rest of us were working on the New Jersey State Museum Styxosaurus snowii. She had asked our friend, Pete Bussen, "What does a plesiosaur fossil look

like in the shale?" They walked up the hill for a look, and within ten minutes,

she picked up a small, sun-bleached paddle bone. She

had found her first plesiosaur. It was coming out of a large septarian concretion near the

top of the Sharon Springs Member of the Pierre Shale. Of course, finding was the easy

part; getting it out the concretion was a lot more difficult (and is the source of my

'flying shovel' story). |

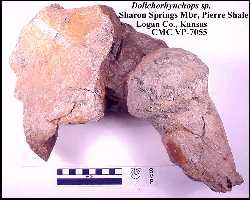

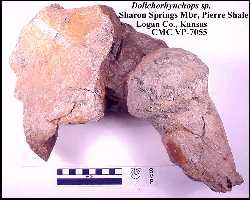

Unfortunately, the concretion had shattered most of the bones and made a

difficult puzzle out of the specimen. It is incomplete and will never be an exhibit

specimen, but it is certainly an excellent example of how big these marine reptiles could

be. Ken Carpenter (Denver Museum of

Nature and Science) identified the remains for me in 1994. In 1999, we donated the

specimen (CMC VP-7055) to the Cincinnati Museum Center. I had the opportunity to take

these pictures in February, 2003.

|

LEFT: This photo shows the nearly round head of an upper limb bone

(femur) and part of the hip, still held together by the matrix of the concretion. RIGHT: Centra of five caudal (tail) vertebrae. |

|

|

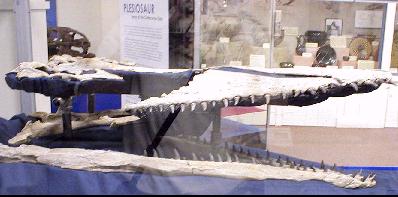

LEFT: A recent picture of the long, toothy skull of FHSM VP-404

on exhibit in the Sternberg Museum of Natural History. This plesiosaur was

definitely a fish-eater. (Age is Early Campanian) RIGHT: A skeletal

reconstruction of Dolichorhynchops osborni in the ancient seas exhibit at the

Smithsonian Institution (USNM V-419645). The specimen was collected in 1977 from Bearpaw

Shale the Custer Battlefield National Park in Montana. (Age is Campanian) |

|

|

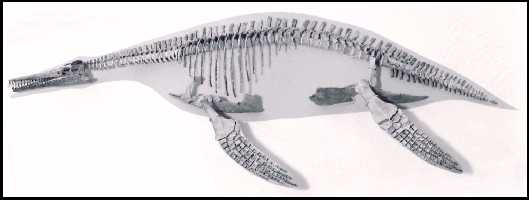

LEFT: This composite skeleton of Dolichorhynchops

osborni is one of the exhibits in the Vienna Museum of Natural History in Vienna

Austria. It was assembled from various sets of partial remains found in the chalk of

western Kansas. The skull is a replica. |

OTHER PLESIOSAUR REMAINS:

Unfortunately, plesiosaurs are few and far between in the Smoky

Hill chalk. What we do find occasionally are the scattered pieces

of plesiosaur carcasses that had been torn apart during scavenging by other predators. The

bones are unusually solid and heavy, but some still bear the marks of the teeth that

severed them from the plesiosaur's body.

|

An 'as found' view of a lonely, sub-adult plesiosaur propodial (LACMNH 148920) eroding out on the surface of

the Smoky Hill chalk in Gove County, Kansas. From the serrated bite marks that were found

on the bone and the fact that no other plesiosaur material was found in the vicinity, it

seems apparent that this readily 'detachable' piece was torn away by scavenging sharks

before (Squalicorax) being dropped to the sea bottom. (See

Everhart, 2003) |

|

Another 'detached' plesiosaur podial (length about 24 inches).

This specimen is on exhibit in the Fick Fossil and

History Museum in Oakley, Kansas. The deep bite marks on the upper portion of the bone

attest to the violence of the scavenging and the size of the scavenger (a large Late

Cretaceous shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli). See

Everhart (2005). |

|

This specimen represents the only plesiosaur skull (FHSM VP-13966) remains that we have ever found

in the chalk (Late Coniacian - about 86 mya). The bone fragments were scattered over a

large area and are mostly unrecognizable. They remained unidentified until we showed them

to J.D. Stewart of the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History. The two semi-circular

shapes are the hinge points for the lower jaw of the plesiosaur, indicating another

possible 'detachable' part that was carried off by a shark. (See

Everhart, 2003) |

|

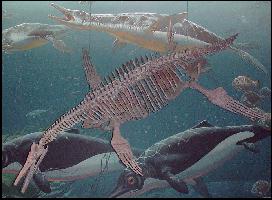

A mosasaur's worst nightmare....when the hunter becomes the

hunted. A Brachauchenius-sized pliosaurid attacks a much smaller

mosasaur....not much of a fight. This encounter could only have occurred during the

Turonian, about 90 mya, because that was the only time that big pliosaurids and mosasaurs

lived together in the Western Interior Sea. This image is copyright © by Dan Varner, and

may not be used in any form without his written permission. |

|

An upper limb bone or propodial of a young plesiosaur (species

indeterminate) found in the Bluffport Marl Member of the Demopolis Formation (Campanian)

in Clay County, Mississippi by Lynn Harrell, Jr. Length is about 8 inches / 20.5 cm.

In juvenile plesiosaurs, the limb bones were growing rapidly and the joints were composed

primarily of cartilage. Note the lack of articular surfaces on the ends of this bone

compared to some of the adult limb bones shown above. |

|

This a picture of the upper half of a partially digested, juvenile

plesiosaur propodial (FHSM VP-139632) which

was found near the base of the Smoky Hill Chalk (Late Coniacian) in Ellis County, Kansas

by the author in 1988. Unfortunately, the rest of the bone (and the animal itself) was no

where to be found. While plesiosaurs in general are not well documented from the lower

Smoky Hill Chalk, there are occasional remains that show they were there in small numbers.

(See Everhart, 2003), and that they were scavenged by sharks. |

|

The Tate Museum in Casper, Wyoming, has a copy of a nearly

complete paddle from a what must have been a huge Jurassic pliosaurid (Megalneusaurus

rex). It was one of the largest marine predators that ever lived. Found

about 1898 by W. C. Knight (University of Wyoming) in Natrona County, Wyoming, this pliosaurid may have been 40 feet long and weighed as

much as 10 tons. The articulated paddle measures 7.25 feet (2.209 m). |

|

|

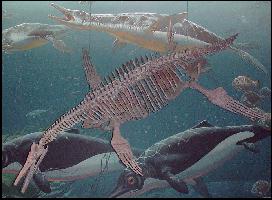

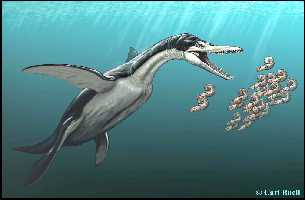

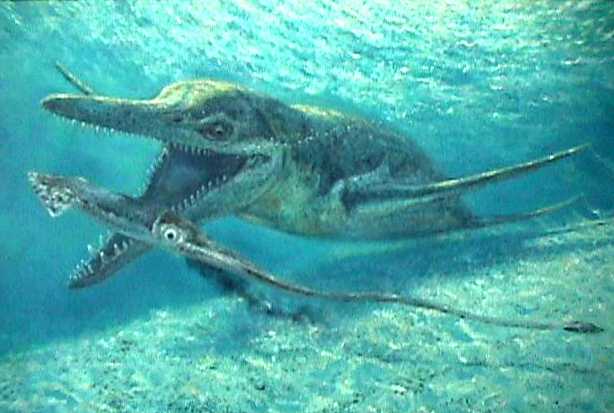

Trinacromerum bentonianum was an earlier Cretaceous

polycotylid that lived in the Western Interior Sea during Cenomanian - Turonian

time. It was quite similar in size and shape to Dolichorhynchops.

LEFT: Paleo-life art by Carl Buell. Copyright © by, and used

with the permission of Carl Buell. The original version of this picture was done by Carl

for Discover Magazine for a story done on this article: Sato, T. and K. Tanabe, 1998.

Cretaceous plesiosaurs ate ammonites, Nature, 394:629-630. Also,

polycotylid artwork by Peter Von Sholly, Russell Hawley, Doug

Henderson, Dan Varner and S. W. Williston. All are copyright © by the

respective artist and may not be reproduced without permission of the artist and Oceans of

Kansas Paleontology. |

--------------------------

The following comments about 'pliosaurids' and their possible

origin was written by Darren Naish and is reprinted here with his permission.

'Pliosaur' is an ambiguous term that, in the past, has been

applied to any plesiosaur with a shortish neck and large head. One group of such animals,

the mid-->Upper Cretaceous polycotylids, are very distinct from other 'pliosaurs' and

are almost certainly related to elasmosaurids (Bakker 1993 and Carpenter 1995, 1997). True

pliosaurids, in contrast, are primitive in the plesiosaur family tree as testified by

their complete set of mandibular bones, and out-group to all other plesiosaurs (clade

Plesiosauroidea). Pliosaurids first appear in the very earliest Jurassic (Hettangian) at

Dorset with Eurycleidus and other indeterminate taxa but did not (as far as is presently

known) make it as far as the late Upper Cretaceous (polycotylids made it to the end). The

term 'pliosaur' should not be used as it refers to an ecotype and not a clade.

Plesiosaurs represent a derived clade in the Sauropterygia Owen,

1860. This group contains a Triassic radiation of amphibious - marine forms long lumped

together as a paraphyletic 'Nothosauria' but now consisting of discrete clades that became

less land-dependent and more derived in style of paraxial locomotion (i.e. they grade up

to the flight of plesiosaurs). Glen Storrs recognizes the most derived 'nothosaurs' (Nothosaurus,

Pistosaurus and relatives) as forming the clade Nothosauriformes with the

plesiosaurs. Basal- and non-nothosauriforms are predominantly Tethyan in distribution and

the presence of the pachypleurosaurs - a clade of lizard-shaped amphibious, small-bodied

reptiles - here too suggests that this is the sauropterygian home. Pachypleurosaurs have

traditionally been regarded as 'nothosaurs' too but they are increasing regarded as a

sauropterygian out-group. Whatever, they are primitive members of the group that includes

plesiosaurs.

Placodonts are a problem. Rieppel and Storrs have them as true

sauropterygians, but this is mildly controversial. The most comprehensive and current view

of placodont relationships is a paper by Mazin in Geobios. It's in French and I

haven't understood it all yet. Cladistic analysis of sauropterygian and placodont

characters by Rieppel did nest Placodontia within Sauropterygia. If this view does not

become accepted, perhaps resurrection of a Euryapsida (Placodontia + Sauropterygia) will

do.

These reptiles are modified diapsids and may be neodiapsids up

there in the younginiform-sauria crown group. I'm unaware of any derived characters that

link sauropterygians (incl. placodonts) with either younginiforms or lepidosaurian

saurians (cases have been made for both alternatives). On the other hand, perhaps the

nearest relatives to sauropterygians are araescelidians (incl. Petrolacosaurus) in which

case they are basal diapsids and not neodiapsids. The description in recent years of a

(probable) marine araescelidian with swimming adaptations, Spinoequalis, implies

that this relationship is a possibility.

The full text of this comment is available at the Archives of the

DINOSAUR mailing list, June 9, 1997.

|

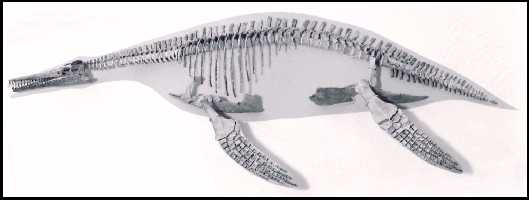

Skeletal drawing of the polycotylid, Dolichorhynchops

osborni (Adapted from Buchanan, 1984, based on KUVP 1300)

|

For more information on Jurassic plesiosaurs: Adam

Smith's The Plesiosaur Directory

REFERENCES:

Adams, D. A. 1977. Trinacromerum bonneri, a new

polycotylid plesiosaur from the Pierre Shale of South Dakota and Wyoming.

Unpublished Masters thesis, University of Kansas, 97 pages.

Adams, D. A. 1997. Trinacromerum bonneri, new species,

last and fastest pliosaur of the Western Interior Seaway. Texas Journal of Science,

49(3):179-198. (See O'Keefe, F. R. 2008)

Bonner, O. W. 1964. An osteological study of Nyctosaurus

and Trinacromerum with a description of a new species of Nyctosaurus,

Unpub. Masters Thesis, Fort Hays State University, 63 pages.

Carpenter, K. 1996. A Review of short-necked plesiosaurs from the

Cretaceous of the western interior, North America, Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und

Paläeontologie Abhandlungen, (Stuttgart) 201(2):259-287.

Carpenter, K. 1997. Comparative cranial anatomy of two North American Cretaceous

plesiosaurs, pp. 191-216, In Calloway, J. M. and E. L. Nicholls, (eds.), Ancient

Marine Reptiles, Academic Press.

Cicimurri, D. J. and M. J. Everhart. 2001. An elasmosaur with stomach contents and

gastroliths from the Pierre Shale (late Cretaceous) of Kansas. Kansas Academy of

Science, Transactions 104(3-4):129-143.

Cope, E. D. 1869. [Remarks on fossil reptiles, Clidastes

propython, Polycotylus latipinnis, Ornithotarsus immanis.]. Proceedings

of the American Philosophical Society xi p. 117. (meeting of June 18, 1869)

Cope, E. D. 1870. Remarks on fossil

reptiles from the Cretaceous of Kansas. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural

Sciences of Philadelphia, p. 132. (Polycotylus latipinnis)

Cope, E. D. 1875. The Vertebrata of the Cretaceous formations of the West.

Report, U. S. Geological Survey Territories (Hayden). 2:302 p, 57 pls.

Cragin, F. W. 1888. Preliminary description of a new or little known saurian

from the Benton of Kansas, American Geologist 2:404-407.

Druckenmiller, P. S. 1998. Osteology and relationships of

a plesiosaur (Sauropterygia) from the Thermopolis Shale (Lower Cretaceous) of Montana. Unpublished Masters Thesis, Montana State University.

Everhart, M. J. 2000. Gastroliths

associated with plesiosaur remains in the Sharon Springs Member of the Pierre Shale (late

Cretaceous), Western Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 103(1-2):58-69.

Everhart, M. J. 2003. First records of

plesiosaur remains in the lower Smoky Hill Chalk Member (Upper Coniacian) of the

Niobrara Formation in western Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions

106(3-4):139-148.

Everhart, M. J. 2004. Plesiosaurs as the food

of mosasaurs; new data on the stomach contents of a Tylosaurus proriger (Squamata;

Mosasauridae) from the Niobrara Formation of western Kansas. The Mosasaur 7:41-46.

Everhart, M. J. 2004. New data regarding the skull of Dolichorhynchops

osborni (Plesiosauroidea: Polycotylidae) from rediscovered photos of the Harvard

Museum of Comparative Zoology specimen. Paludicola 4(3):74-80.

Everhart, M. J. 2005. Bite marks on an elasmosaur (Sauropterygia;

Plesiosauria) paddle from the Niobrara Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) as probable evidence of

feeding by the lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli. PalArch, Vertebrate

paleontology 2(2): 14-24.

Everhart, M. J. 2005. Oceans of Kansas - A Natural History of the Western Interior

Sea. Indiana University Press, 320 pp.

ISBN: 0253345472

Everhart, M. J. 2007. Sea

Monsters: Prehistoric Creatures of the Deep. National Geographic, 192 p.

ISBN-13: 978-1426200854

Everhart, M. J. 2007. Historical note

on the 1884 discovery of Brachauchenius lucasi (Plesiosauria; Pliosauridae) in

Ottawa County, Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions

110(3-4):255-258.

Everhart,

M.J. 2009. Probable plesiosaur remains from the Blue Hill Shale (Carlile Formation; Middle

Turonian) of north central Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions

112(3/4):215-221.

Knight, W. C. 1898. Some new Jurassic

vertebrates from Wyoming. Amer. Jour. Sci., ser. 4, 5(29):378-380. [Megalneusaurus

rex, a giant pliosaurid]

Lingham-Soliar, T. 2000. Plesiosaur locomotion: Is the four-wing

problem real or merely an atheoretical exercise? Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und

Paläeontologie Abhandlungen, (Stuttgart) 217:45-87.

Lucas, F. A. 1903. A new

plesiosaur. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 45:96, pl. XXVIII (Quarterly Issue Vol.

1), 1457.

Lucas, S. G. 1994. Late Cretaceous pliosaurs (Eurapsida:

Plesiosauroida) from the Black Mesa Basin, Arizona, U. S. A. Journal of the Arizona-Nevada

Academy of Science 28(1/2):41-45.

Martin, J. E. and L. E. Kennedy. 1988. A plesiosaur from the late

Cretaceous (Campanian) Pierre Shale of South Dakota: A preliminary report, Proc. S.D.

Acad. Sci., 67:76-79.

Martin, J. E. and A. J. Kihm. 1988. Two unusual stratigraphic occurrences of plesiosaurs

from late Cretaceous formations of the Black Hills area, Wyoming and South Dakota. Proc.

S.D. Acad. Sci., 67:73-75.

Moodie, R. L. 1911. An embryonic plesiosaurian propodial, Trans.

Kansas Acad. Sci. 23:95-101, 9 figs, 1 pl.

O'Keefe, F. R. 1999. Phylogeny and convergence in the Plesiosauria. Journ.

Vert. Paleon. 19(3):67A. (abstract)

O'Keefe, F. R. 2001. A cladistic analysis and taxonomic revision

of the Plesiosauria (Reptilia: Sauropterygia). Acta Zool. Fennica 213:1-63.

O'Keefe, F. R. 2001. Ecomorphology of plesiosaur flipper

geometry. J. Evol. Biol. 14:987-991.

O'Keefe, F. R. 2002. The evolution of plesiosaur and pliosaur

morphotypes in the Plesiosauria (Reptilia: Sauropterygia). Paleobiology 28(1):101-112.

O'Keefe, F. R. 2004. On the cranial anatomy of the polycotylid

plesiosaurs, including new material of Polycotylus latipinnis Cope, from Alabama.

Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 24(2):326-340.

O'Keefe,

F. R. 2008. Cranial anatomy and taxonomy of Dolichorhynchops

bonneri new combination, a polycotylid plesiosaur from the Pierre Shale of Wyoming

and South Dakota. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology

28(3):664–676.

O’Keefe, F.R. and

Chiappe, L.M. 2011. Viviparity and K-selected life history in a Mesozoic marine

plesiosaur (Reptilia, Sauropterygia). Science 333(6044):870-873.

Riess, J. and E. Frey. 1991. The evolution of underwater flight

and the locomotion of plesiosaurs. pp. 131-144, In Rayner, J. M. V. and R.

J. Wooton (eds.), Biomechanics in evolution. Cambridge Univ. Press.

Riggs, E. S. 1944. A new polycotylid plesiosaur. University of

Kansas Science Bulletin 30:77-87.

Robinson, J. A. 1975. The locomotion of plesiosaurs, N. Jb. Geol. Paläont. Abh., 149,

3:286-332.

Russell, D. A. 1967. Cretaceous vertebrates from the Anderson

River N. W. T. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 4:21-38.

Russell, L. S. 1935. A plesiosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of

Manitoba. Jour. Paleon. 9:385-389.

Sato, T. and K. Tanabe. 1998. Cretaceous plesiosaurs ate

ammonites, Nature, 394:629-630.

Schmeisser,

R.L. and Gillette, D.D. 2009. Unusual occurrence

of gastroliths in a polycotylid plesiosaur from the Upper Cretaceous Tropic Shale,

southern Utah. PALAIOS 2009 24: 453-459.

Schultze, H.-P., L. Hunt, J. Chorn and A.M. Neuner. 1985. Type and

figured specimens of fossil vertebrates in the collection of the University of Kansas

Museum of Natural History, Part II. Fossil Amphibians and Reptiles. Miscellaneous

Publications of the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History 77:66 pp.

Schumacher, B. A. and M. J. Everhart. 2004. A new assessment of

plesiosaurs from the old Fort Benton Group, Central Kansas. Joint Annual Meeting of the

Kansas and Missouri Academies of Science, p. 50.

Schumacher, B.A. and M.J. Everhart. 2005. A stratigraphic and

taxonomic review of plesiosaurs from the old “Fort Benton Group” of central

Kansas: A new assessment of old records. Paludicola 5(2):33-54.

Schumacher, B. A. and J. E. Martin. 1995. Polycotylus

sp.: A short-necked plesiosaur from the Niobrara Formation (Upper Cretaceous) of South

Dakota. Jour. Vert. Paleon. 15(suppl. to 3):52A.

Sternberg, G. F. and M. V. Walker. 1957. Report on a plesiosaur skeleton from western Kansas. Kansas

Academy of Science, Transactions, 60(1):86-87.

Tarsitano, S. and J. Riess. 1982. Plesiosaur locomotion -

underwater flight versus rowing. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläeontologie

Abhandlungen, (Stuttgart) 164:188-192.

Tarsitano, S. and J. Riess. 1982. Considerations concerning plesiosaur locomotion. Neues

Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläeontologie Abhandlungen, (Stuttgart) 164:193-194.

Thurmond, J. T. 1968. A new polycotylid plesiosaur from the Lake

Waco Formation (Cenomanian) of Texas. Journal of Paleontology 42:1289-1296.

Williston, S. W. 1902. Restoration of Dolichorhynchops osborni,

a new Cretaceous plesiosaur, Kansas University Science Bulletin, 1(9):241-244, 1 plate.

Williston, S. W. 1903. North American

plesiosaurs, Field Columbian Museum, Pub. 73, Geological Series, 2(1):1-79, 29 plates.

Williston, S. W. 1906. North American plesiosaurs: Elasmosaurus,

Cimoliasaurus, and Polycotylus, American Journal of Science,

series 4, 21(123):221-234, 4 pl.

Williston, S. W. 1907. The skull of Brachauchenius, with special observations on

the relationships of the plesiosaurs. United States National Museum Proceedings

32:477-489. pls. 34-37.

Williston, S. W. 1908. North American plesiosaurs: Trinacromerum. Journal of

Geology 16:715-735. figs. 1-15.

Williston, S. W. 1914. Water reptiles of the past and present. Chicago Univ. Press. 251 pp

Other Plesiosaur information on the Internet:

KANSAS PLESIOSAURS

Barry Kazmer's Plesiosaur Paleontology:

Barry is digging plesiosaur remains from a quarry in southeastern South Dakota.

Plesiosaur References: A listing of

publications related to plesiosaurs from Barry Kazmer's Plesiosaur Paleontology web site.

Australian

Mesozoic Marine Reptiles Dann Pigdon's page about plesiosaurs, pliosaurs and

ichthyosaurs from Down Under.

Plesiosauria

Translation and Pronunciation Guide - An excellent reference by Ben Creisler

Giant

pliosaurs -- real and imaginary - A reality check on pliosaurids by Ben Creisler

Also,

you can visit Ray Ancog's Plesiosaur FAQ Page (Frequently Asked Questions)

Richard Forrest's listing

of plesiosaur specimens and literature - The Plesiosaur Site

Richard

Forrest's 5 Questions about Plesiosaurs (serious stuff!)

The Denver Museum elasmosaur (Thalassomedon

haningtoni)

"The longest neck in the

ocean" (University of Nebraska State Museum elasmosaurs)

A primer on the anatomy of the

plesiosaur skull.

Large gastroliths from a Kansas

elasmosaur.

Plesiosaur stomach contents and

gastroliths

Ben Creisler's Plesiosaur Translation and

Pronunciation Guide

Adam Stuart Smith's

Sea Saur Page

BACK TO THE INDEX

![]()